Weather

Safety Spotlight: Mountain Flying

Weather in the mountains can change rapidly—always create a backup plan in case of unforecasted inclement weather. Be prepared to be flexible.

Automated weather reports are available at many airports, but they’re few and far between in the mountains. And while reports provide valuable information when available, they do not always give the full picture. Weather in the mountains can vary widely from airport to airport. At some remote strips, you won’t even have a windsock.

Off-Airport Weather Stations

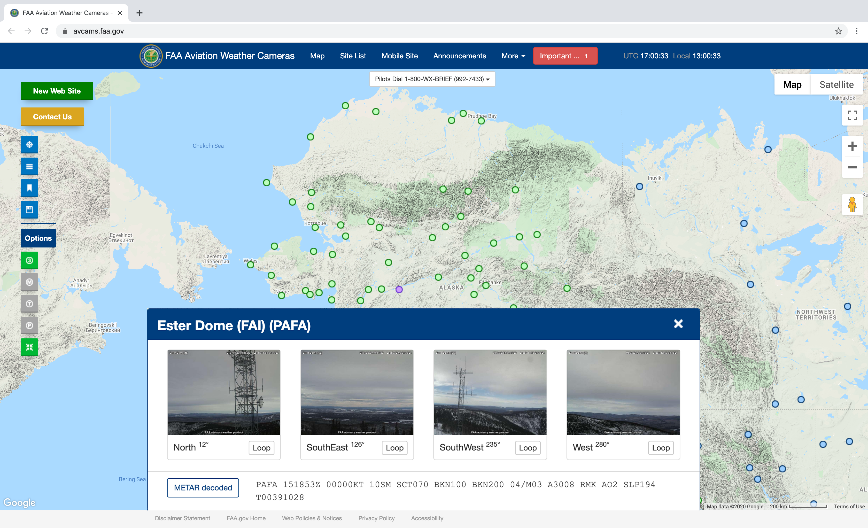

Pilots can use off-airport automated weather stations and weather cameras to fill in some of the gaps. Most are in Alaska, but pilots can also use mountain pass cameras in the Lower 48 for insight into weather, too.

Pilot Reports

Pilot reports, otherwise known as PIREPs, are the only source of information on actual in-flight weather conditions. They are especially useful between weather reporting stations. When flying in the mountains, consider your fellow pilots and file a PIREP for every flight!

Cloud Types

Cloud types often indicate what kind of air—smooth or turbulent—you’re likely to experience in flight.

Cap clouds: Cap clouds are formed by moist air that is pushed up the windward side of the mountain, where it cools and condenses, and down the leeward side where it warms and dissipates.

Rotor clouds: Also known as roll clouds, rotor clouds form on the leeward side of mountains by strong downdrafts and slower moving air near the surface. This creates severely unstable air, strong winds, and turbulence.

Lenticular clouds: These lens-shaped clouds are formed on the leeward side of mountains by rising air that condenses and cools at the crest of the mountain wave. The continuous lifting action of the waves is favorable for gliders.

Kelvin-Helmholtz clouds: These clouds are sometimes formed on the leeward side of mountains by two layers of air moving at different airspeeds, which indicate the presence of strong wind shear. They look like waves.

Icing

Mountain-related icing conditions are usually caused by moist air that becomes supercooled as it’s forced up the windward side of a ridge or carried upward in the waves on the leeward side.

Even more so than in the flatlands, icing in the mountains is serious business. Aircraft performance limitations often make it impossible to climb out of icing conditions, and descending can easily lead to controlled flight into terrain (CFIT). Avoid it altogether, and take swift action should you encounter unexpected ice.