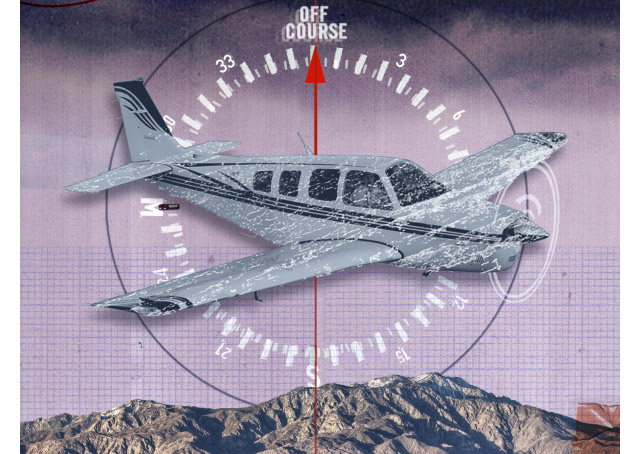

An icy encounter in the Banning Pass

My father and I, along with three passengers, were on the last leg of a long weekend trip to Baja California in February 1996. My father had bought the 1976 Bonanza A36 in 1984 and had flown N329JH extensively for more than a decade.

We cleared U.S. Customs at Calexico International Airport (CXL) without any issues. A Bonanza A36TC was parked next to us, and I asked the pilot about his intentions for the next flight. He looked at the sky, which appeared to be 4,500 broken, and said because he was going back to Fullerton, California, he would fly the southern route to San Diego and then up the coast. The mountains there were lower; on the other route, the Banning Pass between Palm Springs and San Bernardino could be rough when winter storms blew through Southern California.

My father and I discussed our flight plan. I suggested the southern route, but that would require crossing Los Angeles International Airport traffic to get to Bob Hope Airport in Burbank, so my father decided, “Let’s fly the pass.” We would take off and get an IFR clearance en route. I would fly from the right seat, and he would handle the radios.

We started the engine and I turned on the avionics. As I reached for the power switch on the Apollo GPS, my father said, “We can’t use that for IFR flight, it’s not certified; use the VORs.” So I set up for the outbound leg from the Imperial VOR and tuned the Thermal VOR on the second nav/com. I knew we would get a clearance that would take us to an intersection to avoid restricted areas to the west and north.

We took off and quickly were cleared to 12,000 feet, on the expected routing. Soon we were in solid IMC; we were flying into the teeth of a cold front.

I established my scan watching the second VOR, waiting for the upcoming intersection. Then ATC called and said to turn left immediately and intercept the Thermal VOR. We hadn’t reached the intersection; why did we have to turn? But turn I did. I twisted the OBS to the required radial and started to track on that. Probably some military traffic—yeah, that’s it.

A few minutes later we passed Thermal and started toward the Palm Springs VOR. That’s when things started to unravel.

First ATC cleared us to 14,000 feet, but we hadn’t reached 12,000 yet. The front passing over the mountains was causing a respectable downdraft on the leeward side. Even with all the power the Continental IO-520 could muster, we were barely making any progress at 11,500.

Next ATC said we were three miles right of course and instructed us to turn left and intercept the airway. Thoughts of Mount San Jacinto—taller than 11,000 feet and to the right of us—passed through my head as I took a quick glance at the windshield. Ice.

My father and I noticed the ice on the windshield simultaneously and we both reached for the pitot heat, our fingers colliding as we flipped the switch. The airspeed indicator went to zero, and I pushed down a little on the yoke to make sure we didn’t get close to stall. Now we were not climbing, and while the airspeed needle recovered quickly, the ice on the windshield was still there.

ATC called again, “Climb and maintain 14,000 and you are now left of course.” My father and I looked at each other in disbelief. The needles were centered; the gyrocompass matched the magnetic compass—something major was wrong here.

“Nine-Juliet-Hotel requests lower altitude,” my father radioed.

“Negative, climb and maintain 14,000,” ATC said.

Now we were on the west side of the pass and in an updraft. What was happening with the nav/coms? We were in IMC with mountains on either side, and who knew how much ice had accumulated on the wings?

Then a slow, deep voice called us on the ATC frequency: “OK, Nine-Juliet-Hotel, just do what I tell you. Whatever your course indicates, just turn how much I tell you and fly whatever that new course is. OK? Now turn right five degrees. Fly whatever that shows on the compass.

“OK, Nine-Juliet-Hotel, you can descend to 8,000, and turn left 10 degrees.” That deep voice sounded very reassuring.

More turns as we were vectored to intercept the Burbank ILS and then cleared to descend to 3,000 feet, all on the same frequency with the same controller. We broke out of the clouds at 4,500 feet, and there was Runway 8 at Burbank about 10 miles away.

“Nine-Juliet-Hotel has the runway in sight.”

The deep voice said, “Contact Burbank Tower, have a nice day.”

Touchdown, rollout, and park the airplane in the hangar. As the three passengers left with my father, one said to me, “I noticed you were doing the flying, nice job.” I struggled to keep from shaking when I waved back.

The next day my father flew the airplane VFR to an avionics shop in Van Nuys. The manager flew with him to troubleshoot the problem. As they taxied out he said, “There is your first problem: The mag compass is bad.” Not just bad, but 30 degrees bad. Dirt runways in Baja are not the place you would line up and check, but neither of us had bothered to check at Calexico.

In the air, the RNAV system was acting up. The power switch had failed to On, and even though we thought it was Off, it was sending spurious signals to the VORs. No wonder we were all over the sky.

Back on the ground, the manager asked why we hadn’t turned on the Apollo GPS. Yes, why hadn’t we?

My father has long since passed away, and now I own 9JH. My solution was to get an IFR-certified GPS and pitch the RNAV. Weather.gov is my most frequented bookmark, and I spend a lot of time trying to understand the weather. The only thing I forgot to do was to find out the name of that controller, so I could thank him. /p>

Jim Helsper Jr. of Rancho Palos Verdes, California, is a private pilot. He has more than 600 hours flying mostly for pleasure.

Illustration by Sarah Hanson

Digital Extra Hear this and other original “Never Again” stories as podcasts every month on iTunes and download audio files free.