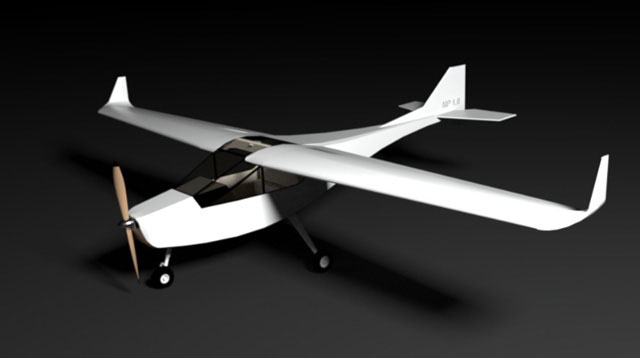

MakerPlane, a thus far nonprofit group founded by John Nicol, is refining an LSA design that will be made available free online. Photo courtesy John Nicol/MakerPlane.

Building an airplane from a kit takes dedication, and, usually, thousands of hours of labor. More often than not, kits and scratch-built efforts are left unfinished by exhausted aviators.

John Nicol hopes to change that, using new technologies for fabricating parts, and “open source” plans that his organization plans to post for free online.

Faster, slimmer, cheaper

By Sarah Brown

If your only exposure to it was watching a MakerBot machine print a copy of comedian Stephen Colbert’s head in 2011, you might be tempted to relegate additive manufacturing—commonly referred to as 3-D printing—to the realm of commodity. But large aerospace companies such as Boeing and EADS Aerospace are taking the technology seriously.

In fact, 3-D printing is making inroads in fields from electronics to aerospace. The process, which involves depositing layers of material to build a component instead of creating it from a mold or machining it from a larger piece of raw material, enables quick prototyping, less material waste, and small-scale production at low cost.

Boeing’s Rapid Prototyping & Modeling Lab in Seattle uses additive manufacturing to produce conceptual and wind-tunnel models, prototype parts, and tools; EADS Innovation Works calls the technology a “game changer,” producing “negligible levels of waste in comparison to traditional machining processes, in which up to 90% of the material is removed.”

The process also allows optimized designs that are not driven by the manufacturing process: EADS Innovation Works said it has used additive manufacturing to produce an air intake baffle for a small aircraft flown in competitive air races. The component replaced an aerodynamically inefficient wire mesh baffle with one incorporating staggered vanes and using “a geometry that was difficult—if not impossible—to manufacture by any other means.” The baffle went from CAD specifications to a ready-to-install component in five days, EADS said.

Nicol founded MakerPlane with a vision of making amateur-built aviation more accessible, and faster, if not cheaper, using a combination of computer numerical control (CNC) machine tools and a new generation of three-dimensional printers, devices that can transform plastic and other raw materials into finished parts. Nonstructural parts, that is. No one plans to print wings in the foreseeable future.

“No, we’re not going to be printing up the (entire) aircraft using a 3-D printer,” Nicol said, dashing hopes raised by a few enthusiastic bloggers.

The new technology would allow builders to make customized parts such as throttle knobs or sun visors, altering the design to suit specific needs. Three dimensional printing is part of that strategy, and would also allow builders to make custom tools on demand, such as clamps, jigs—even a spool of solder.

The concept is not as farfetched as some might think: Three dimensional “printers” are already on the market that cost $1,000, though builders may want to invest in somewhat more expensive units capable of 50-micron resolution. Nicol said there are also various places that make the equipment available on a per-job basis, allowing users to upload digital drawings and have the part or parts shipped anywhere in the world.

“It’s basically just in time manufacture, and it’s manufacturing of your own kit parts,” Nicol said. “What it allows you to do is have control over those parts. If you’ve got the equipment, of course, it makes it a lot easier.”

Nicol, a native of New Zealand now living in Canada, has a military aviation and aeronautical design background, having recently left Lockheed Martin to launch what is so far a nonprofit enterprise. He is collaborating with other professionals including Israeli aircraft designer Jeffrey Meyer, who is taking the lead role developing an open source light sport aircraft design—the first of what they hope will be many digital designs made available free online.

They are far from alone in exploring the potential of three-dimensional printing and automated manufacturing processes. A research team that includes Kendra Short of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, along with partners from Xerox PARC and Boeing, recently landed a $500,000 NASA grant to continue exploration of the potential for three-dimensional printers to make spacecraft. That team envisions a wide range of applications, including tiny craft that can spread through an atmosphere like confetti, or penetrate a planet’s surface with radar. Following an initial study funded by a $100,000 grant, “What we have determined is that there is a broader landscape of realistic possibilities than we had imagined,” Short’s team wrote in their most recent application.

Nicol hopes to transform MakerPlane into a for-profit enterprise, making money from the sale of kits and parts to those who opt not to fabricate their own. (Digital designs and other resources would still be made available at no charge.) The organization is also creating tools that will help builders to collaborate online.

“I’m hoping that MakerPlane might be synonymous with open source aviation,” Nicol said. “We are doing open-source avionics as well.”

Nicol displayed a scale model of the LSA design at EAA AirVenture 2012, and hopes to return in 2013 with a nonflying prototype, followed by a visit with an airworthy prototype in 2014. He said the new technology for making parts may help make aircraft builds more feasible, and reduce a high rate of unfinished efforts—as many as three of every four kits started may never be finished. Repetitive tasks, such as making wing ribs, could move significantly faster—a full set made in hours instead of days, months, or years using CNC machines and digital plans. Nicol said a builder would retain control over the manufacturing process, while streamlining the time-consuming task of making individual ribs by hand.

“While we may not necessarily save cost, we’re going to save time,” Nicol said, noting parts are being designed for the LSA kit that will be easy to assemble, thanks to a slot-in-tab architecture similar to that used by Ikea for furniture: the pieces will only fit together one way, the correct way.

The new methods also lend themselves to an educational environment, Nicol said, expressing plans to seek partnerships with schools hoping to enhance their science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) programs.