That ‘other’ front

Occlusions create widespread lousy weather

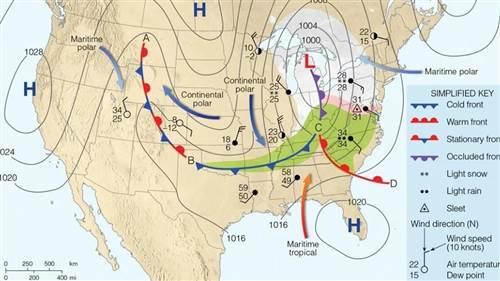

Cold fronts are shown as blue lines, with pointy symbols indicating the direction of the front’s movement. Warm fronts are red lines, with round red bumps on their leading edges, also showing their movement. Both fronts originate from a center of low pressure, shown by a large red “L.” And the counterclockwise winds generated by the low are what drives the entire system, called a frontal complex or cyclonic circulation.

The origins of what we can call the parent low usually come from troughs aloft at jet stream altitudes—say, 30,000 feet or so. As high-speed air moves around the trough’s apex it diverges. This creates upward movement of the air below, which in turn causes surface pressures to lower, leaving that big red “L.”

Sometimes frontal complexes aren’t simply that red “L” with cold and warm fronts rotating around them. Sometimes, cold fronts—which typically move faster than warm fronts—catch up with the warm fronts ahead of them. On the surface analysis chart, you can see the point where the cold front merges with the warm front; the parent low moves north, and where another type of front—an occluded front—begins to project northward. This is called the triple point.

The occluded front, or occlusion, is really two fronts because differing air masses merge at the surface, and lift the air between them, making another boundary aloft. That’s why occluded fronts are shown in purple, with leading-edge symbols alternating between those of cold and warm fronts. Some have likened this merging process to that of a zipper.

Even though occlusions are a sign of dying frontal complexes, they can generate a lot of adverse weather. There are three differing air masses being lifted, and plenty of moisture and turbulence in each. The stage is set for airmets, sigmets, and convective sigmets—and this entire system covers huge areas. But that’s not all. Once the occlusion’s “zipper” moves away from the triple point the system tends to slow down. For VFR pilots, low ceilings and visibilities could last for days. IFR pilots may find their destinations below minimums, with suitable alternate airports far away.

As if occlusions aren’t complex enough, there’s yet another detail: there are two types. Cold occlusions wedge under the air ahead them; warm occlusions involve cooler air riding up and overrunning colder air. Either way, waiting for the system to move east may be the best strategy.