Illustration: James Carey

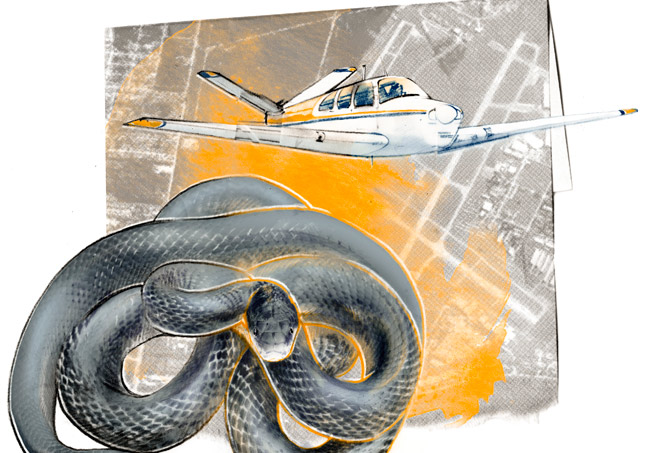

Once upon a time, two men were flying in a Bonanza across Florida, from St. Petersburg to Vero Beach. It was a warm day, VFR weather, but with occasional isolated showers that are typical of that part of the country.

The two men were J.B. “Doc” Hartranft Jr., AOPA president, and myself. The airplane was mine, N13K. The date was October 17, 1958. It was the third day of the five-day Plantation Party flight for AOPA members at St. Petersburg. Most of the customary crises that crop up during the first day of such a complex affair had been solved, so Doc and I decided to stop by Cypress Gardens, where part of the AOPA group was spending the day, then go on to Vero Beach, where we planned to have lunch with Fred Weick (AOPA 009893), director of Piper’s research and development center there. This all seems innocent enough, and routine. But I should have known my luck doesn’t lean toward simple routine.

We stopped at Tampa for a brief discussion of weather-briefing plans with the head of the Weather Bureau facility there. Then we hopped the few miles over to Cypress Gardens. At that small airport we found that it would be too complicated and difficult to get ground transportation to come to the airport for us, take us to the AOPA gang, then bring us back in time to catch up with Weick. So we decided to fly on to Vero Beach.

It’s 83 miles direct from Cypress Gardens to Vero Beach, so I stayed at 2,500 feet. As we headed across Lake Kissimmee, I pondered what looked like a fairly heavy rainshower across our course up ahead. Doc was studying the map and trying to identify some of the few identifiable landmarks out there over the swamps. The rainshower turned out to be heavy smoke from a burning swamp area. I could see through it, so I didn’t alter course. I was tuned to the Vero Beach omni, and was just flying the centered needle inbound.

As we passed through the smoke cloud, I scanned the area around the airplane, then glanced back out the rear window over my right shoulder. I was already turning my head back to the front when I sensed, more than saw, something among the charts and Jeppesen flight case on the backseat. I did a quick double-take and found myself staring straight into the beady eyes of a snake that looked like he was at least three feet in diameter, a mile long, and breathing fire and smoke through foot-long teeth.

I can only paraphrase (loosely) my first words to Doc:

“Heavens to Betsy, Doc, there’s a Heavens to Betsy snake in the backseat!”

I think he thought I was kidding, until he turned and looked.

Maybe my reaction would have been a bit different if the darned thing (another loose paraphrase) had just lain there quietly on the backseat. But not Montmorency; he was all over the place. Up over the flight bag and onto the shelf behind the backseat, down onto the floor, back up toward the rear sun visors, down along the right-hand cabin wall toward Doc’s seat. A couple of times he stuck his nose up between Doc’s seat back and the wall, apparently looking for a way to get forward into the front seat. I could see this from the left-hand seat, but Doc couldn’t, so I kept him posted.

All I could think of was that this was Florida; Florida’s crawling with deadly poisonous snakes; and that we’re stuck in midair over one of the swampiest parts of the damned state. Then I began looking for someplace to land—quick. There was one little two-lane road to the left, with a truck throwing up dust along it. I pointed it out to Doc and suggested we’d better get down on it while the getting’s good.

Doc once was bitten by a rattlesnake (I found out later) when he was a boy. From the way he acted, he was assuming that this one also was deadly poisonous—an assumption with which I concurred exactly 164 percent. Doc knew that the most important thing we should do is to move slowly, deliberately, and do nothing to startle Montmorency because, as Snakeologist Hartranft pointed out, snakes just naturally take a poke at anything that makes a sudden movement. So I settled down to trying to be panic-stricken slowly and deliberately.

When I suggested we get the hell down on the dirt road, Doc apparently assumed I was about to go beserk—an assumption for which I don’t particularly blame him. He immediately devoted his life’s work to speaking soothingly and comfortingly to me. Looking back on it, I think he was trying to soothe two savage breasts with one whisper, because he looked a little gray around the chops too (he says it was reflection of the overcast sky I saw).

By this time I’d had plenty of time for about 75 terrified looks at Montmorency. He was still touring the inside of that airplane at a great clip. The only thing that kept me from touring right with him was the seatbelt—and our program of slow and deliberate movement.

In a while I almost began to get used to our passenger, probably because I was still alive, and he hadn’t attacked either Doc or me.

Although the skin on the back of my neck was still operating like an accordion playing Twelfth Street Rag, I began to think ahead. Near as I can figure, when I collected my senses enough to go back to the business of flying the airplane, we were still about 40 miles out of Vero Beach.

Then something prompted me to pick up the mic—slowly and deliberately, of course—and call the CAA station at Vero Beach:

“Vero Beach Radio, Bonanza One Three King.”

“Vero Beach Radio, go ahead One Three King.”

“Anybody down there know anything about snakes?”

A startled silence for a moment, then:

“Why? What’s the trouble?”

“I’ve got a big black one staring me in the eye.”

There was another rattling of the mic in the station, then another voice:

“What’s it look like?”

“It’s long, it’s black, and it’s moving around the back of the cabin at a great rate.”

He thought for a moment, then:

“Is it a dull black or a shiny black?”

This required another quick study of Montmorency.

“Shiny.”

“Hmmm. Sounds to me like it’s a black snake. Black snakes are shiny. Gopher snakes are dull. Neither one is poisonous. But I wouldn’t recommend you fool with him if he’s a gopher snake, because although they’re not poisonous—gopher snakes kill rattlesnakes.”

Me fool with him? Silly boy. I cringe at touching an angleworm.

By now we were crossing something called Blue Cypress Lake, about 22 miles from the Vero Beach airport. Doc was still soothing me. He suggested I pull my socks up over my pant legs “just in case.”

All the time I kept remembering the many Zoo Parade TV programs I enjoyed so much, with Marlin Perkins very expertly juggling all kinds of snakes, virtually all deadly poisonous. I remembered that he used a special “snake stick,” which looked like a golf club with a flat right-angle piece of metal at the bottom. He’d just put that piece of metal gently behind the snake’s head, pin the head firmly to the ground, then reach down and pick him up at the spot where the snake stick was holding him. After a couple of furtive glances around the cabin I confirmed my suspicion: I’d neglected to bring a snake stick.

Now we could see the airport ahead. I reached for the mic, half expecting the black coiled cord to suddenly turn into Montmorency.

“Vero Beach Radio, Bonanza One Three King about 10 west.”

“Roger, One Three King. The winds are favoring Runway Three Left.”

“Any other traffic around?”

“No local traffic, but an Eastern flight’s due here in about four minutes.”

“Well, I’m taking Runway Three Left. I’m going to use it indefinitely if I have to, so you’d better tell Eastern to use another runway.”

“Roger, One Three King.”

Then Doc and I furtively glanced back to see where Montmorency was. No snake! We scanned the whole rear of the cabin, but no snake. I began to cringe again, suspecting that the little dear had finally made his way into the front, and was even now toying with my toes.

But no snake was in front, either. By this time I was on a long base for Three Left, so I gingerly pushed the gear-down switch. Still no snake to be seen. I lined up on final, then put down the flaps. Doc and I were still alone.

I landed like I was balancing a hydrogen bomb on the tip of my trembling finger. Slowly, we rolled to a stop. We carefully unhooked our belts and took a thorough look around. Our buddy was gone. Maybe he’d crawled down into the structure somewhere, then fell out when the gear was lowered.

I taxied slowly to the ramp, and pulled up the flaps. After cutting the engine and turning off all the switches, I reached for the door handle—slowly and deliberately, remember. Doc began to laugh, held his hands up in front of his face like he was playing a flute, and began whining that snake-charmer music through his nose.

But I wasn’t having any. I wanted out, and out we went. We stood on the wing, looking all over the cabin. No dice. Then I figured Montmorency might be back in the baggage compartment. So I gingerly unlocked the door. No snake. Doc got the nosewheel towbar and began poking around among the charts and miscellaneous papers in the backseat and on the shelf. No snake.

We had us a small crowd by this time, including the CAA boy who had given me the facts on snake life. But I noticed they stayed at a distance, snickering at Doc and me with our socks over our pants.

By this time I had started to unhook the seat cushions, because we were either going to find that snake or I wasn’t going to fly my airplane back to St. Pete; to Washington, D.C., or anywhere else. Suddenly, one of Eastern’s baggage handlers let out a yell: “There he is!” He was pointing to the left wing tip.

We all ran around the ship and there was Montmorency, hanging half out of an aileron hinge hole, trying to figure out how to escape from this noisy monster. The first thing I could think of was to grab my camera.

After I shot the picture, the CAA fellow went over, jerked Montmorency briskly by the fuselage a couple of times, and pulled him all the way out and put him on the ground. That’s when I took a second picture.

Monty was a black snake, all right, and the CAA man picked him up by the tail and carried him off to the tall grass. No, you should never kill black snakes, he said; they’re very beneficial, et cetera, et cetera. I was a bit skeptical.

Near as I can figure it, Monty could have joined our party at Cypress Gardens, or at St. Pete, where the airplane had been tied down in the grass for several days. Or at Guntersville, Alabama, where we had stopped overnight on a small strip (with deep grass) on the way south. He probably crawled up a wheel and landing gear strut, into the wing structure, then around through the many lightening holes, through a control opening, into the cabin. Priority No. 1 has been to get those holes around the landing gear and wheel wells plugged up.

So as far as I’m concerned, you’re welcome to all the snakes in the world.

That goes for Marlin Perkins’ snake stick, too.

Max Karant served as editor of AOPA Pilot from 1958 through 1976.

It was 1959

It was 1959

Max Karant was the founder and first editor of AOPA Pilot magazine, a position he held for 18 years. In addition to being AOPA member number 18, he was the association’s second full-time employee. He wrote this “Never Again” tale for the January 1959 issue of the magazine.

“Never Again” continues to be one of the most popular departments in the magazine, and many members say it’s the first page they turn to when their issue arrives. Members can listen to “Never Again” via podcast from AOPA Online or Apple’s iTunes. The Best of ‘Never Again’ Volumes 1 and 2 can be purchased in eBook format on AOPA Online.