Weather: Hidden potential

Are strong storms brewing? 'CAPE' measures atmospheric instability

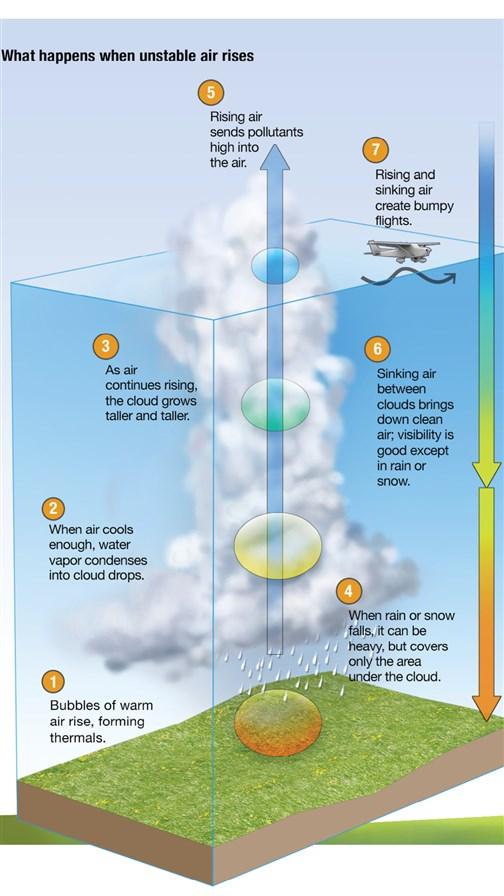

Thunderstorms are made of unstable, warm, rising and falling air; cumulonimbus clouds; precipitation (heavy rain or ice in the form of hail); and lightning and thunder. Any thunderstorm is a threat to aircraft—which is why the FAA advises staying at least 20 miles away from thunderstorms.

The faster and higher the air rises, the more powerful the thunderstorm will be. The speed of the rising air, in turn, depends on the temperature difference between the rising air and the air it’s rising through. The greater the difference, the faster the air rises.

While various measurements of thunderstorm strength—such as convective outlook, the K-index, and lifted index—have been used in the past, the most common one used today is convective available potential energy (CAPE). CAPE is a measure of the potential energy available in the atmosphere up to 40,000 feet that can power thunderstorms. It doesn’t say whether that day’s thunderstorms will tap all of the potential energy, but it’s a good measure of the potential danger.

You are likely to see CAPE mentioned if you read the technical discussions from the National Weather Service Storm Prediction Center or local weather service offices when severe thunderstorms or tornadoes are possible. In general, CAPE values of less than 1,000 joules per kilogram represent weak instability, 1,000 to 2,500 J/kg moderate instability, 2,500 to 4,000 J/kg strong instability, and more than than 4,000 J/kg extreme instability.

Meteorologists estimate the fastest possible thunderstorm updrafts by multiplying CAPE by two and taking the square root of the answer for updraft speed in knots. In other words, if the CAPE is 3,000 joules per kilogram, you could expect updrafts of approximately 77 mph. This is a rough guess, but it gives you an idea of how violent thunderstorms can be.

Another rule of thumb is that a thunderstorm’s downdrafts will be about half as fast as the updrafts—in this case, 38 mph. Imagine flying into a 38-mph downdraft and then seconds later into a 77-mph updraft. That is a wind shear of 115 mph—enough to throw even a large aircraft out of control.

Even if the CAPE were only 500, you wouldn’t want to fly into or very close to any growing cumulus clouds. The updraft speed could be in the range of 32 mph and downdrafts of around 16 mph, which would give you an extremely bumpy ride.

You will likely have a smoother ride if you climb above the tops of any puffy clouds in the sky. The clouds top out where the rising air is no longer warmer than the surrounding air—thus, no longer rising.