Weather Watch: Icing basics—and traps

Watching out for warm fronts, and the FIKI trap

It all starts with an awareness of the three elements affecting the safety of any flight: the airplane, the pilot, and the environment. In the icing season, an “ideal” airplane will have enough power, fuel capacity, ceiling, and equipment to let its pilot circumnavigate areas forecast to experience icing conditions—and escape them should there be an inadvertent encounter. And let’s be clear—you should take action to exit icing conditions at the first sign of ice. It’s wise to look at small-radius objects like rivet heads, antennas, wing struts, or hand grips. That’s where the first signs of icing show up.

The pilot should know how to obtain icing airmets and other information so that ice-free routes can be planned, and a proper go/no-go decision can be made. One of the best sources are the current and forecast icing potential (CIP and FIP, for short) pages on the Aviation Weather Center’s website. Here, under Forecast Icing, you’ll see drop-down menus that let you locate levels of icing severity (and their probabilities) at altitudes from the surface to 29,000 feet, and forecasts out to the next 18 hours. Another panel shows the lowest freezing levels for the next 18 hours, another shows icing sigmets, and yet another posts icing pireps. Other valuable tools include the site’s G-airmet page where you can see a 12-hour graphic depiction of anticipated icing coverage, in three-hour intervals.

Any briefing should, of course, also include METARs and TAFs for your route—for both destination and likely alternate airports. What you’re looking for are low cloud tops and high cloud bases, with above-freezing temperatures in the lower levels of the atmosphere. Should you inadvertently encounter ice, you want it to melt as you descend, and most certainly want to be ice-free for any instrument approaches.

Problems crop up fast when the rain becomes supercooled as it falls into the cold air mass.The icing environment is a complicated subject, and volumes have been written about it. Simply put, you can expect icing in any clouds, precipitation, or visible moisture (defined in terms of surface visibility as one statute mile or less) where freezing temperatures coexist. Some manufacturers recommend turning on pitot heat and other anti-ice equipment at outside air temperatures of plus-five, or plus-10 degrees Celsius for an extra measure of safety. You can expect the worst icing in systems over the Great Lakes, New England, and the Pacific Northwest, where large bodies of water help impart extra moisture to low pressure systems that already involve the vertical transport of colder air at those latitudes.

Avoid any fronts or lows in the winter months because they all involve rising air masses, and usually bring extensive cloud formations. A quick look at satellite imagery will give you an idea of the extent of cloud coverage; on infrared satellite views, the highest cloud tops will appear brightest.

Here are some important items, and traps, to bear in mind this winter:

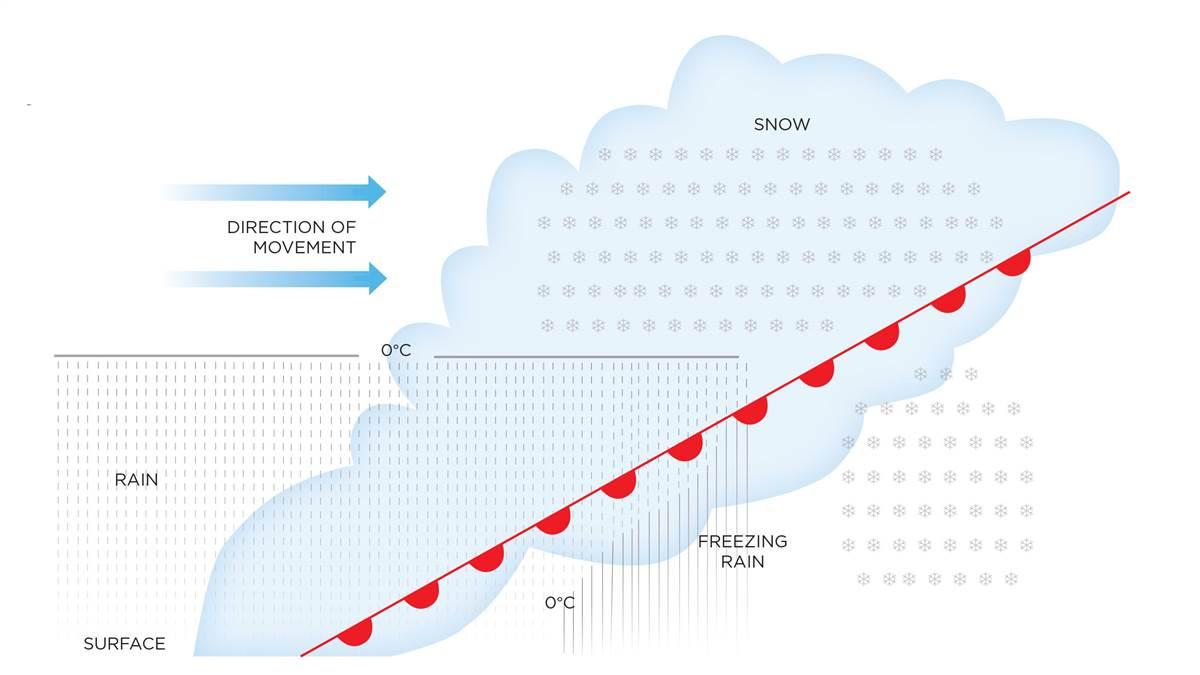

It’s just rain. Let’s say you are instrument-rated and current and are flying in light rain. It’s tempting to believe that the rain will persist, but you may be flying in a temperature inversion. This occurs when flying at lower altitudes below a warm frontal surface. The advancing warm air rides up and over a retreating cold air mass, causing rain to fall. Problems crop up fast when the rain becomes supercooled as it falls into the cold air mass. Clear icing or freezing rain may soon be in the offing.

No problem, I have datalink Nexrad imagery. Nexrad does a great job showing areas of precipitation, and the bigger the droplets, the brighter the radar returns. But Nexrad does not show clouds, so it’s of little use in avoiding most icing conditions.

It’s OK, I’m on top. That’s a nice place to be, but eventually you’ll descend for a landing. And it had better be at an airport not affected by icing conditions. Otherwise, a descent through a cloud layer—or layers, if you’re between layers—could mean that you’ll pick up ice on the way down.

My airplane has FIKI certification. Having Flight Into Known Icing-certified ice-protection equipment is reassuring, but it’s not capable of handling severe icing conditions such as freezing rain, freezing drizzle, supercooled large droplet (SLD), or mixed icing conditions that result in ice buildups exceeding the capability of the system—or ice formations aft of protected surfaces. How do you know when your airplane is in conditions worse than those used in FIKI certification tests? Visual cues include ice forming aft of protected surfaces such as wing leading edges, ice building up at the corners of the windshield, and ice forming on engine nacelles and propeller spinners farther aft than normally observed.

Large, powerful, FIKI-certified Transport category airliners have been brought down by SLD and other severe icing types. Think of FIKI approval as a very helpful escape tool—and under no circumstances think of it as carte blanche permission to indefinitely remain in icing conditions.

Email [email protected]