Sign here

The two regulations that detail mechanic endorsements

Dick is the maintenance officer of an 80-member flying club in northern New Jersey. The club operates several aircraft, including a 2011 Cessna Skyhawk SP powered by a Lycoming IO-360-L2A engine. The engine has reached 2,400 hours—400 hours beyond Lycoming’s published TBO of 2,000 hours. At the Skyhawk’s recent annual inspection, the four-cylinder Lycoming had compressions in the high 60s and low 70s. It wasn’t using much oil. The oil filter was clean, and the oil analysis report had no red flags.

Most experienced A&Ps would agree that the parallel-valve four-cylinder Lycomings are the most bulletproof piston engines in general aviation, and that the Lycoming IO-360-L2A is the best of the breed. If flown frequently and regularly, they often make it to 4,000 hours or more between overhauls.

The flying club’s shop in New Jersey didn’t see it that way. Although mechanics at the shop signed off the Skyhawk’s recent annual inspection as airworthy, they made it clear to Dick that they were profoundly uncomfortable with the club continuing to operate the engine beyond TBO. Dick, who had done his homework, told the shop that the club wanted to continue operating the engine, monitoring its condition with 25-hour compression checks, borescope examinations, and oil filter inspections.

The people at the shop made it clear they weren’t interested: “The next time you bring the airplane in for an oil change, we won’t be able to sign it off.”

Can a mechanic withhold his signature?

Any A&P who withholds his signature from an aircraft’s maintenance records (or even threatens to do so) is acting improperly and in contravention of the federal aviation regulations. The regs do not permit any mechanic or shop to ground an aircraft or hold it hostage in this fashion.

You might well be asking yourself, How can this be? Doesn’t a mechanic have the right to decide whether he is comfortable signing off a maintenance logbook entry approving an aircraft for return to service? Surely a mechanic is not compelled to sign off an aircraft that he doesn’t consider airworthy. If a mechanic didn’t have that discretion, wouldn’t his signature become meaningless?

Indeed, this is such a confusing issue that it confounds plenty of A&Ps. But the FARs are clear and unambiguous on this point: If a mechanic works on your aircraft, he is required to make and sign a logbook entry documenting his work. That’s true whether or not the mechanic believes your aircraft is airworthy.

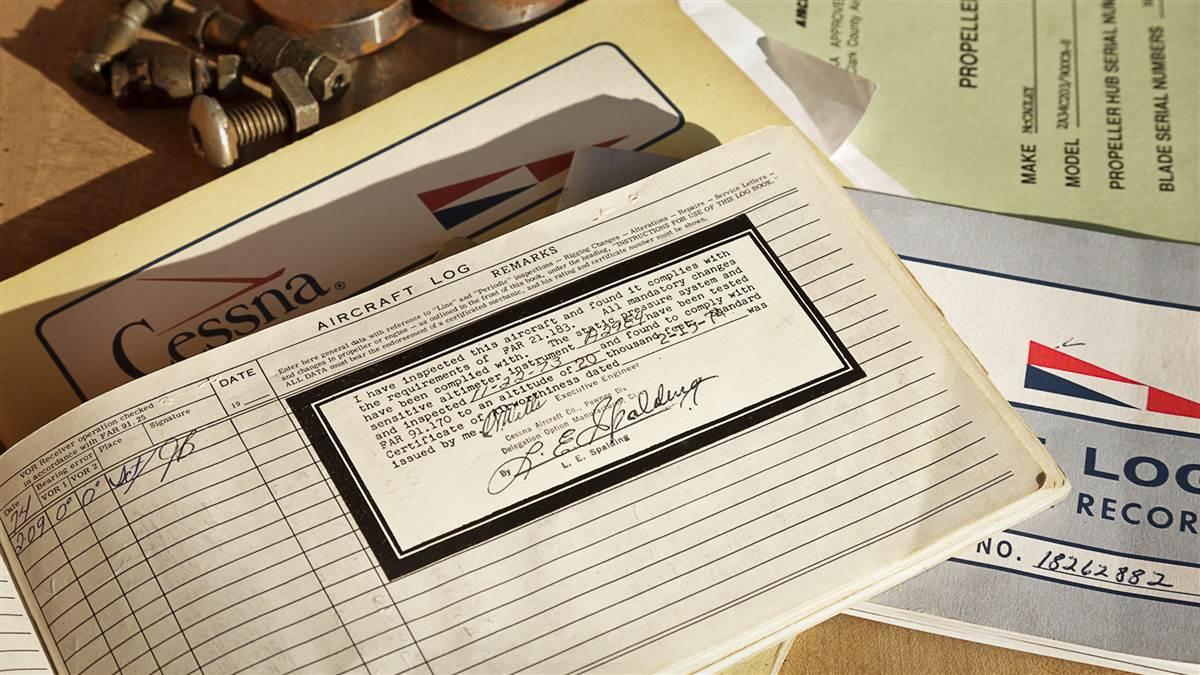

Two rules govern maintenance records and sign-offs. FAR 43.11 deals with records of inspections (such as annual inspections), and FAR 43.9 deals with records of all other kinds of maintenance (such as preventive maintenance, repairs, alterations, and overhauls). One reason for these two different rules is that the meaning of a mechanic’s signature in a 43.11 inspection logbook entry is entirely different from the meaning of a mechanic’s signature in a 43.9 noninspection logbook entry. Both mechanics and aircraft owners need to understand this difference clearly.

Signing off inspections

If you put your aircraft in the shop for a required inspection (say, an annual), then 43.11 applies. The inspecting mechanic is required to examine the entire aircraft from wing tip to wing tip and spinner to tailcone, and must verify that it meets “all applicable airworthiness requirements.” He must verify that the aircraft complies with its type design, is in condition for safe operation, and complies with all applicable ADs. If it’s a piston aircraft, he must run up the engine and verify that critical engine operating parameters fall within prescribed limits. Then, if no unairworthy items have been found, he must make and sign a logbook entry that says, “I certify that this aircraft has been inspected in accordance with an annual inspection and was determined to be in airworthy condition.”

But what if the inspection uncovers one or more discrepancies that make the aircraft unairworthy? And what if the owner is unwilling to have those discrepancies repaired? Can the inspecting mechanic simply refuse to sign the maintenance record entry and hold the aircraft hostage until the owner cries “uncle”?

No, he can’t. FAR 43.11 provides guidance to the mechanic who finds himself in this situation. It requires the mechanic to “sign off the inspection with discrepancies” as follows: “I certify that this aircraft has been inspected in accordance with an annual inspection and a list of discrepancies and unairworthy items dated [date] has been provided for the aircraft owner or operator.”

The mechanic then hands the owner a signed-and-dated list of airworthiness discrepancies found during the inspection. At that point, the annual inspection is complete and the inspecting mechanic’s job is done. His signature disapproving the aircraft for return to service attests (at least in theory) that every atom and molecule of the aircraft is airworthy except for the items on the discrepancy list he handed the owner.

The owner must correct those discrepancies before the aircraft may flown. He is free to have them corrected by any mechanic he chooses. There’s no need for the inspecting mechanic to look at the aircraft again. The next annual comes due in 12 calendar months.

In short, a mechanic performing a required inspection (e.g., annual or 100-hour) is always required to make and sign a logbook entry memorializing the inspection, but he may sign off the aircraft as either airworthy or unairworthy. If he signs it off as airworthy, he approves it for immediate return to service. If he signs it off as unairworthy, he gives the owner a list of discrepancies to be corrected. Either way, his job is done.

Signing off other maintenance

Dick’s shop had signed off the aircraft as airworthy at the last annual inspection. Now they were saying they couldn’t sign off the next oil change. Since that’s a non-inspection preventive maintenance task, the rules of FAR 43.9 would apply to that logbook entry.

FAR 43.9 requires the mechanic to make a maintenance record entry that includes a description of the work performed on the aircraft, the date it was completed, the name of the person who performed the work—and, “If the work performed on the aircraft…has been performed satisfactorily, the signature, certificate number, and kind of certificate held by the person approving the work. The signature constitutes the approval for return to service only for the work performed.”

Those two sentences bear careful reading. The first sentence makes it explicitly clear that a mechanic’s signature on a 43.9 logbook entry does not signify anything about the airworthiness of the aircraft. It signifies only that the work the mechanic completed was performed satisfactorily. In fact, the only basis on which a mechanic could legitimately withhold his signature from a 43.9 logbook entry would be if he took the position that his work was performed unsatisfactorily—in which case, presumably, he would be obligated to redo it in a satisfactory fashion.

The second sentence makes it clear that the mechanic’s signature does not constitute an approval for return to service for the entire aircraft (the way an annual inspection signoff does). It constitutes approval only for the work the mechanic performed.

Here’s the example I use to clarify this point when I teach IA renewal seminars: Imagine that an owner brings his airplane into your shop. It has two obvious airworthiness discrepancies: The right main landing gear tire is flat, and the left wing is missing. The owner asks you to change the flat right main landing gear tire. Can you do so and then sign off the logbook entry?

The answer is yes. The mechanic certainly can change the flat tire. Having done so, he is obligated to document his work in a 43.9 logbook entry and sign it off. His signature in the logbook does not imply that the left-wingless airplane is airworthy, only that the tire change was done in a satisfactory fashion. The owner hired him strictly to change the tire, not to inspect the rest of the aircraft.

A conscientious mechanic would say, “I couldn’t help but notice that your airplane’s left wing is missing, and I recommend you don’t try to fly the airplane in that condition.” But the mechanic can’t refuse to sign off his work. The decision whether to fly is the owner’s, not the mechanic’s.

So if an A&P works on your aircraft and makes noises about “not signing off the aircraft” unless you consent to letting him do work that you don’t want done, print out a copy of FAR 43.9 and walk him through it. The reg is clear: If a mechanic performs work, he is obligated to make—and sign—a logbook entry describing that work.

Mike Busch is an A&P/IA.

Savvy Maintenance coverage sponsored by Aircraft Spruce