A life in general aviation

South Carolina aviators honor J. Reid Garrison

The next time a line attendant marshals you to parking at an unfamiliar airport after your long day’s flying, and reappears the next morning to fuel the aircraft for your predawn departure, be sure to show appreciation. You may be in the presence of the FBO’s next owner, or even a future aviation hall-of-famer.

That was how a piloting life began for AOPA member Jesse Reid Garrison. In the 1950s, line work at his local South Carolina airport paid $1 an hour. Or you could barter your labor for flight lessons. Garrison, in one of aviation’s rich traditions, availed himself of both methods to launch an aviation career that was honored on Feb. 12 when he became an inductee into the South Carolina Aviation Hall of Fame.

“I always dreamed about it, but I didn’t think it would ever get here,” said Garrison, 79, in an interview in which he discussed a career that has touched almost every aspect of general aviation, and allowed him to fly an astounding assortment of aircraft.

“When you get older you forget how many miles you traveled,” he said.

If his name sounds familiar, you may know J. Reid Garrison as an airshow performer and formation pilot who has been part of the story line at the major aviation events, including Sun ’n Fun in Lakeland, Florida, and EAA AirVenture, in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, across the years. He also is a member of EAA’s Warbirds of America group.

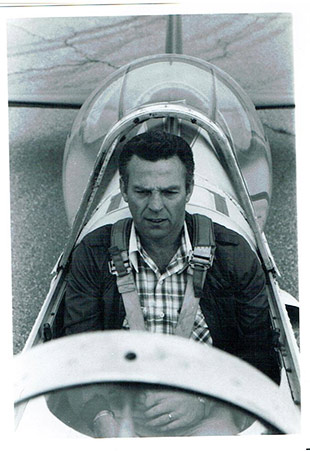

You may have seen Garrison—nicknamed “Speedy” on the circuit—performing aerobatics in a de Havilland DHC-1 Chipmunk such as the one he acquired in 1972 from airshow performer and stunt pilot Art Scholl.

Garrison also may be familiar to you as the winner of aviation-event judges’ appreciation awards and outstanding aircraft honors for his warbird restorations that include two proudly revitalized Beechcraft T-34 Mentors, a North American T-28, two North American T-6Gs, and 12 Chipmunks.

Hangar flying by phone, Garrison makes a pilot long for a stick and throttle as he relates the joys of maneuvering the agile Chipmunk, or as he narrates the nuances of making an inverted pass in the 8,500-pound T-28.

“You’ve got to manage your mass, as Bob Hoover used to say,” Garrison explains.

What’s a path to induction into an aviation hall of fame? Accomplish what’s noted above for starters. Fly with the Blue Angels; operate two full-service, family-run fixed-base operations; work as a charter pilot for your alma mater—Clemson University, in Garrison’s case—and transport its presidents and coaches. Establish and serve as director of operations (as he did until 2011) of the first helicopter medevac operation to be certificated by the FAA’s South Carolina Flight Standards District Office.

What’s a path to induction into an aviation hall of fame? Accomplish what’s noted above for starters. Fly with the Blue Angels; operate two full-service, family-run fixed-base operations; work as a charter pilot for your alma mater—Clemson University, in Garrison’s case—and transport its presidents and coaches. Establish and serve as director of operations (as he did until 2011) of the first helicopter medevac operation to be certificated by the FAA’s South Carolina Flight Standards District Office.

Flight instructing has been a traditional launching pad and mainstay for many pilots’ careers in general aviation, and that was the case for Garrison, who still teaches flying. (When pondering his career path, flight instructing won out over teaching engineering and math, which he also was certified to do.)

Learning to fly in a Luscombe, Garrison earned his private pilot certificate in 1959. Graduating from Clemson in 1960, he entered the army as a second lieutenant, took helicopter training, and served as a helicopter pilot and instructor, until returning to civilian life in 1963. Then he became a flight instructor and mechanic at South Carolina’s Anderson County Airport.

A contract to develop an FBO at the Clemson-Oconee County Airport followed in 1965. There, Garrison trained army and Air Force cadets from Reserve Officer Training Corps programs.

In 1975, he became the owner of Anderson Aviation, Inc., and operated both airports’ FBOs as full-service businesses, offering flight training, charter and helicopter service, maintenance, and an avionics shop.

In 1979 he sold the Clemson-Oconee operation to Oconee County, continuing to operate the Anderson County Airport’s FBO until 1999. Both his sons, Jeff and Brett, are pilots, and his wife and daughter have worked in the family aviation businesses.

‘That saved my life’

Garrison’s stories of a life in aviation are rich with chapters on flying King Air turboprops, fast Aerostars, freight dogs, and sleek singles, but his talk turns to the Piper J-3 Cub when discussing how a student pilot ought to undertake primary flight instruction. If there’s no Cub available, make sure to learn in something that will teach you how to use the rudder pedals to maintain directional control. No taildragger available? Just make the right choice between whatever makes and models of tricycle-gear aircraft are available. (That is, pick the one that makes you use your feet.)

Garrison always loved to “go fast.” So it was only the timely clicking-closed of an automobile seatbelt in 1959—a habit acquired from driving race cars at a time when seatbelt use in autos was uncommon—that prevented Garrison’s aviation career from ending almost before it had begun. A car crash severely injured him and disfigured his nose, requiring three subsequent surgeries. He’s sure the seatbelt spared him a crueler fate.

“Every day I think about that,” he said. “That saved my life.”

With the settlement proceeds, he bought a Cessna 140.

The South Carolina Aviation Hall of Fame was established in 1991 to honor “pioneers and leaders in the aviation industry who have made significant contributions to the development, advancement or promotion of aviation and have close ties to the State of South Carolina.” Inductees may be chosen for “a single gallant event” or for “achievement over time.” Either way, Garrison should be in most comfortable company with his honored peers.