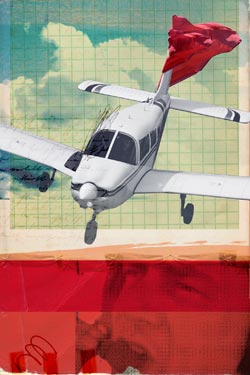

Never Again: Blowing in the Breeze

A Piper Archer pilot finds out that opening a door in-flight is no big deal... until you fly into a cloud...

I consider myself one of the lucky ones. I have a passion for general aviation and have found various ways to feed this passion ever since earning my private pilot certificate in 1979 and an instrument rating in 1984.

I consider myself one of the lucky ones. I have a passion for general aviation and have found various ways to feed this passion ever since earning my private pilot certificate in 1979 and an instrument rating in 1984.

I hit the jackpot in 1991 when I convinced my company to allow me to fly for business. I flew an average of 125 hours per year for five years in this capacity—all 100-percent funded by the company, and I loved every minute of it.

However, I found myself in a real jam during a business trip in late August 1992. I flew from my home base of South Jersey Regional (then 7MY, now VAY) to Louisville, Kentucky (SDF), home of our corporate office. I attended meetings and then headed to Columbus, Ohio (OSU), for a quick overnight visit to see my parents. I planned to return to New Jersey for a meeting the following day.

The night before leaving Columbus, I became concerned about weather for my trip. There was a widening area of low pressure on the East Coast and a warm front coming in from the Midwest—a perfect combination for significant convective activity. With the need to make the meeting and get the airplane back, I was getting concerned and a bit stressed. I decided to leave early the next morning to beat the weather. I was flying a rented Piper Archer, well equipped for the early 1990s with dual nav/com and glideslope as well as the much-desired loran.

From the weather briefing I knew I would encounter IMC, but no convective activity was forecast until later in the afternoon. All looked good, and I was excited to get some actual instrument time. I did the preflight, got my clearance, taxied to Runway 27, did a runup, and was ready to go. The tower cleared me for takeoff, and I was quickly rolling down the runway. Just before liftoff, I heard a huge gushing sound from the passenger side and realized that the door was not completely shut. It was too late to abort the takeoff, so I continued until at a safe altitude to assess the situation.

One of the things I quickly learned about a partially opened door and an airplane moving faster than 100 mph is there is no way that door is in danger of opening because of the strong outside pressure forcing it closed, but not latched. There was no real crisis, since the airplane was flying fine. I tried to close the door by pulling with every ounce of strength—but it was a no-go.

So now it was a question of options. The right thing would be to notify ATC of my situation and head back to the airport to get the problem fixed.

Never Again

Listen to this month's "Never Again" story: Blowing in the Breeze. Download the mp3 file or download the iTunes podcast.

Never Again Online

Hear this and other original " Never Again" stories as podcasts and download free audio files from our library.

Instead, I decided to forge ahead. My reasoning was straightforward: There was no real danger, just an annoying whooshing sound for a couple of hours; I was concerned about the weather and every minute counted—I just didn’t have 30 minutes to waste; and I didn’t want to ’fess up to ATC if I didn’t have to.

Everything went smoothly for about 45 minutes, until I entered IMC near Pittsburgh. Clouds are wet, which normally would be fine—unless you are flying with a partially open door. Suddenly I found myself dealing not just with airflow but water flow, and lots of it. The element of danger had escalated a bit—so what now?

I could still confess my predicament to ATC and land at the nearest airport, or I could try to stop the leak. There was an old sheet in the backseat, used as a makeshift cover to protect the panel from the sun while the airplane was tied down. I decided to wedge the sheet into the opening to keep the rain from pouring in, but the moment I did this I heard a “whoosh” sound and the sheet was gone.

As if I didn’t have enough to deal with, another issue popped up. I noticed the CDI on the number-one VOR was shaking erratically back and forth, as though it had a loose connection. I tuned in the number-two VOR and got the same results. I checked for audio verification and heard a choppy version of what seemed to be the correct Morse code.

There was something wrong with the VORs, and now I had to inquire with Cleveland Center. The controller was very helpful and contacted another aircraft on the same frequency and airway to see if it was experiencing VOR reception problems. Of course, the answer was no. They were flying all fine and dandy through the soup, while I was sweating at about the same rate the rain was pouring through the dreaded open door.

My only choice now was to finally admit my predicament to ATC and get assistance.

The closest airport was in Clarksburg, West Virginia (CKB), with marginal VFR conditions. I was immediately turned over to Clarksburg Approach to set up for an airport surveillance radar approach, where I was handed off to the “final controller,” who gave me progressive course and altitude changes until I was lined up with the runway and had the airport in sight.

I was handed off to the tower and cleared to land. Then came the final embarrassing moment. About one mile on final, the tower said, “Cherokee Eight-Seven-Seven-One-Charlie, it looks like you have something hanging on your tail, did you lose something?” I wanted to crawl into the crack of the door and hide from the world. But I had an airplane to land, a mission to complete—and a sheet to deal with.

While taxing to the ramp I heard some chuckling in the background while ground control issued my taxi clearance.

Further examination confirmed the sheet had attached itself to the tail after performing its disappearing act from the cockpit. Of course, the VOR antennas are at the top of the tail, so no surprise why my reception was choppy at best.

I did get a little sympathy from the FBO manager, who had witnessed the whole thing. He assigned a mechanic to tighten the antenna. All was good on the way back to New Jersey, and the dreaded thunderstorms never appeared.

Lesson learned: Don’t let a series of events become your accident chain. Confess early and you’ll have many options. In my case, I was probably one chain link away from disaster.

Randall Taussig, AOPA 654764, is an instrument-rated private pilot with more than 1,500 hours. He resides in Reston, Virginia. Illustration by Sarah Hanson.