Go big

Homebuilt family hauler

Thanks to the engineering savvy of the airplane’s designer, Comp Air founder Ron Lueck (who is in the left seat), the airplane does not bounce; it simply shrugs off the firm landing and continues to track the centerline. “I like that, it was good,” says Lueck, happy to show me how rugged his airplane is. My landing sight picture, well-honed for the Beechcraft Bonanza A36 I flew to Titusville, clearly doesn’t work for this towering airplane.

Standing almost 12 feet tall at the tip of the tail, the carbon fiber composite Comp Air 6.2—introduced in 2022—is a large six-seat single-engine airplane. The factory demonstration aircraft we’re flying is powered by a 350-horsepower twin-turbo Lycoming IO-540 engine. However, since the Comp Air 6.2 is an experimental aircraft, a builder can choose from multiple powerplants, ranging from a 300-horsepower piston engine to a 750-horsepower turbine engine (see “Turbine Grin”).

“At Comp Air, we’ve been building airplanes since 1990,” Lueck said. “This is just the latest iteration of the same airplanes. We build bigger, family-oriented airplanes. That’s really what we specialize in: a human-sized airplane where you can actually fit six humans in the airplane and baggage.”

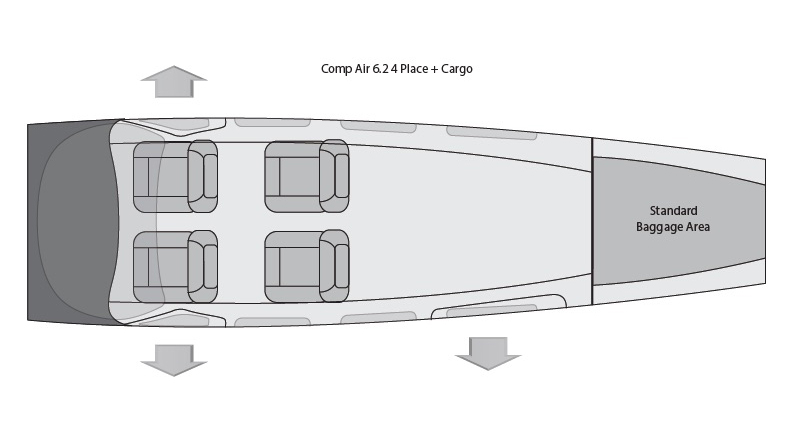

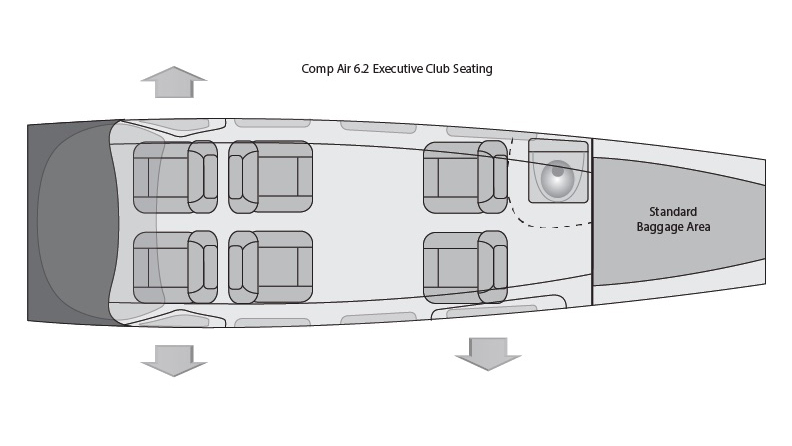

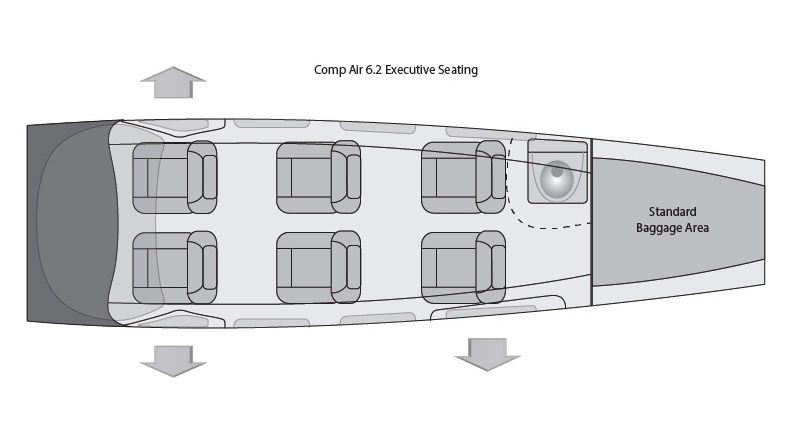

The math backs up Lueck’s claim. The aircraft’s 1,900-pound useful load enables it to carry 100 gallons of fuel, six 200-pound passengers, and some luggage. Its interior is spacious enough to enable passengers to move around the cabin in flight. “We have an option for a head in the back of the airplane as well,” said Lueck. “When you have kids, after an hour or so, that all of a sudden becomes an issue.”

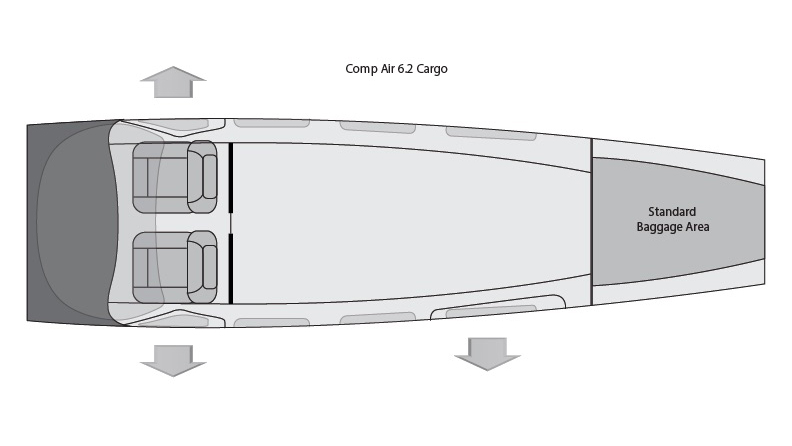

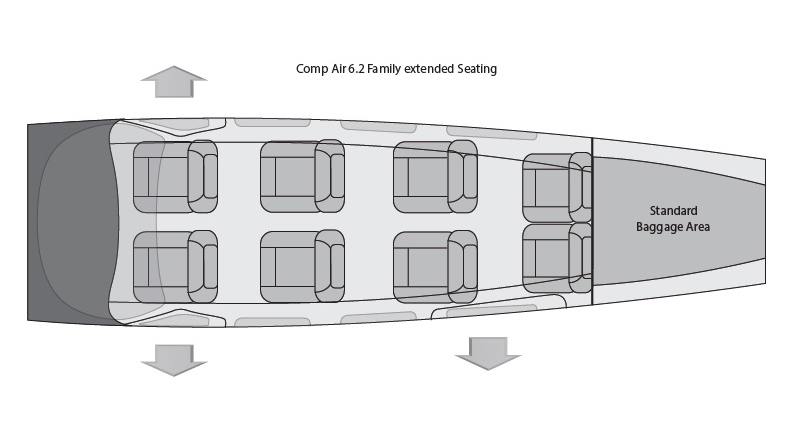

While the Comp Air 6.2 is nominally a six-seat aircraft, buyers can configure the interior multiple ways, ranging from “executive” with a curtained toilet to “family” with two additional small seats at the rear of the cabin. All seats can be removed to create a cargo configuration.

“When a customer buys the airplane kit, they have a choice,” said Lueck. “They can take it home as is, or we can assist them in doing stuff.” Most customers take advantage of Comp Air’s quick-build option; Comp Air assembles the two halves of the fuselage, which incorporates the vertical stabilizer, and puts the ribs and spars in the wings. “And then they can come along and finish the wing out. It gives everybody a level of comfort that we’ve done a lot. We know it. We designed it. We built it. So, the customer, and his family, are more comfortable knowing that they’re getting assistance in some of the critical stuff and there won’t be any problems at the end of the build of the airplane.” Comp Air also offers builder assistance to help the builder finish the fuselage, wings, tail, and control systems.

Lueck’s goal was to create an airplane with the utility of a Cessna 206 and the control harmony of a Beechcraft Bonanza. “My actual design, if I could make it fly like a Bonanza, that to me is the perfect airplane in flight quality. It’s just wonderful. We’re not quite there, but that’s where I shoot for,” he says as we prepare to fly the piston airplane.

Walking around the airplane during preflight, it is evident that Lueck and team have put significant effort into reducing drag. The Comp Air 6.2’s tightly cowled engine, lack of wing struts, and carefully faired junctions suggest a slippery design despite its fixed landing gear.

Passengers and bags enter through the cavernous rear clamshell doors, the bottom portion of which store fold-down stairs. Pilots can walk to the flight deck through the fuselage or climb through dedicated pilot and co-pilot doors with the aid of flip-down steps. After the steps are folded up and the doors are closed, the steps cleverly double as arm rests.

Once settled into the fully adjustable seat, I appreciate the clean layout of the all-digital instrument panel. The demonstration aircraft is fitted with a standard Garmin IFR avionics package, which includes dual 10.6-inch G3X engine indicating system displays, a GTN 650Xi navigator, and a GFC 500 three-axis digital autopilot. Switches, fresh air vents, and circuit breakers are logically arrayed on a subpanel, and a throttle quadrant and fuel selector are housed in a console between the pilots.

The fit and finish of the interior is average, with minor panel gaps and several areas of exposed structure. But standard interiors on experimental aircraft are often the bare minimum since builders tend to customize their interiors during the build.

Almost immediately after starting the engine on this 80-degree humid day in Florida, Lueck introduces me to one of the Comp Air 6.2’s nicest features—its powerful air-conditioning system. No ultra-expensive aviation-certified system is required on this experimental aircraft. Instead, Lueck sourced an inexpensive 10,000 BTU air-conditioning system from Amazon; it’s the same electric system that is used in conversion vans—and it works surprisingly well.

While taxiing to the runway, I enjoy the commanding view from the flight deck but quickly notice the rudder pedals require a significant breakout force to move. Once the nosewheel begins to turn left or right, the steering is precise, but Lueck acknowledges his team is still making adjustments to reduce the effort required to turn the nosewheel.We perform a standard preflight runup and line up on Runway 9 with takeoff flaps set. Advancing power achieves moderate acceleration at our low takeoff weight. It takes just 12 seconds to reach our rotation speed of 70 knots, and we’re airborne after a 900-foot ground roll, climbing at 1,500 feet per minute at 90 knots. I ask about engine cooling with the tight-fitting cowl, and Lueck suggests we see how hot the engine gets if we maintain full power during our cruise climb to 4,500 feet. We raise the flaps and keep the propeller at its maximum 2,400 rpm setting, and the airplane accelerates to 130 knots as vertical speed decreases to 600 feet per minute.

On a warm day, cylinder head temperatures on many high-compression engines race toward redline during a full power climb, but the Comp Air 6.2 remained at 403 degrees Fahrenheit—well below Lycoming’s recommended limit of 475 degrees during climb. Lueck said it took three different engine cowl designs to achieve sufficient cooling. He started with the most streamlined design possible, and gradually traded speed for cooling effectiveness with larger air intakes and NACA-style air extractors.

Once we level off, visibility over the nose is terrific. The leading edge of the wing is set well back from the windshield and pilot side windows, and the strut-free cantilevered wings provide an unobstructed view below. We set manifold pressure to 36 inches and keep the propeller at 2,400 rpm for cruise, seeing 175 KTAS with a 21-gallon-per-hour fuel flow.

“What are you doing? Did I tell you to do that?” Lueck asks as he leans the mixture. He turns to me and says, “I talk to my airplanes, I’m sorry. They never listen.”

After a chuckle, I make turns with only the ailerons to gauge adverse yaw, which I feel just a little of. The airplane requires just a touch of leading rudder entering turns, although the rudder still requires a heavy push in flight. “It makes a good IFR platform,” says Lueck. Comp Air set a differential aileron ratio of 2-to-1 to reduce adverse yaw and increase roll rate; for every 2 degrees one aileron goes up, the other aileron goes down 1 degree. The ailerons and elevators are operated by a combination of cables and pushrods, while the rudder is operated only by cables.

Steep turns require a moderate pull on the yoke to maintain altitude. This is when I discover the right-seat pilot has no access to elevator trim. The Comp Air 6.2 has no manual trim, only electric trim—and on this airplane, it’s on the pilot’s yoke, making flying this heavy airplane from the right seat a little more challenging.

Descending back to the pattern, the Comp Air 6.2 shows how slippery it is when it doesn’t want to slow down. The airplane has electric flaps that can be stopped in any position between zero and 40 degrees, which we begin to deploy to add drag to slow the airplane down. This pitches the nose up, which requires me to ask Lueck to add nose-down trim to compensate. We do this dance all the way to touchdown, but, hey, it’s an experimental airplane, so builders can add trim to the right yoke if they desire (the turboprop-powered Comp Air 6.2T has trim on both yokes). We slow to 120 knots on downwind, 100 on base, and 90 on final.

Feeling a little sheepish about the “firm” landing, I ask Lueck if he designed the airplane to land on rough fields. “Grass, no problem,” he said. “Even unimproved fields we’re OK with. The only thing you have to do is take the wheel pants off, because obviously mud and stuff pack into the wheel pants. The way I look at it, anywhere you’ll take a Cessna 206, I’ll take this airplane.”

Lueck peppers me with questions about my experience flying the Comp Air 6.2 compared to Cessnas and Bonanzas to unveil opportunities for improvement. The culture of experimental aircraft building abounds with bold new ideas and endless refinement, and Lueck is keen to design airplanes that are both capable and safe.

“We really want to emphasize safety,” he said. “Particularly since we try to sell this airplane as a family plane. If you’re going to put your family in the airplane, I want you to be safe. I want to know when you leave that you’re fully checked out in this airplane and I’m OK with you flying the airplane and you’re going to be great in the airplane.”

compairaviation.com

compairaviation.com