VFR Unleashed: Glad I called a briefer

Part 10 of a multi-part series on expanding our horizons as VFR-only pilots

One of the most enjoyable aspects of VFR flight is the freedom to fly wherever we want, whenever we want, without talking to anyone. While there are several obvious qualifiers of various airspace and weather limitations, the freedom to fly on our own and not engage the air traffic control system is something truly unique to U.S. aviation and VFR flight.

Many VFR pilots spend most of their flight time in Class E or G airspace where the requirements to talk to ATC are minimal if not entirely nonexistent. Even radio communications in the traffic pattern at nontowered airports—though strongly recommended—are not mandatory. While we all had to demonstrate a certain proficiency interacting with ATC to earn our private pilot certificates, for some VFR pilots that demonstrated proficiency may have been one of their last visits to a Class D airfield and perhaps quite some time ago.

But ATC and other communications systems such as flight service are there to help us make flying safe, efficient, and enjoyable. Regardless of where you fly most often, becoming comfortable with routinely checking in with ATC or flight service is a valuable asset.

That skill set might even keep you out of trouble someday. It did for me.

When I landed at Greater Cumberland Regional Airport in central Maryland, one beautiful summer afternoon, I had not a care in the world. Following the Potomac River turn by turn along its twisting route from my home airport, Leesburg Executive Airport in northern Virginia, made for a fun, relaxing hour of aviating.

That fun came to a screeching halt when I heard my tail number being called over the airport loudspeaker.

“Will the pilot of [N12345] please report to the airport manager’s office,” I heard as I walked inside to find the snack machine. “This can’t be good,” I thought to myself.

I poked my head into the airport manager’s office. A polite lady informed me that, “Washington Center is on the phone for you.”

“This really can’t be good,” I said to her out loud.

When I answered the phone, I was met with a curt request for my pilot certificate number. After a few questions about my identity, the controller informed me that I had been tracked violating Prohibited Area P–40 around Camp David, the famed U.S. presidential mountain retreat center.

I was stunned. I stammered a bit with inquiries about whether the prohibited airspace was significantly larger than usual, or if she had tracked the right aircraft, or how she had determined I was the guilty radar target.

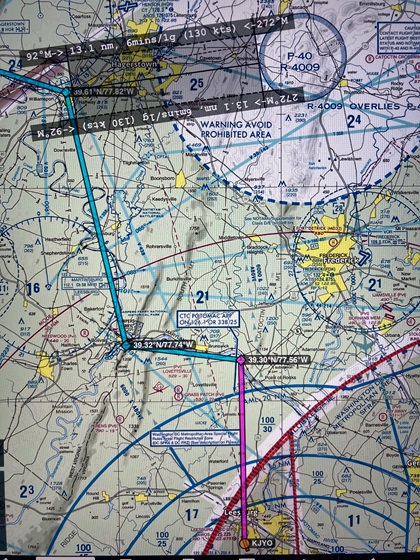

I knew the airspace well (you don’t fly around Washington, D.C., without knowing about P–40), and I knew for certain I had been nowhere near it. I had departed Leesburg, immediately intercepted the route of the Potomac River, and followed it closely on a leisurely sightseeing flight all the way to Cumberland. At its closest point, the river is 13 miles to the west of the prohibited airspace in flat, rolling farmland. Camp David is in the mountains. I could not have been the violating aircraft.

The controller was unimpressed. She had tracked a target on a straight line from P–40 direct to Cumberland. When the target disappeared from radar below the mountain ridges, she called the airport and asked who was in the traffic pattern. I was the only aircraft that landed within that immediate time frame.

Here’s where the habit of checking in with available radio services helped me out. Halfway along my flight to Cumberland, in VFR conditions, I had contacted the Elkins flight service station to get an updated weather briefing and give a pilot report. Nothing had required me to do that. The weather was fine; the clouds were few. But just to participate in the system, I had called.

I told my terse new acquaintance on the telephone that she should pull the radar tapes and Elkins radio logs from about a half-hour earlier. I told her the altitude, location, and time I had called flight service, and confidently informed her that she would find a radar target at that location and a radio recording that would match my identity. I suggested we could trace that target backward to its origin to confirm that I had not been the errant pilot.

She seemed puzzled, thanked me for the information, and said she would call me back.

This is clearly a case where my voluntary participation in the radio system afforded me confirmation of my identity and whereabouts surrounding a critical airspace issue. Many of my IFR friends tell me that’s one of the reasons they enjoy flying IFR even in good weather—they entirely avoid airspace problems simply by participating in the system.

There have been countless other examples where using VFR flight following services, purposely transitioning controlled airspace, or checking in with flight service has provided critical information to help me avoid a mistake. There have also been multiple times that controllers advised me of conflicting traffic that could have been deadly had I not seen it.

The point is this: While it is wonderfully enjoyable to fly free and quietly outside the air traffic control system, the controllers and briefers are there to help us. We should all develop comfort interacting with them and build consistent habits of utilizing the system.

A subsequent conversation with that Washington Center controller solved the mystery. An inattentive pilot flying direct from New Jersey to West Virginia had punched right through P–40. Apparently, at the same time I descended into Cumberland’s traffic pattern, the pilot was also overhead and descending below radar coverage to duck beneath a cloud layer just to the west. A case of bad timing led to the confusion.

It was my radio call to flight service that provided the concrete evidence the controller needed. I was cleared. And I was so glad I had called that briefer.