Buying piston aircraft by the slice remains a boutique option available in a limited number of locations, although that may change with new players jumping into the market. Some are downright evangelical about leveraging the buying power of many pilots to refresh an aging general aviation fleet with brand-new aircraft, or expanding—dramatically—access to aircraft at the lowest possible cost.

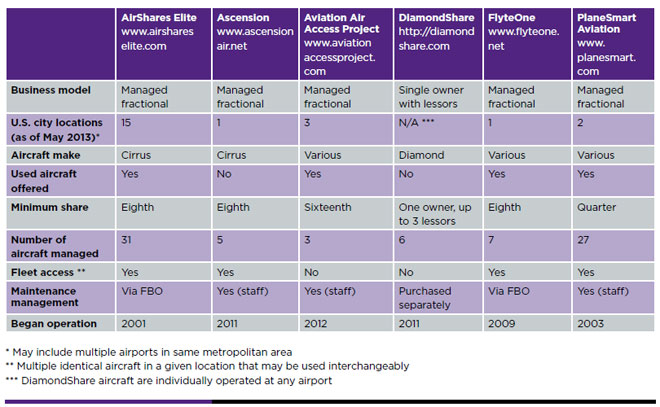

So far, however, it has been tough sledding. Managed ownership of piston aircraft—partnership with a (paid) middleman—dates back a little more than a decade. Although these middlemen report growth—and renewed consumer interest as the economy recovers—the numbers remain small: fewer than 80 piston aircraft in the country are managed by half a dozen companies established so far to manage, to varying degrees, piston aircraft with multiple owners. To some, successful development and expansion of the model is the only way GA can be saved; others focus on serving only the largest markets in the country, catering to customers who value hassle-free flying in state-of-the-art aircraft—and are willing and able to pay for it.

“Fractional” can mean different things, although in most cases it is distinguished from a traditional partnership primarily by the presence of a middleman who provides matchmaking and flight department services for a fee. Unlike the larger market of fractional turbine aircraft (think NetJets, among others), fractional piston owners typically fly what they buy, although some customers may hire a pilot occasionally, or exclusively. There are five companies managing fractionally owned piston fleets ranging from three to 31 aircraft. A recently launched consortium of Diamond Aircraft dealers, dubbed DiamondShare, offers an alternative model mixing sole owners and “members” who lease access to the aircraft, with more limited operational management.

The short history of managed piston ownership includes one disaster: OurPlane, which managed a fleet of more than two dozen aircraft, and declared Chapter 7 bankruptcy in 2010. Its bankruptcy petition lists 48 aircraft-share partial owners owed $10,000 to $32,000 among the longer list of unsecured creditors, with unsecured debt totaling $2.5 million.

“What happened in that situation was potentially devastating to any future [fractional ownership operators],” said Mike Brosler, president and CEO of PlaneSmart Aviation, which operates 27 aircraft, 20 of them Cirrus models, all based in Texas.

Another early player, iFly, was bought in 2008 by AirShares Elite.

The industry learned a lesson from OurPlane’s demise: anyone who buys an equity share in an aircraft being managed in this way is named on the title, and stands to collect proceeds when the aircraft is sold (typically on a four-year cycle) based on the size of the share. Each company provides a degree of scheduling support, either an online system or a staff, and each offers access to group insurance. Beyond that, the details and costs vary considerably.

Lee Sewell, an Atlanta pilot and current owner of a share in a Cirrus SR22 managed by Ascension Air, said she nearly bought into a traditional partnership but missed her chance by minutes. She and her husband, not a pilot but a skilled passenger who can help out with various in-flight tasks, have purchased fractions from both AirShares Elite, the most established company in the managed piston ownership market, and now Ascension Air, which launched in 2012 offering brand-new Cirrus SR22Ts. She reported a positive experience with both companies, although Ascension goes a bit further with its customer service—the concierge staff will even sump tanks as the pilot looks on.

Sewell said both purchase decisions were informed by careful research, including consultation with tax advisors. She concluded that for a pilot planning to fly 100 to 150 hours a year, a fraction makes more sense than a whole airplane; at 175 hours a year or more, sole ownership begins to make more sense, she concluded. Neither of the companies she has available to her has a clear-cut advantage.

Both companies offered excellent availability, Sewell said, with unfulfilled scheduling requests almost unheard of. Other owners of aircraft shares managed by various companies (whose contact information was provided by the respective companies) report much the same: there is almost always an airplane when needed. AirShares, Ascension, and PlaneSmart manage to deliver this kind of availability by assembling fleets of identical (or nearly identical) aircraft in one metropolitan area, sometimes at the same airport.

This variation on the business model offers convenience, but also a limitation: it requires a large population with enough pilots (or potential pilots) able to afford a first-year outlay that can approach or exceed six figures for a share in a Cirrus. (Out-of-pocket expenses can be reduced by leasing, financing, and tax strategies; leasing can bring first-year fixed expenses for the smallest share below $30,000.) It is unlikely that any of these companies will be tempted to set up shop in a city or small town that is unable to sustain more than one or two aircraft.

“You have to be hub-centric,” said Ascension President and CEO Jamail Larkins, who has sold five aircraft in little more than a year, and plans to expand beyond the Atlanta operation to another major market soon. He expects the company will eventually grow into 20 cities, two dozen at most.

Will Stroud, a Dallas pilot and PlaneSmart customer, said the value of fleet access was particularly evident when the aircraft he co-owned was damaged by another pilot in a fuel starvation accident.

“We were still able to fly the other airplanes in the fleet,” while PlaneSmart handled the details of insurance claim and repairs, Stroud said. Like Sewell, he had researched extensively, studying the range of ownership options. There is a price to be paid (fixed management fees for a Cirrus can top $2,000 per month, depending on aircraft, share size, and location), but owners who want the ultimate in hassle-free aviation say it is worth the money.

“It’s certainly not the least expensive way to own an airplane,” said Stroud, who owns a real estate company and is looking to upgrade to a turboprop or light jet. “It’s definitely the gourmet way to fly.”

Rick Matthews was with AirShares Elite, but recently he assembled a new team and created a company that aims to make aircraft available to all. Aviation Access Project, based in Gallatin, Tennessee, has only just begun to realize a vision of operating low-cost aircraft, including Light Sport and used models, at small airports across the country. Each flight center would combine training, aircraft management, and opportunities for pilots to socialize—a key ingredient in Matthews’ formula that is absent from many other managed fractional programs.

“We are redefining the industry,” Matthews said. “What has been happening has been failing us.” He said the effort was inspired in large part by AOPA research on flight training that found between 70 and 80 percent of student pilots never earn a certificate. Matthews turned his attention to making airplane access as affordable as possible, and scoffs at an analysis that precludes all but the most populated areas as fertile ground for fractions.

“We don’t just want to make money in this,” Matthews said. He envisions 1,000 flight centers spread across the country, offering equity buy-in options of $10,000 or less, and monthly management fees starting around $100 per shareholder. “We’re in this to literally transform the industry.”

John Armstrong founded Diamond-Share with fellow Diamond dealers—and a different business model that blends ownership and leasing: each brand-new Diamond is sold to a single owner, and Armstrong will recruit up to three additional “members” willing to make one-year commitments to pay $999 per month for 8.3 hours of monthly DA40 use, excluding fuel. Those payments defray the owner’s cost, which may be reduced further by tax deductions and depreciation. (The same is often true in other shared ownership programs.) Armstrong said the idea is to put a brand-new $420,000 aircraft within reach of pilots who otherwise would never dream of it.

Most pilots can’t justify the expense of a state-of-the-art aircraft, Armstrong said, relegating them to decades-old airplanes and technology. In turn, dealers have a hard time selling new aircraft, and the GA fleet continues to age. Owners of 30-year-old (or older) aircraft are being driven out of aviation by the ever-rising cost of maintaining an aircraft priced within their means.

“They get beat up by the shops and they just leave,” Armstrong said. “They quit flying. That’s the worst thing that can happen. We have to find ways to get modern airplanes out there in larger numbers, or this industry is going to slowly just die.”

Armstrong and his fellow dealers have sold six DA40 aircraft divvied up in this way, and plan to adapt their model for the DA42 twin in the near future.

In st. petersburg, Florida, FlyteOne President Alex Atteberry offers yet another take on managed fractional ownership, not tied to any particular make or model. He began working on his own plan in 2008, and offers management services for a broad range of aircraft: turboprops and jets at one end, and eventually offering Light Sport shares at the other. In between, the company manages single-engine certificated pistons like the Piper Cherokee Six for a total fee of $20,000 per year, divided by however many owners buy a share.

Atteberry said the program—which advertises buy-in costs as low as $10,000—is just being launched, and a half-dozen locations across the country are being explored as potential bases. He sees potential for many more than the six aircraft currently under management, as customers who once might have opted to buy alone are now willing to join forces for lower costs.

“I think a lot of it has to do with a big paradigm shift, from I have to own it,” Atteberry said, “to, I own it, I’m in control, but I don’t have the headaches.” He expects the managed ownership model to gain traction as owners realize that comparable utility can be had for a fraction of the price, even when paying for maintenance, storage, insurance, and other details.

“What I look at with what we’re trying to deliver—you may be flying alone, but you’re not alone,” Atteberry said.

Email [email protected]