Visual descent points as decision points

Determining when to leave the MDA

By Bruce Williams

An approach briefing includes two key locations along the last segment to the runway: the final approach fix (FAF) and the missed approach point (MAP). Many procedures, however, include an additional reference that you should note when flying a 2D (nonprecision) approach. (For information about 2D and 3D approaches (see “Let’s Be Precise,” April 2025 AOPA Pilot).

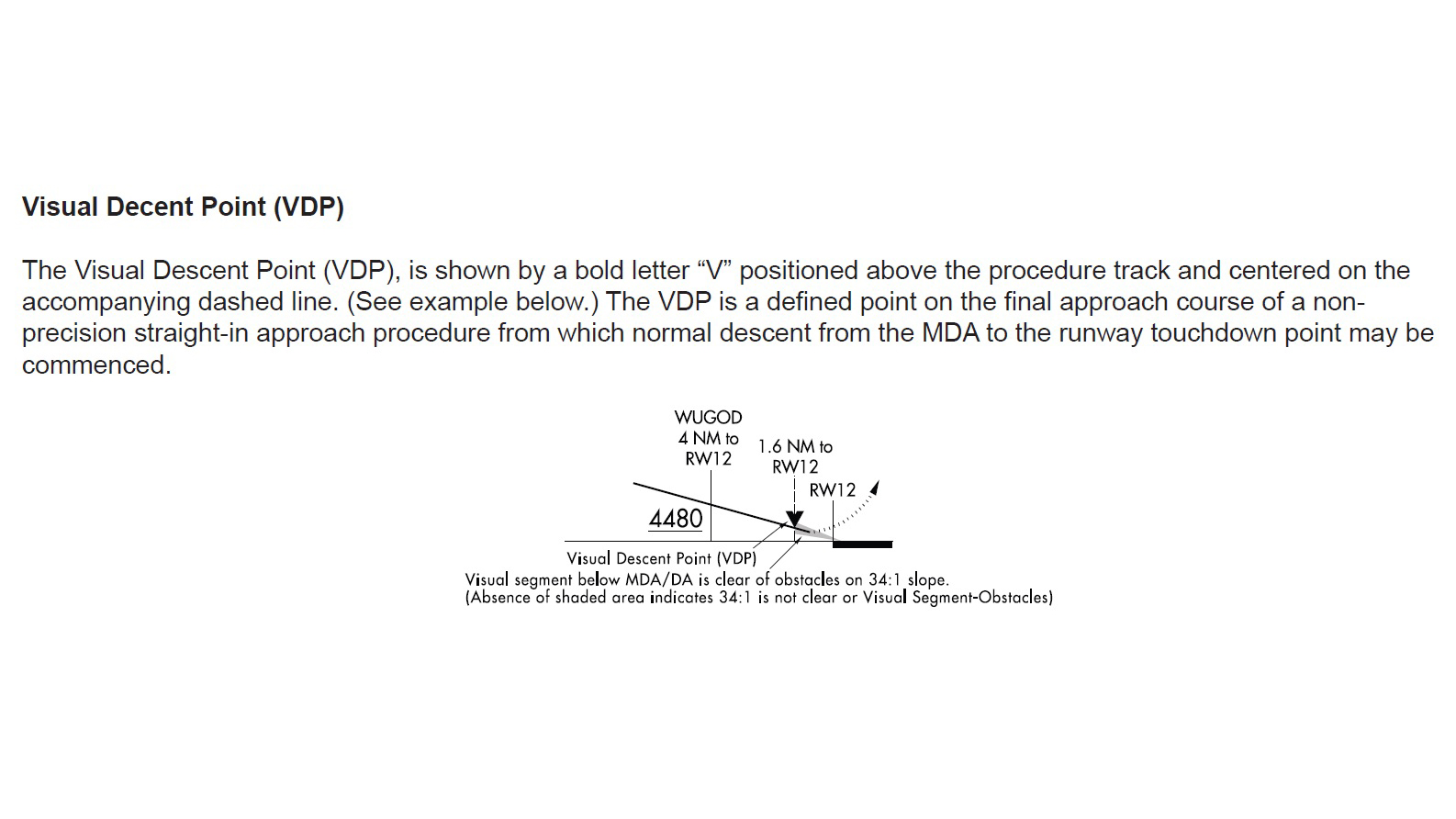

As the Pilot/Controller Glossary explains, a visual descent point (VDP) is “A defined point on the final approach course of a nonprecision straight-in approach procedure from which normal descent from the MDA to the runway touchdown point may be commenced, provided the approach threshold of that runway, or approach lights, or other markings identifiable with the approach end of that runway are clearly visible to the pilot.”

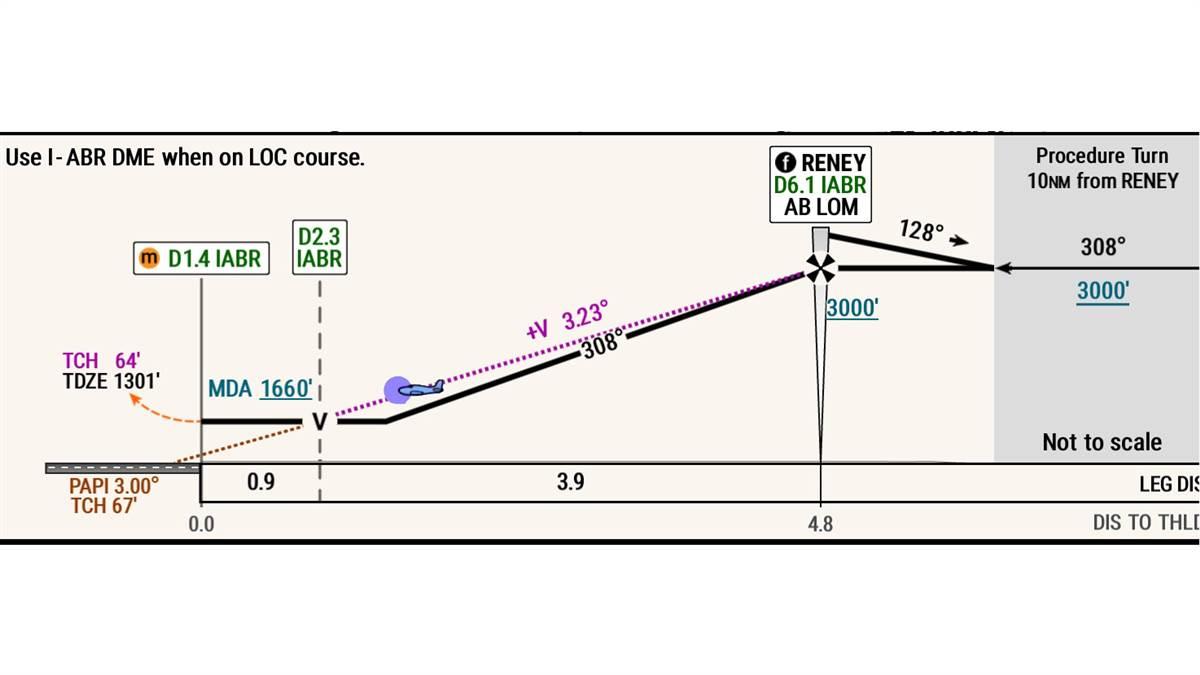

In other words, a VDP can help you begin a stable descent from the minimum descent altitude at an angle that typically matches the angle provided by a visual glide slope indicator such as a PAPI or VASI, or +V advisory guidance, if you have the runway environment in sight, per FAR 91.175.

Noting a VDP, however, is only the start of a process you should follow when planning and briefing a 2D approach. Key elements include confirming how you will identify reaching the VDP as you fly the approach, deciding if and how you will use the VDP, and reviewing the rate of descent and aircraft configuration needed to fly the published descent angle.

Understanding the basics of how designers create VDPs can help you answer those questions. Paragraph 2-6-5 in FAA Order 8260.3 (Terminal Instrument Procedures) explains that the FAA requires charting a VDP for straight-in approaches that have LNAV minimums, with some exceptions. For example, the primary altimeter setting must come from a source at the landing airport. The VDP also must be at least 1 nautical mile from other fixes in the final approach segment, and a VDP cannot be established prior to a stepdown fix. In addition, if obstacles intrude in the 20:1 visual area, or if the VDP would end up between the missed approach point and the runway, the chart can’t include a VDP.

Aeronautical Information Manual 5−4−5 provides operational details about VDPs. That paragraph first warns that “The pilot should not descend below the MDA prior to reaching the VDP,” and then notes additional considerations. For example, “The VDP will be identified by DME or RNAV along-track distance to the MAP.” But that paragraph doesn’t explain that VDP are not in navigation databases and don’t appear as waypoints in the list of fixes when you load an instrument approach. That important detail is buried back in AIM 1−1−17: GPS, which notes, “If a visual descent point (VDP) is published, it will not be included in the sequence of waypoints. Pilots are expected to use normal piloting techniques for beginning the visual descent, such as ATD [along-track distance].” In other words, you must note the distance (usually from the threshold) at which you’ll reach the VDP and include that detail in your approach plan. (If mental math isn’t your strong suit, the new profile view in Garmin SmartCharts or ForeFlight Mobile can help you track your progress as you approach a VDP.)

After you confirm how you will identify a VDP, you must decide what you’ll do when you reach it. Like many instructors, I advocate using the VDP as a decision point. Although a VDP isn’t a decision altitude, as noted earlier, it is the point at which, if the runway environment is in sight, you can continue a normal descent from the MDA to the touchdown point; otherwise begin the missed approach. If you continue past the VDP toward the threshold, by definition you must fly a steeper-than-optimum descent. (For a detailed description of DAs and MDAs, see “Decision Time,” September/October 2025 Flight Training).

Using a VDP as a decision point works most of the time, but the AIM alludes to circumstances that require further consideration: “When the visibility is close to minimums, the [PAPI or VASI] may not be visible at the VDP due to its location beyond the MAP.” For example, the required visibility for LNAV minimums on the RNAV (GPS) Runway 35 approach at Olympia, Washington (OLM) is 1 statute mile for Category A and B aircraft. But the VDP is 1.8 nm from the threshold. If the weather is at minimums, you probably wouldn’t see the runway environment at the VDP.

Legally, you can continue at the MDA for about another mile, hoping to glimpse the threshold. But as the AIM notes, “Aircraft speed, height above the runway, descent rate…and runway length…must be considered by the pilot to determine if a safe descent and landing can be accomplished.” Given the number of botched landings in the accident statistics, starting a descent beyond the VDP is a decision best made well before you begin an approach, with a clear understanding that what could work in a Cessna 172 might not be wise in an aircraft like a Beechcraft Bonanza, Cirrus, or Piper Malibu.

Bruce Williams is a CFI. Find him at youtube.com/@BruceAirFlying and bruceair.wordpress.com.