Illustration by Alex Williamson

In 1969, there was a humorous short cartoon—very short—titled “Bambi Meets Godzilla.” In it, a tiny Bambi is mashed flat under Godzilla’s huge reptilian foot. This more or less represents the essence of the relationship between general aviation and governments—as well as their regulatory bodies. Over the 75 years since AOPA’s founding, its principal goal has been to prevent GA from suffering a fate analogous to Bambi’s. Yes, AOPA’s charter gives the association three main goals: to make flying easier, safer, and more fun. But without effective advocacy in the federal, state, local, and regulatory arenas, none of that could ever happen.

AOPA was fortunate to have been founded by a group of Philadelphia lawyers and industrialists who were as committed to flying as they were to defending GA interests. By early 1939, it was clear that airline and military aviation lobbyists were winning out over private-airplane interests. AOPA’s six founders knew that general aviation needed a single, strong voice to ensure its future. Consequently, AOPA put a high priority on political work from day one. In this it was alone among other organizations purporting to represent general aviation interests.

So what would general aviation be like without AOPA’s influence?

Until AOPA initiated information-sharing meetings with President John F. Kennedy’s newly appointed FAA administrator, Najeeb Halaby, there was no way for pilots to appeal charges of violating the federal aviation regulations. The administrator acted as judge and jury, with no questions asked. It was AOPA, drawing on support cultivated from sympathetic senators and representatives in the late 1950s, which was instrumental in ensuring a pilot’s right to question his questioners.

When Terminal Control Areas (TCAs, now known as Class B airspace) went into effect in late 1969, it was the culmination of more than 10 years of governmental efforts aimed at keeping general aviation aircraft flying under visual flight rules (VFR) away from high-density traffic. But AOPA succeeded in establishing VFR transition, climb, and descent corridors at some locations.

Confusion surrounding the nature and terminology used in an approach clearance became an issue after the 1974 crash of a TWA airliner flying into the Washington-Dulles International Airport. AOPA asked for a pilot/controller glossary so that future misunderstandings could be avoided. The request was granted.

Other initiatives were equally successful, thanks to AOPA. Fees for pilot examinations and certificates were dropped from consideration. National Ocean Survey approach chart binders were scrapped in favor of disposable, bound volumes. Flight Watch services were brought to the eastern United States. Money in the Airport and Airways Trust Fund was spent on developing America’s aviation infrastructure, and not on the FAA’s day-to-day expenses.

A plan to expand the number of TCAs to 65 was rejected after a midair collision between an airliner and a Cessna 172 (the airliner was at fault, and both airplanes were within a TCA) near San Diego caused near hysteria about small airplanes flying in busy airspace. The epithet “If you ride a bicycle, don’t drive on the beltway” increasingly summed up public attitudes toward general aviation. A bill supported by one congressman even proposed shooting down general aviation airplanes entering the United States from the Bahamas, on the pretext that they might be importing illegal drugs. AOPA was instrumental in nixing it.

Citing high product liability insurance premiums, general aviation manufacturing took a nosedive in the 1980s. AOPA and its industry allies pushed through reforms that in 1994 set a statute of limitations on product liability lawsuits. The production lines went back into action.

The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, renewed AOPA’s role as pilot educator. In the months after the attacks, the organization worked hard to provide accurate, timely information on temporary flight restrictions (TFRs), intercept procedures, and notams affecting national security. In many cases, the information was presented more coherently than that issued by the FAA. Today, TFR information is emailed to members in the surrounding area as they are posted.

Efforts to reverse the decline in the pilot population have been another AOPA hallmark. Numerous programs designed to boost pilot-training activity, draw younger pilots into the fold—and prevent current pilots from dropping out—have been launched. AOPA has also backed the Light Sport aircraft industry’s efforts in appealing to new pilots, and retaining the existing pilot base through simpler designs. Another, recent effort is AOPA’s argument to allow more pilots to use driver’s licenses in place of medical certificates, in essence self-certifying themselves in much the same way that glider and balloon pilots always have.

AOPA also has been successful in repeatedly blunting the federal government’s ongoing initiatives to impose user fees. Preserving the existing funding mechanism—aviation fuel taxes—is the most efficient and fairest way to move forward.

All of the above are just a few of the ways that AOPA has made a difference over the years. So where would we be if AOPA hadn’t emerged on the scene in 1939?

There would be fewer pilots than there already are; restricted—or no—access to Class B airspace; more Class B airspace; no unified, powerful influence in Congress or before the FAA, various levels of government, and other regulatory bodies; no unicoms; no ASI educational programs and courses; no ability to appeal FAA enforcement actions; no legal plans tailored for pilots; no medical staff providing expert advice to pilots; an already-diminished general aviation industry diminished even further by lawsuits; no unified international representation; fees for airman certificates and medical exams; and user fees for filing flight plans, using navaids, landings, and who knows what else. Oh, and for that matter, no AOPA Pilot, ePilot, or AOPA Live This Week.

Over the years there have been those inclined to disparage AOPA, for whatever reason. But critics should bear in mind that when it comes to advocacy for general aviation pilots and their interests, AOPA is, bar none, the most effective force. Who else has a full-time staff of 200? Who else has the membership numbers and lobbying savvy to effect change in our favor? Where else can you go for expert advice, just by picking up the phone or emailing? It takes more than a website or raw opinion to get things done in the venues that matter. AOPA knew this from day one, and we’ve all benefitted—even those who aren’t members.

Email [email protected]

AOPA’s first success came with the passage of the Civilian Pilot Training Program (CPTP)—a federal program that let thousands of new pilots earn their wings with help of a subsidy. These pilots would later serve in World War II, and continue flying—in general aviation airplanes—long after the war. AOPA secured passage of the Senate bill clinching the CPTP by the painstaking art of Congressional persuasion and consensus-building. It’s work that takes time, patience, and tactful behind-the-scenes arm-bending. And it continues to this day. Without the CPTP effort,

general aviation wouldn’t have registered on the federal government’s radar. And a

generation’s worth of pilots never would have begun.

In the prewar days other initiatives broke new ground. AOPA began to exert pressure on manufacturers and the National Advisory Council for Aeronautics (NASA’s predecessor) to standardize instrument panel design, and build aircraft with safety in mind. Without this initiative, it’s doubtful that stall-resistant designs like the Ercoupe would have come about.

After World War II broke out, the federal government sought to ban all general aviation flying, everywhere in the United States. AOPA responded by using its newly founded Air Guard units to register GA pilots and issue them identification papers. Once registered, pilots could fly everywhere but the coastal air defense areas. Thus began a tradition of AOPA cooperating with national security guidelines without sacrificing general aviation’s right to fly.

After the war, an avionics revolution began with introduction of VOR and ILS navigation equipment and procedures. Without AOPA’s educational mailings to members, it’s doubtful that the switch to this then-radical form of navigation would have been as smooth. At the same time, AOPA argued that the old low-frequency radio range navigation stations be phased out gradually so that pilots could become more accustomed to the new VHF-based technology. The government wanted to ditch the radio ranges abruptly. Sound like today’s switch from VOR/ILS navigation to a system based on GPS alone?

By the way, in 1955 the government proposed ditching VORs and ILSs in favor of a UHF-based system of TACANs (tactical air navigation systems) pushed by the military. If it got its way, VORs would have been decommissioned by 1965. But AOPA championed a winning alternative: collocating certain existing VORs with TACAN in a network of VORTACs.

With the debut of the Air Safety Foundation (known today as the Air Safety Institute) in 1950, training programs escalated. The “180-degree” and “360-degree” courses, designed to help noninstrument-rated pilots safely exit clouds, became popular—and saved lives. ASI continues this work today, with its many online courses and videos. The ASI also began its popular Flight Instructor Refresher Courses (FIRCs), which empowered the organization to recertify flight instructors by taking a three-day course; later, the course was shortened to two days.

In 1952, AOPA came up with the idea for a common radio frequency pilots could use to share airport and weather information. No such capability had existed, but government and industry agreed it was a good idea, so AOPA’s “universal communications” frequency (quickly dubbed “unicom”) came alive. Where would we be today if nontowered airports didn’t have unicoms on which to announce our positions and intentions?

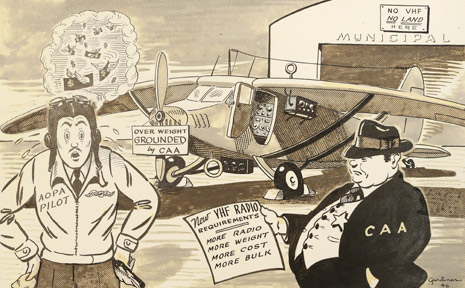

Back in the late 1940s, radio communications were not nearly as mandatory as they are in today’s complicated airspace. When the government tried to force general aviation pilots into purchasing the heavy, tube-laden radios of the day, AOPA attempted to impart some common sense into the debate. The cartoon makes the point—although today it seems ultra-reactionary in view of more modern communications requirements.

In this 1947 cartoon that appeared in an “AOPA Pilot” insert in Flying magazine, AOPA is shown warning of a wave of new rules from the then-new Provisional International Civil Aviation Organization. Meanwhile, the Civil Aeronautics Authority (CAA, the FAA’s forerunner) is lying down on the job, even though one of its ostensible goals is to promote aviation.