Flying the Garmin G3X Touch

Who would have guessed that a rather tired looking 1970s Grumman Tiger would be the poster child for a new generation of avionics designed to bring new levels of safety and reliability to the legacy fleet? And, yet, there it is in front of me, bristling with colorful presentations on three glass displays: primary flight display with synthetic vision, a multifunction display with electronic engine gauges, and a backup battery-powered display with enough information for you to fly safely for hours should all the rest of it give up the ghost.

The Garmin G3X Touch is not the first non-TSO’d cockpit suite to be approved for use in certified airplanes, but it is the one that is available on the most models—nearly 500 with more in the works. The Kansas manufacturer announced the approvals in March, showed off the Tiger at the Sun 'n Fun International Fly-In and Expo in April, and provided us the chance to fly it a few weeks later from their R&D hangar at New Century Aircenter in Olathe.

Whereas most avionics and such gear in production airplanes is built to minimum performance standards that meet technical standard orders (TSO), systems for experimental aircraft have no such official threshold. That doesn’t mean the experimental gear isn’t tested nine ways to Sunday, it just means that the manufacturer doesn’t have to demonstrate the same level of performance as it does for equipment destined for a certified aircraft. All of that official testing and related documentation adds greatly to the cost and doesn’t necessarily add a lot to safety or reliability. The result is significantly greater cost for TSO’d gear versus non-TSO’d. And without the constraints of a TSO process, a manufacturer can be much more nimble in introducing new features and capabilities while quickly resolving issues as they are discovered without having to jump back through all the certification hoops. The result is the amazing capabilities and ever-evolving features of the panels in experimental aircraft.

Recognizing the need for cost-effective and safety-enhancing upgrades to the legacy fleet, AOPA in 2015 started working closely with the FAA, manufacturers, and other aviation associations to create new certification pathways to bring non-TSO’d systems into certified airplanes. The result has been a flood of new products at more affordable prices. These new products are still certified; it’s just the pathway to demonstrate compliance that is different.

Garmin’s foray into the non-TSO’d space was the G5, which it got approved for certified aircraft in 2016, only a few months after it was introduced for experimental aircraft. The little display includes its own solid state gyro—an attitude heading reference system (AHRS) and presents for the pilot attitude information, airspeed, altitude, yaw, and a host of other data. At the twist of a knob it can reconfigure itself to be a horizontal situation indicator (HSI). It comes with a four-hour battery.

The G3X Touch is Garmin’s first large-screen non-TSO’d system for production aircraft. It can be as simple as a single seven-inch display set up as a primary flight display (PFD) that can be configured as a multifunction display (MFD) and engine indicator display with the optional sensors tied in. Most, however, will want more display options, which was demonstrated in the Tiger we flew. Front and center there is a 10.6-inch screen that can be divided into a dizzying array of displays and inset windows—PFD, MFD, engine gauges, moving maps, traffic displays, weather, flight plans, you name it. I think I saw a scrolling recipe for Chicken Marsala on there at one point in our flight.

To the right is a seven-inch display with the same capabilities. Both include AHRS, making for an easy backup should one or the other fail. Further backing it up is the G5—to the left of the big display, with its own AHRS and four-hour back-up battery. Yes, a 40-plus-year-old single-engine piston airplane with triple redundant AHRS. Further enhancing safety is the non-TSO’d GFC 500 digital autopilot. The AHRS in any one of the displays can drive the autopilot, as demonstrated by Jessica Koss, Garmin’s aviation media relations specialist and a CFII. While I flew she first failed the large display. She then re-engaged the autopilot and all was well. Then she failed the seven-inch display. The touch of a button brought the autopilot back online, driven by the G5.

Under such an architecture, if you end up in a situation where you have to hand-fly during an emergency, you’re having a very bad day.

On the G3X Touch display, a touch of any field brings up a large window in which you enter information. Touch the altitude display window, for example, and you can easily enter an altitude for the autopilot to climb or descend to. If you’re a knob person, there are concentric knobs for that too. The autopilot comes with complete envelope protection and Garmin’s ESP—electronic stability and protection, which attempts to keep the airplane safely near the middle of the flight envelope even when the autopilot is off.

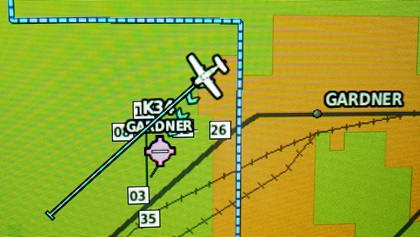

While the user interface will be familiar to anyone who has flown other Garmin products, the panel includes several features not available in the company’s higher end TSO’d boxes. Most notable is a subtle line of arrows on the MFD continuously flowing toward the nearest airport that is within gliding range. On the bottom of the PFD a field provides the identifier, distance, and direction to the nearest airport, even if it is outside of gliding range.

As with any other product line—TSO’d or non-TSO’d—in order to fly instrument approaches, the displays must be connected to a TSO’d navigator. In this case, the Tiger has a GTN 650, which we used to fly a visual approach procedure back to Runway 36 at New Century. But Garmin’s new lower cost GPS 175 or GNX 375 would fit the bill as well. The displays also interface with and control a variety of Garmin nav/com radios, showing frequencies and station ID at the top of the screens. The system also interfaces with the Garmin Connext system that allows wireless transfer of GPS position, weather, traffic, flight plans, and other data between the panel and a variety of apps on handheld devices.

List prices for the G3X start at $7,995 for the seven-inch display and $9,995 for a 10.6-inch display; each includes the install kit, GPS antenna, AHRS, and magnetometer. However, if you buy the two together, the price totals $14,865. A four-cylinder engine system adds about $3,000 to the price.

Koss says the system is designed for use in Class I airplanes—those of 6,000 pounds or less—and ones that include other panel products in the “Garmin ecosystem.” Those with heavier airplanes or products from a variety of manufacturers will need to consider the Garmin G500 TXi or G600 TXi panels, which include many more input/output options for products from other manufacturers. The G500 TXi starts at about $12,000.