Aspects of Amelia Earhart that might surprise you

Celebrating Women's History Month with little-known facts about legendary pilot

One hundred years since taking her first flying lessons, Amelia Earhart remains in the news frequently, though often limited to a discussion of what happened to her, her navigator, and her airplane while on a circumnavigation attempt in 1937.

Focusing on her unsolved disappearance 84 years ago overlooks what propelled Earhart to celebrity status in her short lifetime: her sense of adventure, her determination, her confidence to break with the norms of the first three decades of the 1900s, and her commitment to promoting air travel and supporting women’s roles in aviation and the world.

1. She designed a roller coaster.

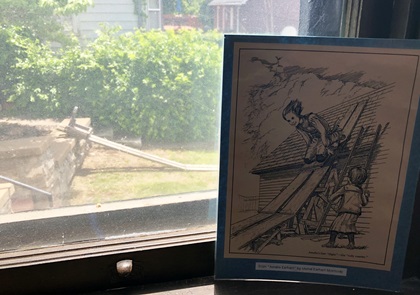

Propped up in a window at the Amelia Earhart Birthplace Museum in Atchison, Kansas, is an illustration of 7-year-old Earhart and her little sister Muriel enjoying a roller coaster the girls built with a packing crate to ride in and a ramp of wood planks propped against a shed roof. Right outside the window is a replica of the contraption based on the sketch, which appears in the 1977 children’s book Amelia Earhart written by Muriel Earhart Morrissey.

Earhart’s first ride ended in a crash, but she felt the exhilaration more than the bruises.

2. She called Atchison her hometown but moved a lot.

Earhart was born July 24, 1897, in her maternal grandparents’ house and lived much of her first 12 years in that home in Northeast Kansas. Her father’s work as a lawyer for a railroad, along with his alcoholism and financial troubles, led to quite a few moves during her childhood: Missouri, Iowa, Minnesota, and Illinois. Earhart attended six high schools in four years, graduating from Chicago’s Hyde Park High School in June 1915.

Among the places she lived as an adult were Pennsylvania, California, Massachusetts, New York, and Ontario.

3. She had plenty of nicknames.

Childhood nicknames—Meeley or Millie—followed her into adulthood, but Earhart most often referred to herself as A.E. in correspondence. The media dubbed her “Queen of the Air” or “Lady Lindy,” when in 1932 she became the second person after Charles Lindbergh to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean.

4. She learned to fly before she learned to drive a car.

Earhart took her first flight in December 1920 at a California airshow, just four months after women gained the right to vote with ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. She was 23 years old and said she knew immediately she wanted to learn to fly.

For lessons, she found Neta Snook at Kinner Field in the Los Angeles area. Just one year older than Earhart, Snook was the first woman to operate her own aviation business and was one of the first female graduates of the Curtiss School of Aviation in Newport News, Virginia. Snook gave Earhart her first lesson in a Curtiss JN–4 Canuck on January 3, 1921.

Because she didn’t drive, Earhart had to ride a bus and then walk four miles to the airfield. Snook taught Earhart to drive a car, too.

5. She loved fast, open, sporty cars.

Among the many jobs she took to help raise $1,000 for those early flying lessons was driving a gravel truck. For personal transportation, though, she loved the speedsters. She bought a 1923 Kissel Speedster Model 6-45 “Gold Bug” to drive herself and her mother when moving from Los Angeles to Boston in 1924. The bright yellow car attracted attention on the six-week cross-country adventure, as did the fact that two women were driving 7,000 miles alone.

A few other cars Earhart owned or endorsed were the air-cooled Franklin Airman line in the late 1920s and early 1930s, a 1932 Hudson Essex-Terraplane Special Sedan, and a 1936 Cord 810 Phaeton.

6. She was an influencer.

Earhart’s fame came after the 1928 transatlantic flight of the Fokker F.VII Friendship trimotor seaplane, when she became the first woman to fly as a passenger across the Atlantic. Brands wanted her to represent the face of adventure and of the modern American woman.

According to Barbara H. Schultz’s book Endorsed by Earhart, the enterprising pilot endorsed much more than cars: airlines, luggage and trunks, chocolate bars, collector cards, and Lucky Strike cigarettes, though she was a nonsmoker.

Earhart also wrote a book detailing her experience the same year as the Friendship flight, and her speaking tour for 20 Hours and 40 Minutes sometimes included three appearances in one day. She used the money to finance her solo flights.

7. She used her celebrity for good.

Earhart, who during her school days had kept a scrapbook of career women who inspired her, did her part to be a role model for others. She lobbied for women’s rights and took leadership positions to help effect change.

She helped organize the first transcontinental air race for women in 1929, and later that year a group of the women who competed formed an organization to support women in aviation, The Ninety-Nines, which still exists today.

She served as the first president of The Ninety-Nines in 1931, the same year she became the first female vice president of the National Aeronautic Association, where she helped establish separate female categories for records and races to reflect women’s lack of social and economic independence.

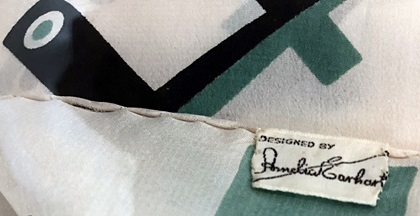

8. She was a fashion innovator.

Earhart often wore hats, dresses, and flight suits she designed and sewed. In 1933, she launched a clothing line featuring designs for active women. She sold pieces in department stores as well as patterns to make the clothes at home. She is credited with popularizing selling separates instead of suits limited to the same size top and bottom.

The Fashion Designers of America included her in their 1934 list of the 10 best-dressed women in the United States.

9. She insisted ‘The New York Times ’–and other media–use her professional name.

Aviation accomplishments were covered extensively by the media as the world continued to follow the development of flight. Earhart stood up for herself in 1932 when some media outlets, including The New York Times, referred to her as Mrs. Putnam after she married book publisher George Putnam in 1931.

After becoming the second person to fly solo and nonstop across the Atlantic, and the first woman, she sent a missive to Times publisher Arthur Hays Sulzberger to again remind him that she was Amelia Earhart, not Mrs. Putnam. The newspaper obliged.

10. She had a short but record-setting flying career.

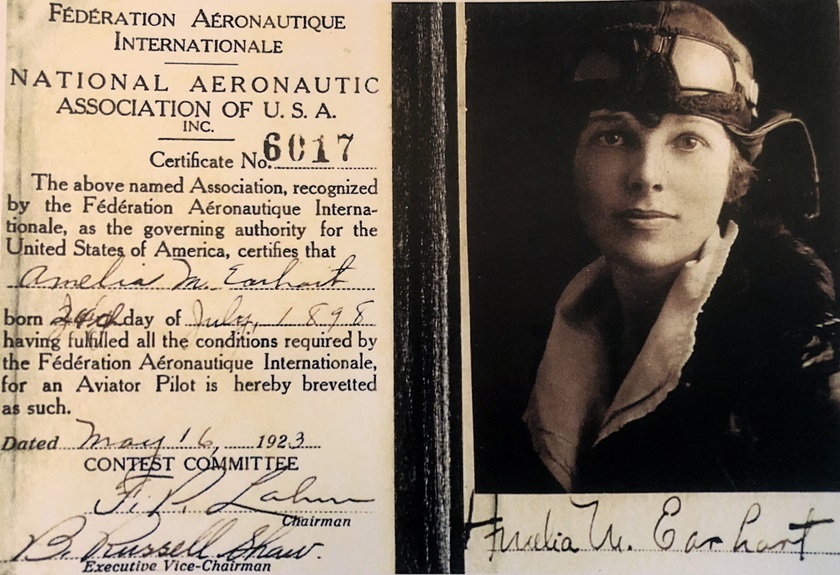

Earhart soloed in 1921 and in 1923 she became the sixteenth woman to earn an official pilot license (at that time from Fédération Aéronautique Internationale). She set her first unofficial record in 1922 as the first woman to reach 14,000 feet in altitude. She focused on school and work for several years and got back to flying again in 1927. The next year she began her string of “first” accomplishments and set seven women’s speed and distance records from 1930 to 1935. She achieved three important solo flight milestones for all aviators, male or female, during the first five months of 1935, including 2,408 miles from Honolulu, Hawaii, to Oakland, California.

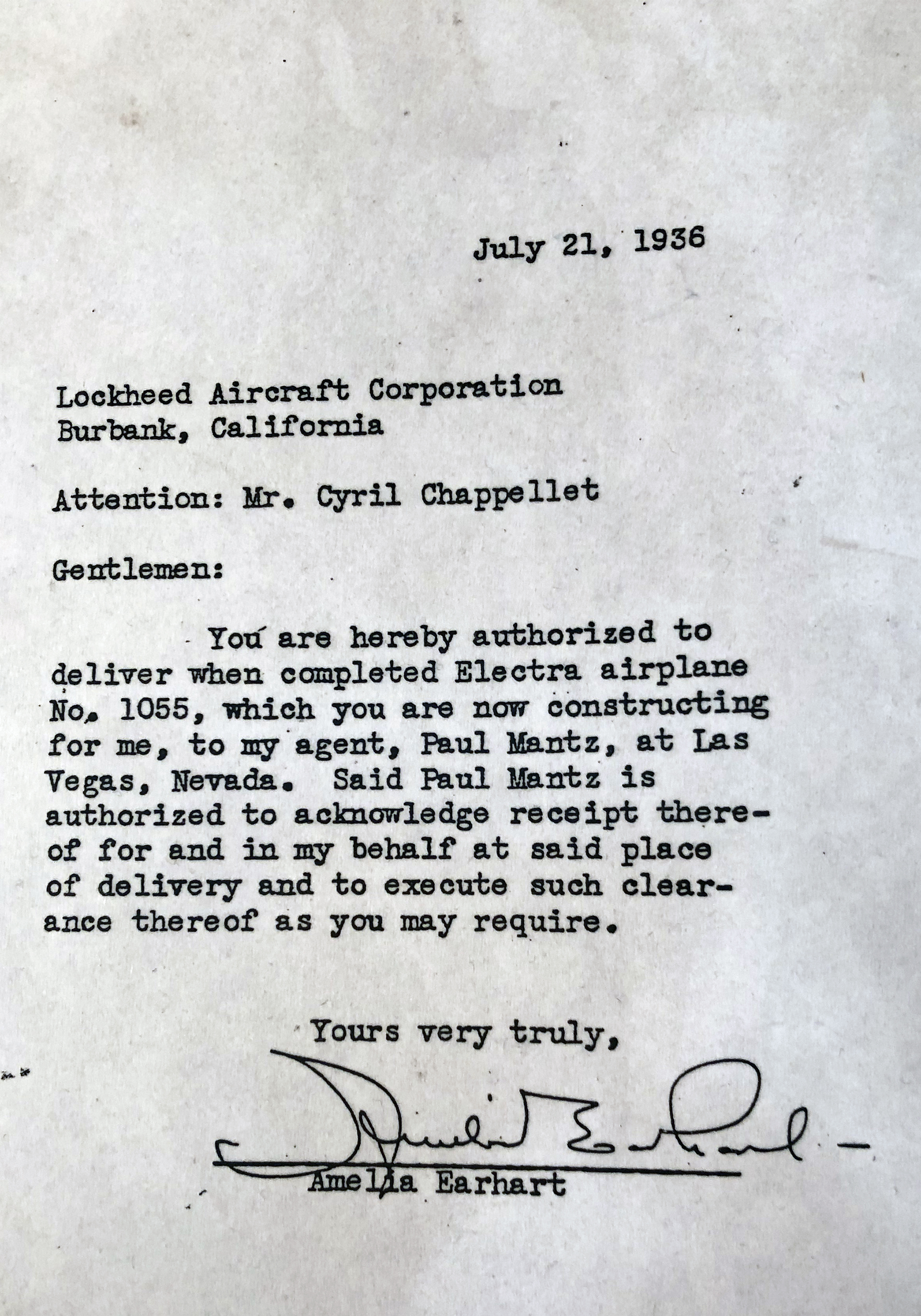

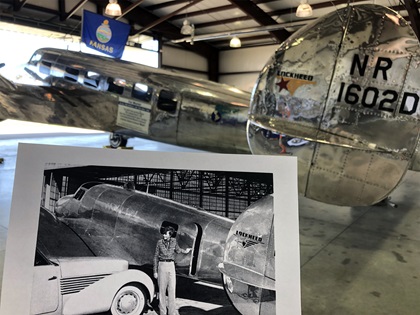

She was days shy of her fortieth birthday when the twin-engine Lockheed 10–E Electra was last heard from on July 2, 1937. Click here to read about the last known remaining Model 10–E, which has been modified to look similar to Earhart’s and is on display in Kansas.