Weather: Getting battered

Bad byproducts of a thunderstorm

The largest hailstone recorded in the U.S. fell near Vivian, South Dakota, in 2010. It was eight inches in diameter and almost two pounds.

Hailstones are a sign of an even greater danger of thunderstorms: strong up- and downdraft winds that create extremely violent turbulence.

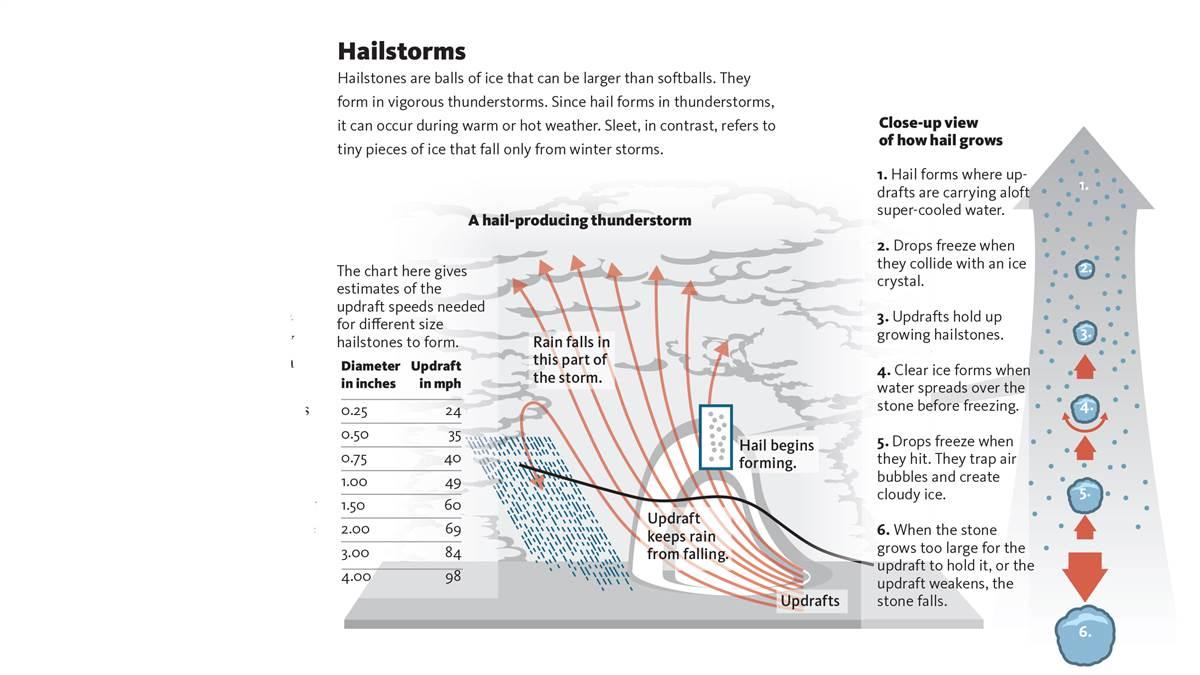

To create hail, a thunderstorm has to be producing strong updrafts as shown on the right side of the illustration on page 45. Meteorologists don’t routinely measure the speeds of thunderstorm updrafts, but researchers can calculate the possible highest speeds of updrafts and downdrafts that a particular thunderstorm is likely to produce. The chart on the lower left side of the figure shows the calculated updraft speeds needed to create hailstones of different sizes.

As a general rule, the speeds of thunderstorm downdrafts are half the speed of its updrafts. For example, a thunderstorm producing three-quarter-inch hail has 40-mph updrafts and 20-mph downdrafts. If you fly into the storm you could run into 20-mph downdraft and then immediately into a 40-mph updraft, or the other way around. Such differences in the velocity of streams of air close to each other would create a “bump” you won’t forget.

ABSENCE OF HAIL DOESN’T MAKE A THUNDERSTORM A SOFTY. Meteorologists estimate that 10 percent of all thunderstorms produce hail. As a thunderstorm moves through the sky, hail will be falling from a small part of it, creating a swath about 10 miles long and a mile or two wide. Some hailstorms have left a 100-mile path up to 10 miles wide.

This means that although large hailstones are one measure of the violence occurring inside a thunderstorm, the apparent lack of hail doesn’t mean a thunder-storm couldn’t shake the fillings out of your teeth.

THE LIFE STORY OF HAIL. Avoiding hail begins with knowing what it is, what conditions create it, and how it acts.

A hailstone begins as a small piece of ice, either a frozen raindrop or a snow crystal, in a thunderstorm updraft. To grow into a hailstone, the embryo needs to be the right size for the speed of the updraft.

Everything has a terminal velocity—the highest speed at which it falls based on its size and shape and the resulting aerodynamic drag. To grow, a hail embryo must have a terminal velocity that is less than the updraft’s speed so that small drops of liquid water stream past it, with a few hitting the embryo and freezing onto it.

The water drops have to be supercooled—that is, colder than 32 degrees Fahrenheit, but still liquid. Such supercooled water drops instantly turn to ice when they hit anything, such as a hailstone embryo, a hailstone, or your airplane. (If you’re in a thunderstorm, airframe icing is probably the least of your worries.)

As more drops hit the embryo and freeze, it grows, increasing its terminal velocity. If the updraft supporting the hailstone slows or stops, the stone falls. Very strong updrafts can toss hailstones out of the top of a thunderstorm.

This creates an additional hazard for pilots: Hailstones can come out of the clear sky around a thunderstorm where they’ve been tossed. Hailstones sometimes fall from the anvil cloud, which streams downwind from the top of a powerful thunderstorm. That’s a good reason not to fly under such anvils.

As a rule, pilots of all levels of skill and experience—and in any kind of airplane—should always avoid thunderstorms. Stay at least 20 miles away from any thunderstorm that could be producing hail. In fact, staying 20 miles away from any thunderstorm is a good idea because you can’t look at a storm and tell whether it’s producing hail.

The good news is that most of the reports of hail encounters say the airplane landed safely, sometimes with damage such as the leading edges of the wings looking like someone had hammered on them.

A few reports, however, leave no doubt that pilots shouldn’t mess with hail. A National Transportation Safety Board report of the 1986 crash of a Cessna 177RG Cardinal in Texas notes that the airplane’s windshield separated from the airplane after hail struck it. This probably incapacitated the pilot, the NTSB said, but that likely made little difference. Cessna engineers told the NTSB that with the windshield gone, the airplane probably was not controllable.

HAIL SIZE TO MAKE A THUNDERSTORM ‘SEVERE.’ You might recall reading or hearing that winds faster than 58 mph, the presence of a tornado, or hail larger than three-quarters of an inch are the criteria for the National Weather Service to classify a thunderstorm as “severe,” which means the NWS issues special warnings for it. Many aviation texts include this definition of a severe thunderstorm.

But, on January 5, 2010, the NWS changed the hail size to classify a storm as severe from three-quarters of an inch (the size of a penny) to one inch (the size of a quarter.) The NWS had found that storms that met the earlier hail standard seldom produced the damaging winds associated with severe thunderstorms. In other words, it led to severe thunderstorm warnings that were false alarms.

Nevertheless, when you are piloting an aircraft, any signs or reports of hail is another reason for staying at least 20 miles away from the thunderstorm.

Jack Williams is an instrument-rated private pilot and author of The AMS Weather Book:The Ultimate Guide to America’s Weather.