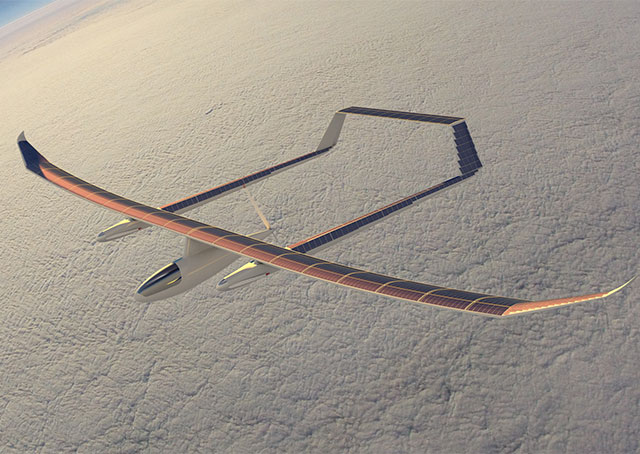

Three electric motors will drive Sunstar, one of them turning a huge centerline-mounted propeller that must be feathered for takeoff and landing or it would strike the ground. Solar Flight President Eric Raymond hopes the prototype will fly in two years, with a pilot working the controls—if only for testing.

Raymond, who has been designing and building solar-powered aircraft for nearly three decades, said Sunstar is designed with autonomy in mind because it has turned out that solar power is marketable only for specialized missions: Sunstar will be offered primarily as an “atmospheric satellite,” functioning as a communications relay station, for example, or handling other missions currently performed by satellites in space, at a fraction of the cost of those satellites.

Raymond said that was not the plan starting out, but the market has spoken.

“I don’t seem to be in the manned aircraft business,” Raymond said in a telephone interview. “We haven’t sold anything in 28 years … maybe the first 30 years are the hardest.”

Sunstar is the fourth solar-powered aircraft designed by Raymond and his team of visionaries, and Solar Flight, based near San Diego, promises it will be well-suited for the real world, more tolerant of turbulence than similar systems, and capable of holding station at high altitude for months on end. Many of the systems and components will be adapted from Sunseeker Duo, the two-seat solar aircraft Raymond had once hoped would catch on. Raymond said he still sees a limited market for electric aircraft, noting that Pipistrel recently announced its own take on the two-seat electric trainer. But electric trainers have their limits—pilots trained on electric powerplants will have to adapt to and learn the ways of combustion engines, eventually—and Raymond said the broader light aircraft market has been pretty clear about what it wants.

“Everybody wants a four-seat airplane that fits in a two-car garage,” Raymond said.

By staying in the atmosphere, Sunstar can achieve faster communication speeds than a satellite because of the shorter distances involved. Raymond plans to make it a manned vehicle for testing to avoid the restrictions imposed on unmanned vehicles. The central pod can be fitted with a cockpit, as well as batteries and electronics. Eventually, the pilot can be replaced with payload—including more batteries, the technology of which has progressed more slowly than Raymond once hoped. They still weigh a lot for the amount of energy they can store, while solar cells have advanced swiftly in recent years. Solar Flight has developed a proprietary lamination method that will give Sunstar a smooth skin, contributing to the efficiency required to maintain a high-altitude station for extended periods. The central motor driving that oversized propeller is designed for high-efficiency operation at altitude; the other two motors will be shut off once Sunstar reaches altitude, and their propellers stowed inside the airframe until needed again.

Raymond said there is plenty of interest in unmanned aircraft able to remain on station for extended periods of time, fueled by the sun. Sunstar is a modular design, which can be fitted with a variety of equipment, and even have its wingspan adjusted by adding or removing sections, the way one might expand a dining room table for the holidays and then shrink it for daily use.

“A lot of the customers I talk to have different payload requirements,” Raymond said. “I am hoping to produce several sizes.”