Plume, fume, or doom?

Dangers of sudden smoke

By Laurel Johnson

It was a clear spring day. The weather was perfect, and my family was waiting for me to make the cross-country flight down the coast and through the mountain range from Seattle to central Oregon.

After two hours of easy VFR flying and gorgeous views, I was descending to land at Sunriver airport (S21). I had done a thorough weather briefing. No notams. No TFRs. No warning.

The approach to Runway 18 is circled by rising terrain and obstacles. In the channel of the terrain some light haze appeared. As I continued my descent, I realized the haze was light smoke. What I did not know and could not see until it was behind me on the 45 during short final, was a column of dark smoke from a controlled burn hidden behind the rock outcropping to my right. Controlled burns conducted by the U.S. Forest Department occur on calm wind days during the spring and fall season to mitigate the risk of summer wildfires. Winds here prevail from the west and can suddenly change or gust. Smoke movement is difficult to predict or forecast, given the variability of wind, terrain, and the density of the wood or grass fuel consumed. During my descent, wind or wind shear from the plume suddenly swept over me, churning swirls closing the aperture of my sight picture, obscuring the mountains around me and field below. It is slant range visibility that is most impacted by smoke, often driven by crosswinds.

As the saying goes “Where there’s smoke, there’s fire,” and, according to the FAR Appendix C, Part 121, 7-6-16, a plume of exhaust steam or smoke carries two other dangers: an invisible microclimate many times larger than the visible plume, and thermals or wind shear from the dynamic energy of rising heat.

What’s burning? A forest fire? A major fuel or tank explosion? Some sort of arson? Is my family on the ground OK? We train for emergency procedures when the airplane is on fire, but what if the airport is on fire? It never occurred to me that even a relatively small and concentrated fire in windy, mountainous terrain would create so much smoke.

I had three sudden thoughts: First, “I can’t see.” Given the mountainous altitude and unknown density altitude of the smoke, “I can’t climb.” And, if this keeps up, “I can’t breathe,” and neither can my engine. The thought of the potential of the engine choking on hot air, potentially dense particulates and microscopic embers searing hoses, the potential of clogging the air filter or affecting the static/pitot instruments made my heart sink.

Accidents from flying VFR into IMC have a fatality rate of 86 percent in noncommercial fixed-wing aircraft. According to the AOPA Air Safety Institute, one-third of these accidents involved instrument-rated pilots. I needed a shortcut, fast.

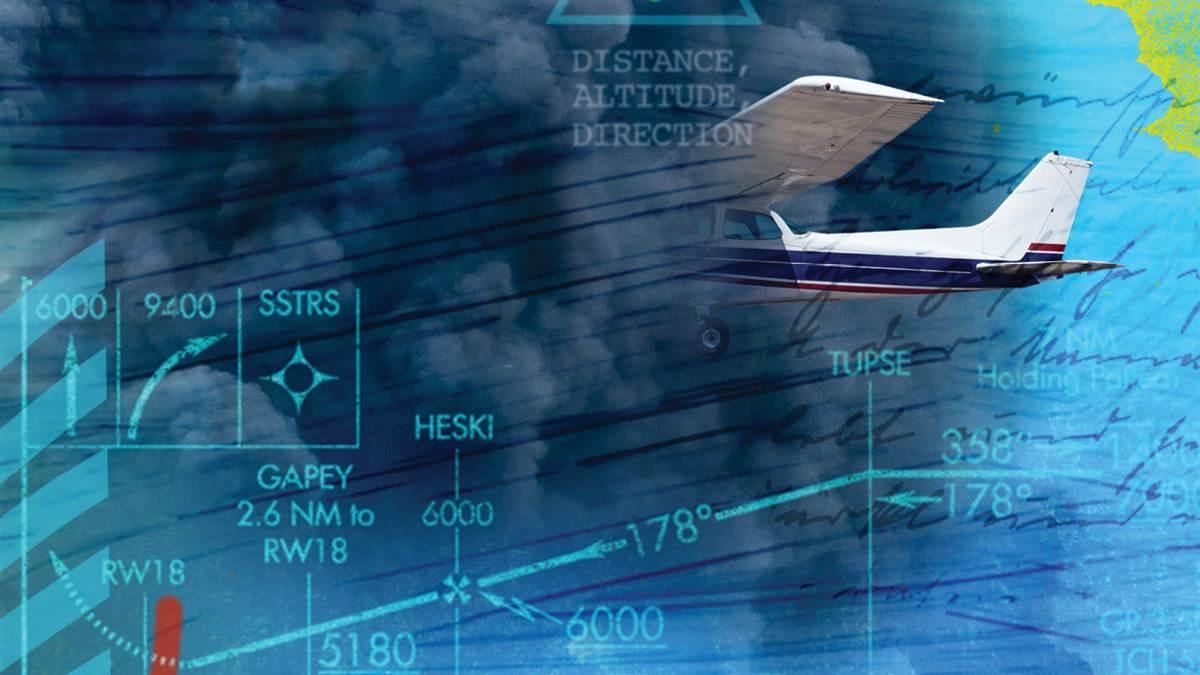

The human brain, even under stress, can remember three things. An acronym came back to me from flight training, from my father who inspired and taught me to fly. No matter what, I’ve always got my “DAD”—distance, attitude, direction.

I was not equipped with the GPS required for the RNAV approach, but I can read a plate. I pulled the plate for the instrument approach on the inbound runway and superimposed the image on the open VFR chart on my iPad. The minimum sector altitude was 11,600 feet msl, and the area was littered with unforgiving lava rock obstacles. A larger, invisible plume of heat and turbulence extends beyond the visible plume; I did not want to get blown into terrain to my left or disoriented making an uncoordinated turn in a microclimate of hot and turbulent air trying to make a 180. The altitude of the final approach fix waypoint was 6,000 feet. The instructions for executing a missed approach if I could not land were to climb to 6,000 feet: “That’s my out.”

I continued to fly the airplane at 6,000 feet over the approach course. My best field was in front of me and more than 5,000 feet long. On runway heading at 6,000 feet altitude obstruction clearance was assured, I would have better communication and visibility for ATC, respect the 2,000 feet above terrain when off victor airways mountainous areas guide, maintain line of sight to the VOR navaid behind me, and likely get better GPS signals to the iPad as backup to my steam gauge instrument panel. The altitude cushion would give me more distance to glide if I needed and built in the first step of the missed approach. All I had to do was fly runway heading and not get rattled.

The clock was my enemy, but it was also my friend. In fact, a clock with a secondhand sweep is required equipment for instrument condition flying. So how could I use it?

Visibility ahead was marginal, but my peripheral vision was swirling and disorienting. Glancing at the plate and ground speed I realized I had 3 minutes to the field. If I could see the field I would chop and drop, spiraling down to determine if it was safe to land. Spiraling over the airport would keep me far away from surrounding terrain and give me time to assess. If I couldn’t see the field I would proceed to the missed approach procedure, a climbing turn to the right from 6,000 feet. Then I would follow the IFR procedure to contact ATC for a pop-up IFR clearance or obtain flight following and plan to backtrack to my first alternate airport. Three minutes. Scan attitude, heading, altitude, clock. Decide and commit. Fly the airplane.

The blaze was brief, but intense. By the time I landed, shut down, and secured the airplane most of the smoke had cleared. What did I do right? Recognizing and prioritizing the visible and invisible risks of smoke and coming up with a quick action plan using IFR and VFR tools. What could I have done better? Follow up to alert ATC and other pilots by filing a pirep. I did advise the FBO and suggested posting a notam when there is a controlled or uncontrolled burn nearby in the future. Another point a local veteran pilot made was to avoid spiraling near limited visibility. His suggestion was to proceed south not to the nearest airport, Crescent Lake, but Christmas Valley to the southeast. In his 30 years of experience that is the longest runway and safest approach for best VFR visibility.

The next time I saw smoky haze 10 miles out at sunset, I diverted to Bend in a 180 turn. Smoke is fast moving, unpredictable, and may not be reported in a standard weather briefing or visible to ATC. Even in marginal or VFR conditions, visibility to land may be impaired. As you remember your barbecues during wildfire season, think about smoke aloft and pre-plan your aerial escape routes. Never forget your DAD. There’s nothing better than coming home safe, to celebrate with family, together.

Laurel Johnson is an aircraft owner and instrument-rated private pilot.