Proficient Pilot: On edge

In the company of COVID-19

Not so much now, though.

My son Brian, an Airbus A321 captain for American Airlines, told me what it has been like to fly in the company of COVID-19. Emptiness seems to best describe it. Empty airways. Empty airplanes. Empty airports. Empty terminals—you can’t even buy a cup of coffee.

One of his flights had only 28 passengers, and there were that many only because the two previous flights had been canceled. On some flights there are more flight attendants than passengers. Flight attendants are on edge, unable at times to maintain social distancing, hoping not to hear a cough or a sneeze. A newly hired flight attendant had just begun her dream job, but her enthusiasm has been dashed; she can’t wait to be furloughed.

Brian says that in his 31 years as an airline pilot, he has never seen lavatory soap used up so quickly—or at all—much less by so few people. At the end of three days of flying, his hands are raw from so much washing and disinfecting (hand sanitizers are everywhere). A rule regarding oxygen masks has been changed for the time being to reduce the chance of infectious disease being passed from one pilot to another. When above 25,000 feet, a pilot is no longer required to don an oxygen mask if the other pilot leaves the cockpit.

At some layover hotels, the only guests are crewmembers. Their rooms are sterilized prior to each check-in. Each room is provided with only one roll of toilet paper. The restaurant is closed, and prepackaged food is handed out from behind the reception counter.

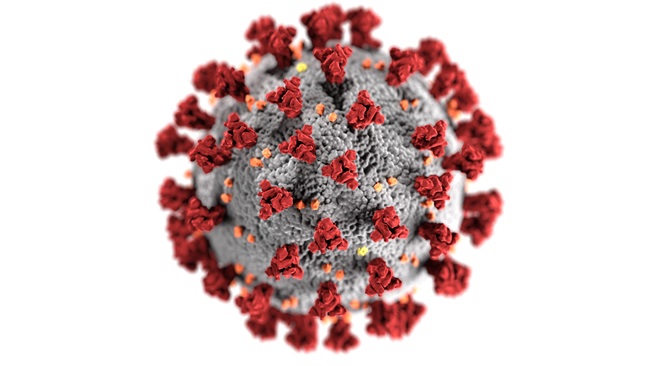

I climb as steeply as the 180-horsepower engine will allow, each second taking me higher and farther from the threat of those invisible microbes.When a portion of an air route traffic control center is closed by the virus, pilots can expect complex clearances and tortuous routings at undesirable altitudes. Flight times and fuel burns can be increased dramatically—a challenge to planning. Control towers are occasionally shut down as well, forcing pilots to deal with CTAF and landing at nontowered airports. That’s no big deal for lightplane pilots but is a first for many airline pilots, who might find the experience a bit nerve-wracking. During Brian’s flights, the control towers at New York’s JFK, Chicago’s Midway, and Las Vegas had been shut down by the virus.

He says that it has become increasingly more important not to allow yourself to become distracted by depressing thoughts and events. He and his first officer need to concentrate more than usual on flying the airplane. “The best way to cope,” he says, “is to maintain a sense of humor, although sometimes the laughter seems forced.”

Pilots work with the incessant fear of contracting the virus and bringing it home. Brian wonders if it will be safe to hug his wife when he gets back. Should they share the same bed or bathroom? When he hears about various ATC facilities shutting down because of a controller testing positive, he wonders if he’ll get home at all. Upon completion of a flight assignment, Brian usually looks forward to his next flight, but not now. He would much rather stay home with his family.

This clearly explains why I am currently content with not being an airline pilot. I am, however, thrilled to be a general aviation pilot. I relish being able to shed my mask and surgical gloves as I climb aboard the family Citabria to escape the misery defining our lives these days. Taxiing out feels strange. Camarillo, my home airport, is lonely, reminiscent of an early morning departure on Christmas day.

I climb as steeply as the 180-horsepower engine will allow, each second, every minute taking me higher and farther from the threat of those invisible microbes. There are small cumulus clouds remaining behind a recent cold front, and I joyously nip at their edges—within legal limits, of course—and experience the exhilaration and happiness that the virus has stolen from us. I have always considered the sky to be Nature’s (or God’s) palette, and on this day Her (or His) artful creations are especially magnificent. It is glorious. Fresh, clean air from the vents washes over me and is invigorating. A limited fuel supply compels a return to reality and the imprisonment imposed by the virus.

This local flight revitalized and reminded me that the general aviation airplane—large or small—is one of America’s great enablers of freedom.