Anthony Marsh shows the route he took out of his stricken Piper Cherokee 180 as it sank in Old Tampa Bay. Photo courtesy Anthony Marsh.

Anthony Marsh shows the route he took out of his stricken Piper Cherokee 180 as it sank in Old Tampa Bay. Photo courtesy Anthony Marsh.

The highway bridges below were tempting, nearly irresistible in the predawn silence as Anthony Marsh guided his stricken Piper Cherokee 180 over Old Tampa Bay, the propeller windmilling uselessly ahead of him, and St. Petersburg-Clearwater International Airport suddenly out of reach.

Marsh, 47, was finishing a cross-country from Pennsylvania, anticipating a happy reunion with his girlfriend in Clearwater, Fla. He had departed Doylestown Airport in Doylestown, Pa., hours before with a fuel stop about halfway along the route. He said he should have had about eight gallons left in the tank, and the 1967 Piper was in “tip top shape,” though the original engine was nearly at its 2,000-hour limit. He was lined up on a long final to Runway 22, and had just crossed over the Courtney Campbell Causeway at about 1,000 feet when the engine quit.

“That’s one thing I will never do again,” Marsh said of his decision to descend to pattern altitude so far from the field. “There’s no reason to get down to pattern altitude so early and drag it in.”

Marsh was in contact with the tower and declared an emergency, running the emergency checklist and scanning the blackness below for options. There was the causeway he had just crossed, and the Bayside Bridge to the west, which nearly parallels Runway 18.

Carb heat on, electric fuel pump on, mixture full rich, no joy. He switched the fuel selector from the tank he was running on to a tank he had run nearly dry, based on his calculations, and the engine sparked to life for just a second or two. He switched back to the tank that should have had eight gallons left, and the engine sputtered to life again, only for a second or two. The gauge showed roughly eight gallons remaining, but “those gauges are notoriously inaccurate. I never rely on them, anyway.”

A private pilot with instrument and multiengine ratings, more than 700 hours logged including more than 450 in the airplane he had owned for nine years, Marsh quickly realized all he could rely on was his training and judgment. Even at roughly 2 a.m., there was traffic on the highways and light stanchions forming a canopy over the causeway. The Bayside Bridge was perhaps a better bet, and within reach, but he could see tractor trailers passing below him at speed, and imagined “getting balled up” if he landed in front of one.

“I did definitely consider preservation of other lives and property,” Marsh said in a telephone interview Feb. 27. “I wanted that highway. I could have made that highway.”

It was a temptation he was able to resist, and a decision he gives himself some credit for: Down to 500 feet or so, he decided the water was his best option, and at least he would avoid endangering motorists. “They didn’t want this to happen to them.”

Anthony Marsh paid salvage divers $1,300 to retrieve his 1967 Cherokee 180 from Old Tampa Bay. Photo courtesy Anthony Marsh.

Anthony Marsh paid salvage divers $1,300 to retrieve his 1967 Cherokee 180 from Old Tampa Bay. Photo courtesy Anthony Marsh.

Marsh is not sure if he remembered to buckle up—he often loosened his seatbelts in flight—and the engine stopped as he was starting the pre-landing checklist. He is sure he neglected one step in the pre-ditch checklist: cracking the door open, an omission that nearly cost him his life. Aiming for the inky blackness where he knew the water must be, he also opted not to extend flaps, or turn on his landing light. He was struggling to come to grips with the reality of the moment. He did keep his radio on, in part because he needed to hear a human voice.

“You’re scared when you’re alone and you have no one to talk to,” Marsh said.

In retrospect, the landing light and flaps might have been helpful, Marsh said. He slowed to about 70 knots on the final descent.

“I saw the water at the last second and I flared,” Marsh said. The impact was tremendous. “It’s unreal. It was an instant crash, white spray like a car wash … I went to meet that white spray with my face.”

When he regained consciousness, “I realized I was upside-down in the water,” his airplane sinking nose-down in about 15 feet of water. Water rose past his neck, and he was unable to take a deep breath before the “water came over my eyes.”

He imagined he was about to drown, and thought of his mother, kids, girlfriend waiting in Clearwater, and fought to live. He began to kick and kick at the windshield, finally breaking a hole in the copilot’s side large enough to pass through. As he escaped, he felt the airplane settling on top of him, and braced himself against the muddy bottom and pushed. Somehow, he managed to break free, and find the surface, beckoned by the lights from the nearby bridge.

The aileron and tip of the left wing were still above water, and he took refuge there. It was about 45 minutes before the rescue boat arrived, long enough that even the roughly 60-degree water chilled him to the bone.

“I was hypothermic when they came to get me,” Marsh said. Though bruised and cut from the sharp edges of the Plexiglas, he was alive. Undeterred by the harrowing event, Marsh said he plans to fly again.

After spending four hours in a local hospital, he returned to the bridge to meet the salvage crew he had summoned to retrieve his wrecked Cherokee, and one final lesson: It does not pay to allow insurance to lapse.

Marsh said he had reasoned the old airframe was not worth enough to justify a $700 premium, but lost thousands of dollars in electronics and other belongings inside, and had to pay $1,300 to have the airplane—and the cash he had brought with him—hauled out of the water.

“I paid them in wet $100 bills,” Marsh said, noting he still had to write a check. “I wish I had that $700 insurance. You don’t have to have insurance, but you should.”

Marsh listed various lessons learned.

“You have to expect the unexpected,” Marsh said. At night, over unfamiliar terrain (water, in this case), he said he should never have descended so early. “Dropping down to pattern altitude two-and-a-half to three miles out was a huge mistake.”

Marsh is unsure why the engine died, but suspects a problem with the fuel pump. It is unclear to what extent the NTSB will investigate, he said.

He believes that not giving into the temptation of those bridges might have saved lives, including his own. The outcome could have been far worse: landing on concrete only to be run over by a truck.

“I lived,” he said. “I lived.”

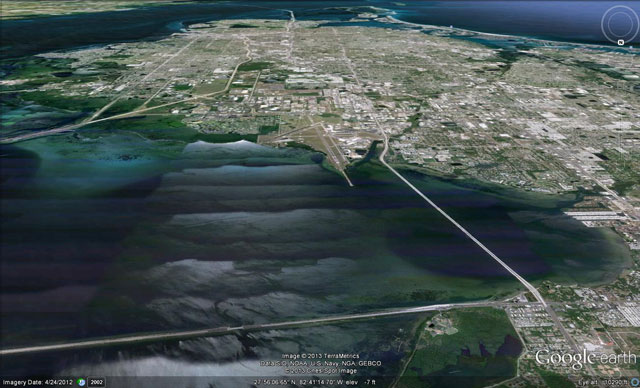

In this south-facing view from Google Earth, the Courtney Campbell Causeway runs east-west at the bottom of the image, and the Bayside Bridge runs north-south. St. Petersburg-Clearwater International Airport is also shown. Marsh ditched just west of the Bayside Bridge. Google Earth image.

In this south-facing view from Google Earth, the Courtney Campbell Causeway runs east-west at the bottom of the image, and the Bayside Bridge runs north-south. St. Petersburg-Clearwater International Airport is also shown. Marsh ditched just west of the Bayside Bridge. Google Earth image.