The manufacturing might of Michigan is back, but it’s not imported from Detroit. It’s made in Menominee.

After years of toiling at the bottom, Enstrom Helicopter is making a comeback, spurred on by some old-fashioned sales work—and, yes, a bit of a bailout.

None of this is evident from the outside. The logo hanging on the front of the building hasn’t been updated in decades. And the lobby, which has, is nondescript. From the wood paneling in the CEO’s office to the cubicle-strewn layout of the technical support group, nothing about Enstrom’s front offices gives the impression of a company on the rise. Travel down a small hallway past ads for old Ford pickup trucks, the stale coffee, and union meeting posters; take the door on your left; and it all changes. The factory is humming.

How it came to be this way is more complicated than some would like to make it. The overly simplistic explanation for the company’s success is the Chinese. The Chongqing Helicopter Investment Co. purchased Enstrom in late December 2012, and despite the xenophobic fears of yet more American jobs moving offshore, the new owners immediately invested big in Menominee. They doubled the size of the factory, and today it rivals anything you’d find in Wichita in terms of technology, quality control, and workmanship. The new ownership also has enabled the introduction of a new model—the TH180 training helicopter—something not seen from Enstrom in decades.

What’s happening on the manufacturing floor today has little to do with China’s hunger for American aerospace companies, and everything to do with the current leadership. Enstrom toiled for nearly a decade to secure foreign military training contracts, the final destination for the majority of this year’s and last year’s machines. From Japan to Peru, Enstrom has found success with its turbine-powered 480B for what it thinks are two primary reasons—a record of safety and a void Bell left when it pulled the Jet Ranger off the market.

Years ago key staff, including current CEO Tracy Biegler, saw that private sales were slumping, and the international military and national defense market was expanding—in part because of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Enstrom staff made the decision to chase those contracts and go for the group sales. “The reason we’re international is that we’ve found a niche market in the training environment,” Biegler said. The result is a 480-percent increase in deliveries over just two years. The five helicopters Enstrom delivered in 2012 were barely enough to keep the doors open and 70 staff members employed; last year’s 29 meant having to more than triple the staff and double the size of the factory.

This somewhat unglamorous story of hard work and quiet dedication defines the company. The website is outdated, the marketing isn’t flashy, and the products remain largely unchanged over the past decade (an exception is the Garmin G1000H in the turbine 480B), but what Enstrom does produce is highly respected, and its customers are loyal.

Enstrom’s lineup has remained stagnant—consistent might be a more generous term—for the past 22 years, when the turbine 480 was introduced. Developed to vie for the Army’s NTH, or Next Training Helicopter, contract, it competes in the same class as Robinson’s R66 (and Bell’s new Jet Ranger when it is certified). Enstrom obviously was unsuccessful in the Army bid, which executives claim was due more to their lack of lobbying ability than a losing design.

There’s probably some truth to that. The helicopter is stable, reliable, and excellent for initial turbine experience. It also has roughly the same interior dimensions as a Mack truck, allowing room for the contract-mandated observer position. Early in the new millennium Enstrom added some badly needed power; upped the gross weight; and certified the B variant, which is still sold today. The G1000H was added last fall, marking probably the biggest certification project out of Menominee in more than 10 years.

Two piston models round out the lineup. The F–28 is now on the F variant, and it remains in many ways the same helicopter that was certified in the 1960s, launching the company. Updates include a more powerful, turbocharged HIO-360 engine that produces 225 horsepower up to 12,000 feet, and a mechanical correlator. Depending on who you ask, the latter is either a nice modern advancement or a threat to a helicopter pilot’s ego. I’ll take progress.

The other piston model is a bit of a curious case. It’s the same aircraft with nothing more than a different fiberglass nose. Called the 280FX or Shark, it’s akin to buying the sport package for a new car that features only a body kit. Developed under F. Lee Bailey’s leadership, the Shark was very popular when it was introduced. Bailey’s instincts said the F–28 was a good personal helicopter, but its looks turned away buyers lulled by style. He was right. Over the years Shark deliveries have equaled the F–28’s, notwithstanding a certification date 10 years later.

Despite being two of only a few piston models left in the market, Enstrom doesn’t see the F–28 or F280 as training aircraft. It’s not that the models aren’t well suited for it. Quite the opposite—they are incredibly easy to hover; they have a high-inertia rotor system; and, serving as a plus to many, they don’t have throttle governors. It’s simply that they’re too expensive. Both list for $485,500; compare that to an R22, which lists for $279,000 in a base configuration. The Enstroms also burn twice the fuel, although the component replacement costs are lower on a per-hour basis. The main rotor blades are good example; they last 97,500 hours on the Enstrom, compared to 2,200 on the Robinson.

Factor in this competitive gap, the need to brush up on its certification chops, and a gaping hole in the market thanks to Sikorsky’s pullback of the 300 series, and the time seems right for the TH180, Enstrom’s newest model. Announced early last year, and expected to be certified by the end of this year, the TH180 builds on many of Enstrom’s strengths, including safety and a fairly low per-hour operating cost for life-limited parts. It will retain many of the components and processes known to engineers at the company, with the exception of an added electronic governor and oleo struts—both firsts for the company. The drive system will be electrically actuated, an improvement based on customer feedback of the F–28’s manual handle (think manual versus electric flaps).

This is where the yuan really begin to roll. New aircraft programs are a vanity of new ownership, and Enstrom’s case is no different. On the scale of new certification programs, however, the TH180 is a pretty conservative bet. With Sikorsky all but out of the training helicopter business, Biegler thinks the market is there for 70 to 75 copies a year.

But new owners typically aren’t satisfied with training aircraft, especially when they are in large countries with rugged terrain and a mostly undeveloped infrastructure. Biegler admits the program is a sort of tune-up exercise. “The TH180 is almost a training program for us,” he says. “[The new owners] would much rather have a bigger product base.” If they are right about the TH180 and sales are robust, larger turbine models are a natural extension.

Which begs the question, why Enstrom? Why invest in a boutique, quirky manufacturer that was only putting out five helicopters a year? The answer is simple—knowledge and an existing production certificate. The Chongqing Helicopter Investment Company wasn’t buying a factory in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. It was buying the production certificate that factory represents, and knowledge from the people who work inside. “The Chinese are very interested in being able to understand general aviation,” Biegler said.

This is why the concern over moving Enstrom’s assets to China shouldn’t be a concern at all. If anything, observers should worry more about a venture capital firm that comes in with the singular goal of extracting profit—a move that forces cheaper labor costs. Enstrom’s value is in its engineers, sales staff, machinists, electricians, and everyone else in Menominee. While they may not make thousands of helicopters a year, those they do manufacture are well made, almost entirely in-house, by people who have been doing it for a long time.

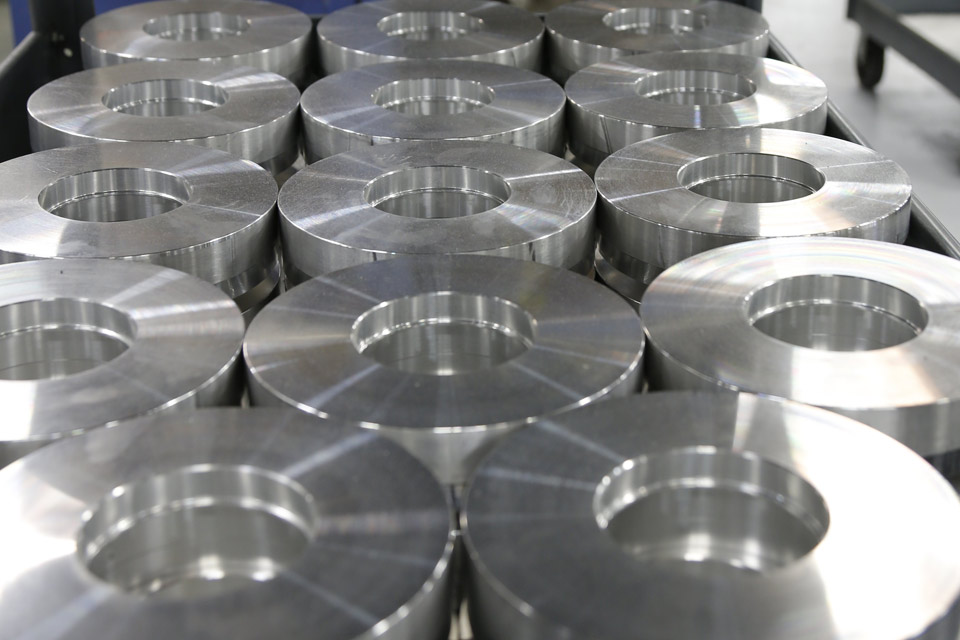

In today’s economy, most products that say “made by” actually are “assembled by.” Enstrom is an exception. About 90 percent of the helicopter is made at the Menominee facility, including all the windows and the fiberglass bodywork. Picking up and moving a production process that’s almost entirely in-house—and which takes nine months from planning to printing the airworthiness certificate—doesn’t make a lot of sense. Besides, Biegler says, the owners are proud of the “Made in the USA” label the helicopters carry.

The value of a production certificate also can’t be overstated, as it represents a significant savings of time. Any change in location would require a recertification effort with the FAA. Biegler said that if anything moves overseas, it will be in-country production for China using kits that are manufactured in the United States. “The Chinese have a desire to run their own market,” he said. That’s a model that could be replicated in other developing markets, such as Brazil and Russia. The ultimate output goal for the newly updated factory is 50 factory-built aircraft and 50 kits a year.

Enstrom’s output likely won’t ever rival Robinson’s or Bell’s, but it doesn’t have to do that in order to be successful. However much it grows, the character will remain, regardless of who signs the paychecks.

Email [email protected]

The mark of an Enstrom

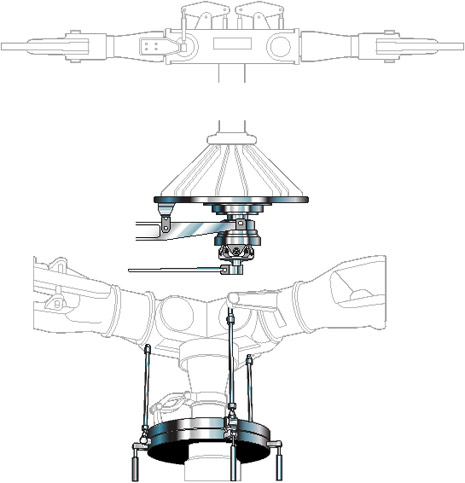

Every helicopter has to use at least a little bit of aeronautical trickery in order to fly. In Enstrom’s case, that trickery goes a step further with the main aircraft control. Helicopters turn and change altitude by changing the pitch of the main rotor blades, which is done through the swashplate. Almost all helicopter manufacturers put this swashplate at the top of the mast. Enstrom took a different tactic by placing it at the bottom of the mast, in the lower cowling. This creates a unique look that the company says is safer, but which does require a few more moving parts.

Ownership timeline

Pre-1959: Rudy Enstrom builds his first helicopter at home with no formal training.

1959: The R.J. Enstrom Corporation is formed with the support of local shareholders to build and market the helicopter.

1965: The F–28 is certified.

1968: The Purex Corporation, under the banner of Pacific Airmotive, buys the company.

1971: F. Lee Bailey buys the company.

1975: The F280 Shark is certified.

1984: Inventor Dean Kamen buys the company.

1993: The turbine- powered 480 is certified.

2000: A Swiss investment company purchases Enstrom.

2012: The Chongqing Helicopter Investment Co. becomes the new owner.

Video Extra: Take a factory tour and flight in this online video.