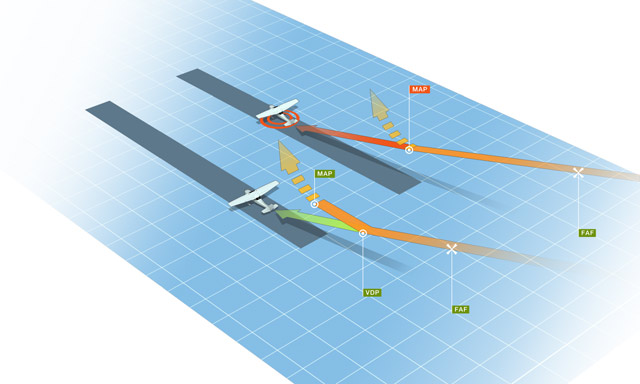

With a published visual descent point (VDP), the pilot approaching the left runway has enough time and distance to land in the touchdown zone. Some nonprecision approaches have their missed approach points (MAPs) right over the runway threshold (right runway). This leaves you too high for a normal descent, so pilots can be tempted into diving for the runway, and landing long.

The approaches voted most likely to be unstable

In the past two installments of “On Instruments,” I discussed the ILS approach—one of the most accurate methods of providing guidance to a runway when ceilings and/or visibilities are below visual meteorological standards. This time, let’s talk about nonprecision approaches: those without glideslope or other vertical guidance. These procedures—whether they’re VOR, RNAV (GPS), LDA, SDF, or NDB approaches—carry extra risks and require higher levels of skill and judgment. Not just because the lateral guidance may be different and much less precise than an ILS, but because you must manage your own descents from the final approach fix (FAF) to the missed approach point (MAP)—and beyond.

While WAAS-enabled LPV (localizer performance with vertical guidance) and LNAV/VNAV (lateral navigation/vertical navigation) GPS approaches do provide glideslope-like information, these still are considered nonprecision approaches—even though minimums can be as low as 200 to 250 feet agl in the case of LPV approaches. In this article I’ll concentrate on traditional nonprecision approaches—those having no vertical guidance.

The minimums for these sorts of approaches generally run around 500 feet agl, with one statute mile visibility. The strategy most often taught is to descend promptly to the minimum descent altitude (MDA), immediately after passing the FAF inbound.

This way, you maximize your chances of getting beneath any clouds and improve your chances of seeing the runway, runway complex, or runway environment. That’s all very nice, but remember that you’re very busy on the final approach course (FAC). You’ll be watching your elapsed time to get from FAF to MAP, for one. Unless you have a DME- or GPS-defined MAP, that’s the only way to know when you’ve reached the MAP.

But more important, there’s the visibility to consider. That minimum one-mile visibility is everything. Let’s say the visibility is one mile, for example, and you spot the runway. You’re still at your 500-foot MDA, and must now rapidly lose that 500 feet if you’re to arrive at the touchdown zone in style. The urge to complete the approach is compelling, so the temptation is to take aim for the runway, picking up airspeed in the process. So begins the setup for a runway overshoot. This “dive-for-it-splat” incident or accident has happened to many pilots.

Approaches with visual descent points (VDPs, marked by a small “V” on the profile views of a nonprecision approach chart) anticipate this problem. VDPs are good things indeed, because they mark the point where a normal descent angle/rate to the runway can begin. So hooray for them, and seek them out when you do your flight planning. No runway in sight when you arrive at the VDP? Then execute the missed approach. And whatever you do, don’t be tempted into diving for the runway should you catch sight of it while climbing away.

One way to avoid this trap is to create your own VDP, by making the missed approach call before the published MAP. Simply subtract a minute or so from the approach plate’s published FAF-to-MAP time.

Another huge challenge of nonprecision approaches involves circling. Circling approaches provide arrivals to more than one runway. For example, your FAC may align roughly with one runway, but the wind direction is favoring another. With a circling approach, as the name implies, you circle around the airport, at all times keeping the landing runway in sight, and maneuver at the circling MDA until you’re in a position from which a descent to land on the chosen runway can be made at a normal descent rates using normal maneuvers. But there’s nothing “normal” about circling approaches.

Think about it. You spot the runway and must circle within a very tight radius. That radius is based on your airplane’s stall or minimum steady flight speed (or VREF, in the case of turbine airplanes). The airplanes most of us fly are in Category A (stall speed of 91 knots or less), which means a circling radius of a mere 1.3 miles. So there we are, low to the ground, with a minimum of 300 feet of obstacle clearance, banking and slowing for the landing—and looking outside for the point at which we can begin the descent down final.

Throw in nighttime conditions, some distracting lights on the surface, and/or some low-lying clouds, and it’s a recipe for disorientation and vertigo at the least—or a turning stall on instruments at worst.

No wonder so many airlines prohibit circling approaches. That might be a good policy for general aviation pilots, as well.

Email [email protected]

Illustration: Charles Floyd

How’s this for a one- shot procedure?

The approach plate at Sparrevohn, Alaska, includes a note saying, “Successful go-around improbable if initiated past the MAP.”