Aviation Access Project offered fractional ownership for piston aircraft, with the promise of professional management. But customers across the country—who bought shares in aircraft the company did not own, purchased franchises, or, in some cases, both—learned a painful lesson when the money they paid in disappeared, and promised resources, aircraft, and support never came.

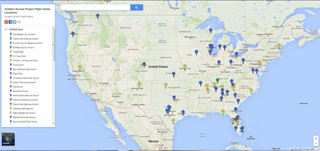

The company launched in 2012, seeking directors for franchise flight centers around the country to recruit customers and manage local aircraft operation, maintenance, scheduling, and marketing. In return, the company would provide business support, such as centralized bill payment and an online aircraft scheduling system. Through its website and social media posts, the company announced a steady stream of new flight centers opening across the country during 2013, but only one location actually operated for any length of time, and only two aircraft operated on company business.

In December, Aviation Access Project CEO Rick Matthews said company operations had been “suspended” pending fresh investment. “We couldn’t satisfy the demand… it’s a bittersweet decision, knowing that you hit on something.”

Those who invested and described their experiences to AOPA said they were met with broken promises. Franchise and aircraft share purchases, with individual investments ranging from $1,000 to $22,000, were not repaid.

Matthews said in a recent telephone interview that he personally invested more than $100,000 in the company. However, he did not explain in any detail where that money (or funds invested by others) was spent, beyond citing unspecified website costs and other business expenses such as insurance.

Matthews said he is working to raise capital from unnamed investors, and vowed to repay everyone. “I am taking full responsibility,” Matthews said. “This next round, I’m going to set aside probably $100,000 … to fix things, take care of people.”

Those interviewed said Matthews has reportedly made similar promises at various times, claiming that an angel investor was poised to provide a huge influx of capital.

“It is a mess, I admit it,” he conceded, saying he hopes to sell the company. “I’m so willing to remove myself from it.”

Dreams dashed

Roy Royster, one of 15 people listed as Aviation Access Project “Flight Center Directors in place as of July 2013,” said “that whole thing appeared to have been a scam.” Royster is among only six people known to have even attempted establishing a local flight center under Aviation Access Project and the only one to have a franchise that operated an aircraft for any length of time.

Royster opened his Auburn, Alabama, flight center in August 2013, and a Flight Design CTSW arrived soon after. But bills went unpaid, and on Feb. 14, 2014, the aircraft was repossessed, despite Matthews having personally paid $8,000 toward the aircraft, according to Matthews and Royster.

“We were left with nothing,” Royster said, explaining that he and two others in the Auburn area who bought in on the franchise lost the $50,400 they had paid for shares in the aircraft.

Matthews, in a recent telephone interview, accused Royster of failing to live up to his responsibilities in the deal. “Mr. Royster misrepresented himself under false pretenses,” Matthews said. “He performed virtually none of the services of a director.”

Royster provided copies of maintenance bills he said he paid personally, and said that for a time he had worked to recruit additional customers. Royster said a local flight instructor hired to teach the new shareholders wasn’t paid for weeks. “It turned out that Rick was not paying her on time,” Royster said. “That put a little suspicion in my mind.”

David Kiracofe signed a franchise agreement in June 2013. He alleges in a lawsuit that he paid $10,000 in two installments to facilitate securing an aircraft for a flight center he planned to establish in Florida. Support promised by the company in the franchise agreement did not materialize, prompting Kiracofe to demand a refund, and then file a lawsuit in May 2014. Kiracofe said that to date, his lawyer has been unable to ascertain where Matthews lives or works, and has been unable to serve Matthews with legal notice required for the lawsuit to proceed.

Tony Hebert was so enthusiastic about the potential he saw in the Aviation Access Project concept that he paid $17,000 and signed a franchise agreement in February 2013 to open a flight center in Augusta, Kansas.

“I had gone as far as setting up an LLC,” Hebert recalled. “The airport administrator was literally building me an office at the airport.”

Months went by before Matthews arrived in Augusta for a site visit, Hebert said. “Rick never, I mean, according to the agreement that I signed, Aviation Access was supposed to come out and help you do all this stuff. After he took money from me it was pretty much, I’m done with you. Off to the next. Off to the next pocket.”

Hebert said he incurred additional expense flying a Cessna Skycatcher from Kansas to Gallatin, Tennessee, on behalf of Aviation Access Project for an event.

“Rick made an attempt to reimburse me for the expenses that I incurred flying the Skycatcher out to Gallatin, and the check bounced,” Hebert said.

Hebert said that Bruce Haines, who served as the chief financial officer for Aviation Access Project, told him he had no idea why there were insufficient funds in the account.

“When it hits you and you realize this is a scam, you kind of just shut down and you carry on, which is pretty much what I did,” Hebert said. Hebert, like other flight center directors, said he never met Haines face-to-face.

Haines refused to answer any of AOPA’s questions about Aviation Access Project, referring all questions to Matthews.

Red flags

Royster said an email from Haines on Oct. 30, 2013, made him consider the possibility that he was being scammed.

Royster had asked Haines for access to financial documents, action on overdue payments, and fulfillment of promised online scheduling support in the weeks leading up to this email which Haines apparently sent to Royster in error:

“Rick, Well, I'm going to pass the buck on this one - see Roy's first request about the 54K. Personally I don't think we owe him any explanation, but this guy had a lawyer read his FC docs. Could be a sticky one, suggest you give some thought to what to tell him. Suggest further consultation with Anthony or an attorney before you say anything to Roy. I think this guy is trouble...... Bruce.”

Matthews responded by email to Royster the following day, apologizing for Haines’ email and urging Royster to communicate with him (Matthews) directly.

When asked about that email from Haines to Royster, Matthews agreed it did not sound like the communication one expects from a legitimate business.

“Right. It would surely sound that way,” Matthews said. “I wasn’t real happy with Bruce’s words. We were just trying to figure out what to do.”

Royster said this particular email solidified his opinion that he was the victim of a scam.

Leonard Assante, Aviation Access Project’s unpaid vice president of communications, said he never met Haines in person, and had little contact with the company financial chief.

“I knew about bills not being paid. I remember badgering Rick,” Assante said. “…most of the guys would talk to me when they couldn’t get a hold of Rick. I got a lot of, ‘Rick’s not answering his phone.’ He (Rick) was always like, ‘Everything’s under control, everything’s fine. Don’t worry about it.’ Obviously, that wasn’t the case. I learned my own lesson later on when I got sued.”

Assante said he personally lost more than $10,000 through his involvement with Aviation Access Project, including $5,000 paid to settle with Kiracofe. Assante, who was as much the public face of Aviation Access Project as Matthews for nearly two years, said he cut ties in large part because of the lawsuit and Matthews’ apparent lack of concern about the pending legal action.

Problems acquiring aircraft

Acquiring aircraft with little or no money down was a challenge for the company. Aviation Access Project operated one Flight Design CTSW in Alabama and a Cessna Skycatcher that appeared at multiple locations and company events.

The circumstances under which Aviation Access Project acquired the Skycatcher in 2013 remain unclear. Cessna Aircraft officials declined repeated requests to comment on the arrangement, and various people with knowledge of the transaction gave somewhat inconsistent accounts. “They agreed to lease one unit to us, Cessna did, in order to help us do a proof of concept,” Matthews said. (The Skycatcher appears to have been repossessed by Cessna in early 2014.)

Also in May 2013, the company announced an agreement with Flight Design, to “work together.” Flight Design USA President Thomas Peghiny said the agreement was “nothing more than that,” essentially a memorandum of understanding with no financial commitment by either party.

“They called back,” Peghiny said. “They wanted us to donate an airplane.”

‘I think it’s worthwhile’

Peghiny said Flight Design supports the concept of shared ownership and believes it could help transform general aviation. But what happened to nearly everyone who bought in was “the worst thing possible” for GA, Peghiny said.

Aviation Access Project’s concept garnered the GA community’s attention, including social media and aviation press. (AOPA mentioned the project in the August 2013 issue of AOPA Pilot.) Matthews had envisioned “redefining the industry” and establishing 1,000 flight centers across the country.

“We’re in this to literally transform the industry,” Matthews said in 2013.

Darden Hamilton, who has had an extensive career in aerospace, business, and public office, having served two terms as an Arizona state senator, said that he helped Matthews develop the concept in various conversations dating to 2011 or 2012.

“His business plan looked viable to me,” Hamilton said, adding that he only provided advice.

“I kind of feel for him. I thought he had a really good idea. I’m just sorry it turned out the way it did,” Hamilton said. “I hope somebody else can pick up that ball and run with it. I think it’s worthwhile.”

Brandon Dillon, an unpaid advisor and friend of Matthews, said he believes Matthews had honorable intentions that just went awry. Dillon said he had many long conversations with Matthews about how to save GA.

“I still believe, unless I really was duped, that he was genuine, and was really trying to do something good.” Dillon paused, and then added: “Or maybe I really misread him.”

Assante said he is also a “little less willing to condemn Rick … than some of the other guys,” calling Aviation Access Project “a good idea that was poorly managed and underfinanced.”

Meanwhile, he is among many—including Royster and fellow share purchasers, along with several others who declined to speak for the record—who have curtailed or ended their involvement in aviation.

“I sold my airplane to pay for the lawsuit,” Assante said.