Airbus tech powers USA racing yacht

Pierre-Marie Belleau, the head of Airbus business development, said the size and the shape of the Oracle yacht’s dual wings have “huge similarities” to an Airbus jetliner wing. Their profile looks like the silhouette of an A320 wingtip “sharklet.”

“In sailing conditions, the top of the sail wraps in a different direction [than the bottom] and creates additional force on the opposite side of the boat, which helps stability,” said Belleau. “It’s quite a different phenomenon and we can measure that very accurately to give us a much better understanding” of the trade-off between the wing providing speed and power, and the drag caused by twist.

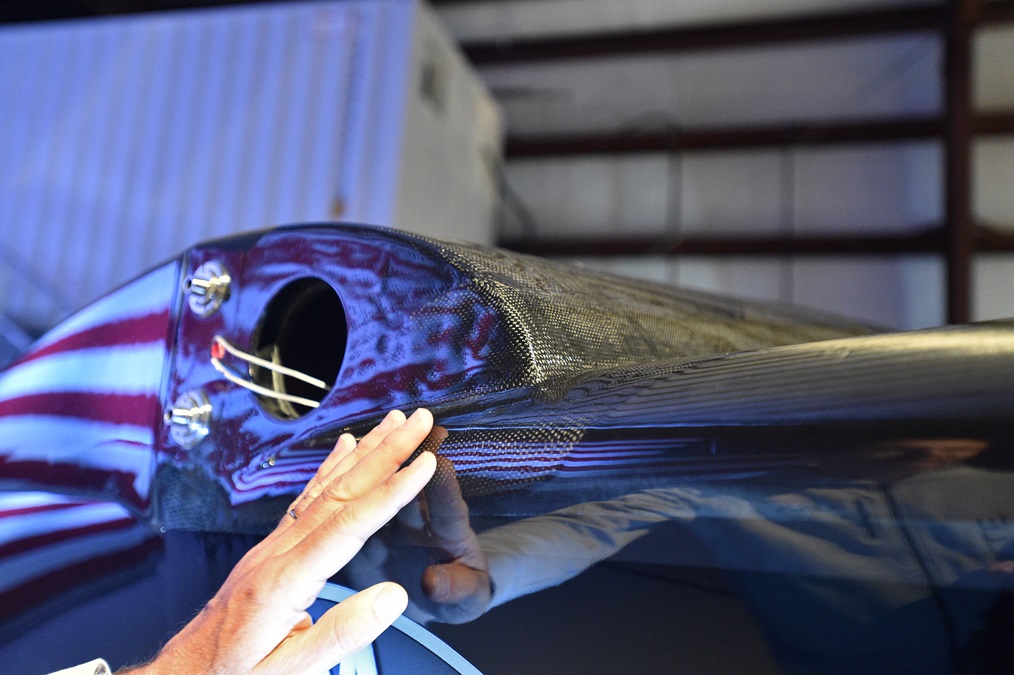

The main element of the seven-story-tall sail wing is shaped like a "D" at its leading edge and is covered with “sort of a shrink-wrapped membrane,” explained Belleau. “The second element is on hinges and is controlled by hydraulics,” similar to an airplane flap in that both change the shape of the wing. By applying varying hydraulic pressure to three sets of trailing flaps, the overall sail contour can be adjusted to a particular shape depending on weather conditions. “The guys can change the wing camber all the time.”

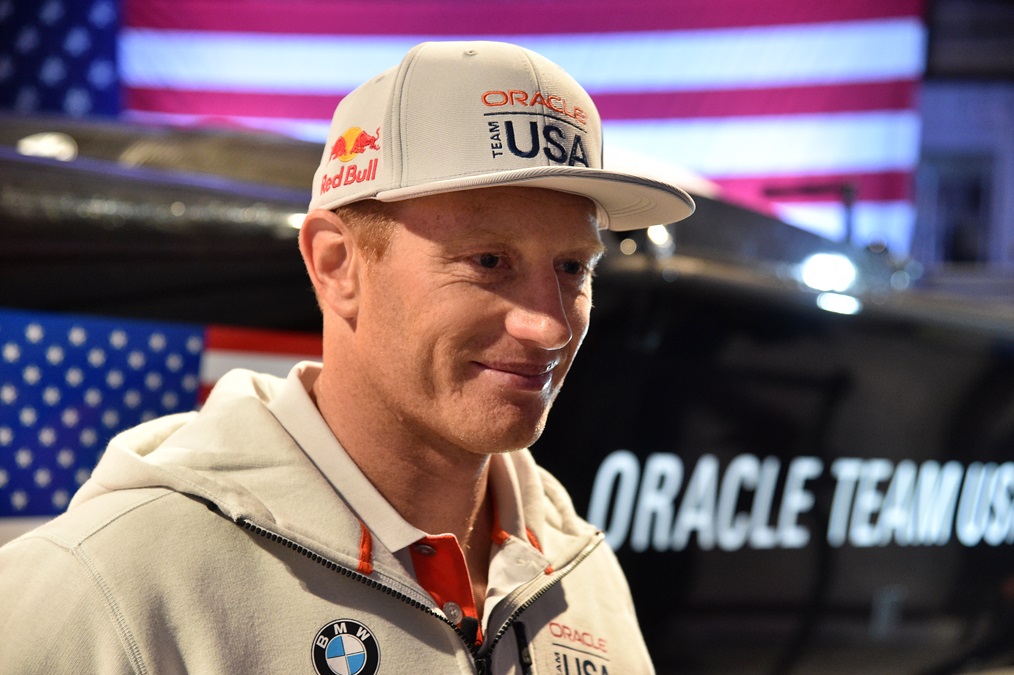

“Just like an airplane landing, we want to get a really high lift coefficient and generate more force and we’ll put that flap at a really high angle, pretty much like an airplane landing,” said Ian “Fresh” Burns, Oracle Team USA’s director of performance. “If we can get a high angle of attack, we can generate more force and get more energy into the boat and go faster. It’s very similar to an airplane wing. In fact, it looks just like an airplane wing with maybe a little bigger flap and a little bit smaller main element.”

The "sharklet" foil wings fly just above the water and are “moving all the time” said Burns, as are the rear elevators, which extend into the water. “Good design means less energy wasted. We have rams, we have pumps, we have tubing” to help push fluid to where it needs to be. “The more drag you have, the slower you go.”

Spithill and his crew constantly manipulate the devices to harness wind energy and turn it into power and speed.

“Most airplanes if you let go of the stick you’ll go straight,” said Burns. “If you let go of the stick on our boat it’ll do a wheelie.” Burns said the yacht is “on that middle ground where you need the input from a skipper because the two key ingredients are how fast his reactions are and how good the control system is.”

When the horizontal wing airfoils were adopted, he estimated that the ships initially flew above the water about 50 percent of the time. With experience that figure rose to 80 percent fairly quickly “and now we’re up to 90 percent flying,” said Burns. It’s now likely “we can fly the whole race, 100 percent of the time,” but not without “a great control system and a crew that can handle it.” The boats “travel very fast, about 30 knots upwind and about 35 to 40 [knots] downwind.”

A month of America’s Cup sailing commences in Bermuda May 26 with teams from France, Great Britain, Japan, New Zealand, and Sweden battling to face the Oracle Team USA defenders beginning June 17. Airbus provided a dozen journalists with an advance look at the engineering that will be on display during the event. According to Spithill, Belleau, and Burns, the crew that touches the water first will likely lose the race.

“The Americas Cup is always a race for the best technology,” said Burns, “and whoever has the best, wins.”