Toxic oversight

A cracked muffler turns a training flight into a tragedy

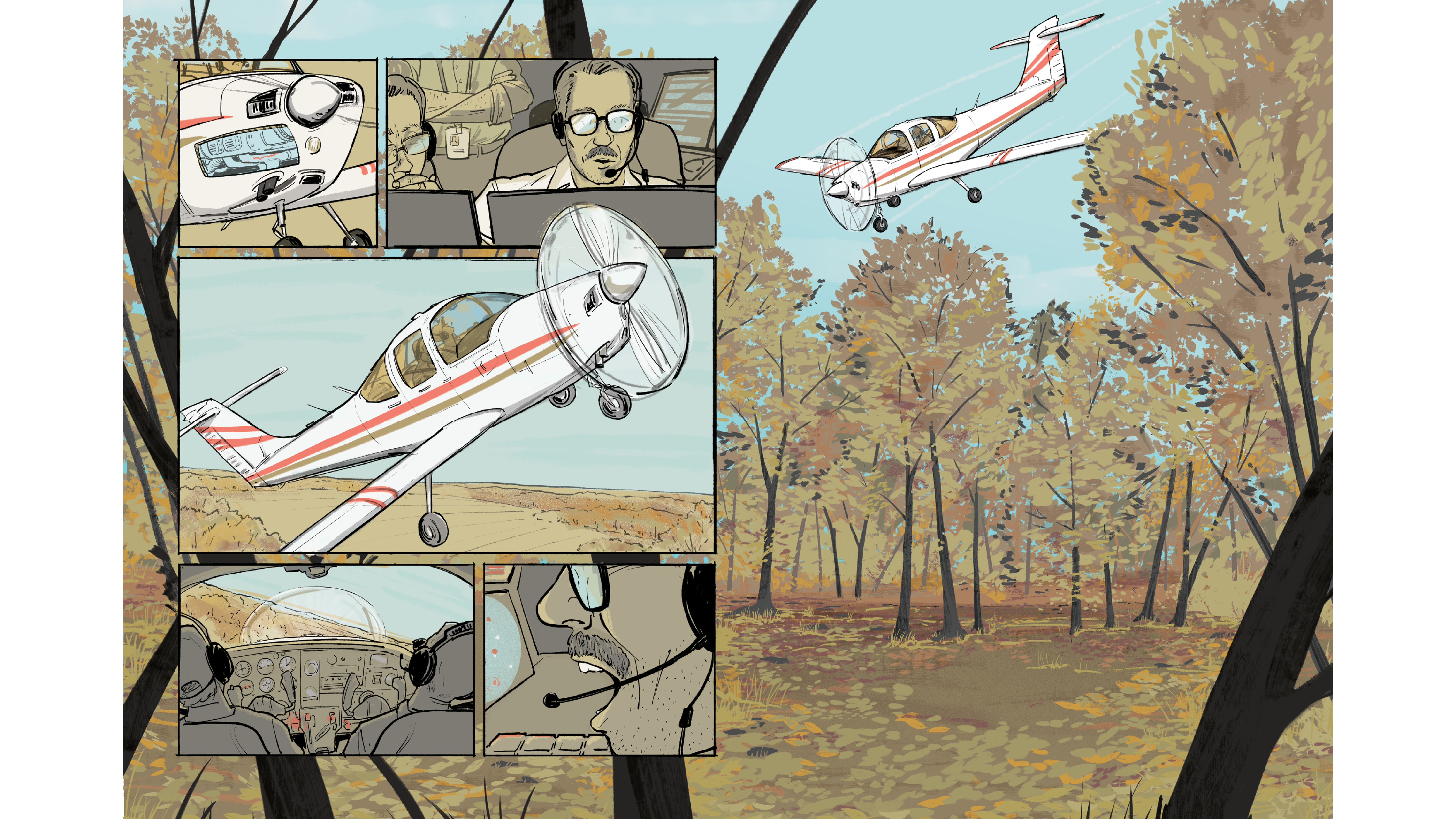

On November 30, 2020, a flight instructor and his student—a private pilot working on his instrument rating—spent the morning flying around north-central Arkansas. They departed Country Air Estates Airport (1AR9) just east of Little Rock, at 9:31 a.m. CST. The aircraft, a 1978 Piper PA–38 Tomahawk, registration number N9879T, had just come out of its 100-hour and annual inspections 10 days earlier.

The pilots’ first leg was to Carlisle Municipal Airport (4M3). After departing, they overflew Marion County Regional Airport (FLP), and continued on to Baxter County Airport (BPK) before turning eastbound. Their destination was Walnut Ridge Regional Airport (ARG). It was 11:46 a.m.

One of the pilots on board contacted Memphis Air Route Traffic Control Center (ARTCC) for an IFR clearance to Walnut Ridge, about 76 nm away. The controller told the pilot to squawk 4320 and change to a new frequency, which the pilot acknowledged and read back correctly. The Tomahawk was cleared to 3,000 feet.

All seemed well as the aircraft headed toward Walnut Ridge. But at 11:56 a.m., the controller noticed the aircraft drifting higher than its assigned altitude and asked the pilots if they would like a different altitude.

“November-Niner-Eight-Seven-Niner-Tango, I show you at three thousand six hundred, say requested altitude.”

One of the pilots responded: “[It’s] hard to hold, this airplane’s awful light, we’re trying to get back down to three thousand, Seven-Nine-Tango.”

“November-Seven-Niner-Tango, roger, would you like three thousand as your final or would you like higher?”

“Uh…three thousand as final is good, just having trouble holding it.” The pilot’s speech seemed slurred and his judgment clouded. But the controller accepted the response.

A minute later, N9879T requested an altitude change to 5,000 feet to “try to get out of this turbulence.” There had been earlier pilot reports of turbulence in the area, ranging from mild to severe. It appeared N9879T had hit a pocket of it. The request to climb is granted.

Two minutes later, the controller lost radar contact and attempted to reach the aircraft. There was no response. A second transmission also went unacknowledged. Shortly thereafter, the controller asked another aircraft to contact N9879T. It too received no response.

At 12:02 p.m., about four minutes after the last transmission from N9879T, the controller tried once again to contact the aircraft. This time, the pilot responded, but it was then clear something was wrong. The controller asked the pilot to switch to another frequency. While this transmission was acknowledged by the pilot, he did not make the change.

Two minutes later, the controller contacted the aircraft again.

“November-Seven-Niner-Tango, did you make the switch?” It was obvious that the pilot was confused.

“Seven-Nine-Tango…um…is there…. Nine-Eight-Tango…was it one-two-zero-point-three-seven?”

“November-Seven-Niner-Tango, it’s one-two-zero-point-zero-seven. Twenty-zero-seven.”

“Two-zero-point-three-seven,” the pilot responded, followed by some incoherent words. The controller was alarmed.

“November-Seven-Niner-Tango, is everything all right up there?”

There was no response.

At 12:05 p.m., the Memphis ARTCC controller asked the pilot for a radio check, to which the pilot responded, “We’re making the switch right now.” The controller then gave the pilot the altimeter reading at Walnut Ridge. It was not acknowledged.

At this point, the controller appeared to understand the pilot was in distress. He asked the pilot to respond to his message with two key clicks. The ATC recording shows an open microphone on the frequency for 10 seconds and some unintelligible voice transmissions. The controller then asked the pilot if he had oxygen on board. The response was multiple key clicks.

The controller tried again.

“November-Seven-Niner-Tango, if you hear this give me two key clicks.”

Two key clicks were heard on the frequency.

Even before the aircraft disappeared from his radar, the air traffic controller at Memphis suspected something was wrong and that the aircraft's occupants might be suffering from hypoxia.

At 12:07 p.m., the controller told the aircraft, “November-Seven-Niner-Tango, thank you. I acknowledge your two key clicks there. If you’re having issues and are needing emergency handling, give me three key clicks, three.” Three key clicks were heard on the frequency.

The aircraft’s flight track then became erratic. In the following minutes, N9879T’s ADS-B path showed inconsistent and unexplained circles with turns to the left and right. The controller gave the pilot vectors to the nearest airports in the vicinity of his last known radar position. His first suggestion was Sharp County Airport (CVK), about 25 miles to the northeast. He once again asked the pilot to respond with key clicks. The transmissions were apparently received and understood. The pilot responded with the appropriate number of key clicks.

The controller began to relay directions to the RNAV approach to Runway 22. He directed the aircraft to the procedure’s initial approach fix, KOCEG. He asked for key clicks in acknowledgement. His instructions were apparently understood by the pilot.

“November-Seven-Niner-Tango, roger, cleared direct Kilo-Oscar-Charlie-Echo-Golf, that is K-O-C-E-G, and advise you receive this with one key click.” One key click was heard on the frequency.

“November-Seven-Niner-Tango, from your last known position, it’s going to be approximately a zero-five-zero heading for Kilo-Oscar-Charlie-Echo-Golf and just give me one key click if you have that plugged into your computer.”

There was no response. It was 12:11 p.m. The controller then asked all aircraft on frequency to stand by.

In the following minutes, several transmissions from air traffic control as well as other aircraft were unanswered. The controller asked other aircraft to keep an eye out, and for the next hour, attempted to raise the aircraft on various frequencies, including emergency frequency 121.5 MHz. He also asked at least one aircraft to divert to the area where he lost contact with N9879T.

Almost two hours later, Memphis ARTCC controllers were still asking other pilots on frequency if they could help locate the Piper, hoping it had landed safely somewhere. But to no avail. N9879T had crashed into the woods just north of Franklin, Arkansas, at 12:13 p.m. The aircraft was destroyed and there were no survivors.

Analysis

Shortly after receiving the IFR clearance from Baxter County Airport to Walnut Ridge, the aircraft veered off the straight-line course, to the north. Later, it turned to the south and deviated again, by as much as 4.5 nautical miles.

Visibility was good that morning, with the lowest cloud ceiling at 5,000 feet agl, which was above the altitude N9879T had been cleared to fly. However, other pilots in the area had reported turbulence.

Even before the aircraft disappeared from his radar, the air traffic controller in Memphis suspected something was wrong and that the aircraft’s occupants might be suffering from hypoxia—therefore the question about oxygen on board. The pilot’s speech was slurred, and seemed to have difficulty responding to radio calls and following instructions, such as switching to a different frequency. The reason for this was clear following the toxicology report.

The National Transportation Safety Board’s final report, released in October 2022, stated that one of the mufflers had “multiple branched cracks,” which were apparently not examined closely (or at all) during the annual and 100-hour inspection, completed just 10 days prior.

While the aircraft’s maintenance logs showed that both the airframe and engine had undergone appropriate inspections, it appears the inspection was not completed in accordance with the Piper PA–38-112, Tomahawk Maintenance Manual. That document lays out in detail the requirements for inspection of the entire exhaust system. It begins with a warning in all capital letters: “A very thorough inspection of the entire exhaust system, including exhaust shroud assembly, muffler and muffler baffles, stacks and all exhaust connections and welds must be accomplished at each 100-hour inspection.”

It also says that the older the aircraft, the more “carefully” the system should be inspected. The accident Tomahawk was 42 years old, and as of the final inspection on November 20, the airframe had 7,084 hours. It had already flown 27 hours in the 10 days following the inspection. As the cracks were apparent to the NTSB investigator, how they were missed during the inspection remains a mystery.

The maintenance logs showed that the inspections were conducted by the flight instructor and aircraft owner, who also held an airframe and powerplant mechanic certificate, himself. On the same day, the log shows a separate endorsement for the annual inspection, approved by a different mechanic holding an inspection authorization, returning the aircraft to service in an air-worthy state.

Considering the time of year—late November—it was likely that the aircraft’s occupants had turned on cabin heat, which operated by using a heat shroud over the mufflers to draw the warmth into the cabin.

“The compromised muffler allowed combustion gases from the engine to enter the cabin heating system,” the final report stated. The NTSB concluded that the pilots were impaired by carbon monoxide due to the degraded muffler.

A toxicology report of the flight instructor’s blood detected carboxyhemoglobin of 29 percent—a clear indication of carbon monoxide impairment. According to the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), carbon monoxide in the bloodstream exceeding 20 percent “suggests significant poisoning.” The pilot receiving instruction had a carboxyhemoglobin level below the reporting limit of 10 percent. One explanation could be that the instructor’s carbon monoxide levels could have been building up for quite some time.

“Individuals exposed to carbon monoxide are often significantly symptomatic or unconscious before poisoning is recognized. The signs and symptoms are non-specific and may delay diagnosis. Patients commonly report headache, weakness, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, chest pain, or neurologic symptoms,” according to NIH.

Exhaust system leaks are the most common cause of carbon monoxide poisoning in general aviation aircraft. In its safety recommendation published in December 2021, the NTSB said that maintenance technicians “likely missed exhaust system failures during inspections, and that mufflers have failed in substantially fewer than 1,000 service hours.” So that should have been a warning to any technician servicing an engine with almost seven times that number.

Lessons learned

Like pilots, maintenance personnel are also human. And even the most experienced professionals can make mistakes or have an off day. The NTSB recommends “adhering to sound risk management practices” to prevent avoidable and common errors. It also recommends that a second qualified person, “inspect the safety and security of critical items.”

A year after this accident, the NTSB made a recommendation to the FAA, suggesting the regulator require installation of carbon monoxide detectors “with active aural or visual alerting” in all enclosed-cabin aircraft with reciprocating engines. The carbon monoxide detectors most commonly used in small aircraft are inexpensive printed cards treated with a chemical that changes color when carbon monoxide is detected. These color changes could easily be overlooked, for example during a night flight, or if the pilot is already stressed, overworked, or impaired. The cards also need to be replaced regularly, and their useful lives may be cut short if exposed to direct sunlight. The NTSB says there is often no way to tell if and when they have stopped working.

If you suspect carbon monoxide poisoning, let ATC know immediately, descend to a lower altitude, shut off the cabin heat, and increase fresh air ventilation as much as possible. If supplemental oxygen is available, use it. Once on the ground, seek medical treatment.

Carbon monoxide can build up over time and takes days to clear out of an oxygen-deprived body. In a worst-case scenario, it can lead to permanent brain and heart damage. And, of course, don’t fly again until the aircraft is inspected and repaired.

airsafetyinstitute.org/rps/hiddenhazard

airsafetyinstitute.org/rps/hiddenhazard