Reconnaissance a key relief mission for GA pilots

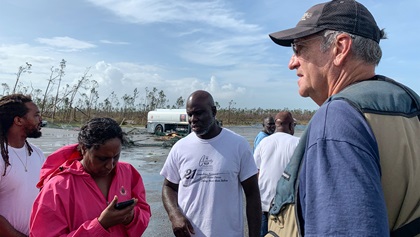

Gary Lickle has been flying general aviation airplanes into and out of the Bahamas since the 1970s, including relief flights after two recent hurricanes, but the devastation he saw from Hurricane Dorian went beyond past disasters, he said.

On Sept. 4, Lickle, 65, of Palm Beach, Florida, flew his piston-powered GippsAero Airvan 8 from North Palm Beach County Airport on a four-hour full reconnaissance of conditions in the Bahamas, taking hundreds of photographs of airports, homes, and public facilities below.

“This was way beyond anything we’ve experienced in Florida in our lifetime, let alone in the Bahamas,” he said.

Over the next few days his airplane, with its 2,000-pound useful load, moved many tons of supplies in and many people out of stricken areas, joining other GA aircraft in helping evacuate thousands of refugees to airports in Florida.

Organizations joining the mobilization of first movers included the Eagle’s Wings Foundation, and its Pathfinders Task Force Branch, which coordinates volunteers to deploy resources to stricken areas.

Paradise NGO, formerly known as the Paradise Foundation, focuses on working with a fleet of bush pilots to deliver relief supplies to the most inaccessible areas, as it did on Sept. 8 in the Bahamas. “Over the course of six hours, we loaded several planes and delivered over 12,000lbs of water, food, and supplies,” wrote Paradise NGO organizer Kent Anderson, describing the group’s Sept. 8 operations to Moore’s Island, off Great Abaco.

Lickle, a frequent vacationer in the islands, figures he has visited 300 of the 700 islands of the Bahamas.

A lawyer profiled for his commitment to conservation—he has given aerial tours of Florida’s Everglades to bolster interest in a foundation’s work to protect them—in 2015 and 2016 he delivered relief supplies by air to friends in Crooked Island and West End in the Bahamas after Hurricanes Joaquin and Matthew blew through.

But it was imagery of the “kill zone” and the swath carved by Hurricane Andrew, the Category 5 storm that struck in August 1992, that most vividly came to his mind as he surveyed Dorian’s destruction.

Whether acting as individuals or members of organizations, pilots scramble to assist after disaster strikes, and as Hurricane Dorian finally moved away from the Bahamas, many met the challenge.

“It’s a great time to be proud of your GA folks,” Lickle said in a Sept. 9 phone interview.

Commercial aviation deployed resources to help. Tropic Ocean Airways, a South Florida-based amphibious airline, announced that in partnership with Delta Air Lines, it had completed an evacuation mission in the Bahamas on Sept. 8, delivering relief aid and evacuating survivors. Delta’s McDonnell-Douglas MD–88 flew from Fort Lauderdale to hard-hit Marsh Harbour on Great Abaco, delivering 4,700 pounds of critical supplies.

“Once supplies were unloaded, the flight departed for Nassau with 72 evacuees,” the news release said.

In partnership with Blue Tide Marine and Global Empowerment Mission, Tropic Ocean Airways’ teams “rescued more than 150 people, conducted more than 120 rescue mission flights and transported 20+ tons of cargo including critical need items like water, food, generators, medical supplies, SAT phones, small airboats, and ATVs to aid in expediting rescue and medical efforts.”

“All of us were taking evacuees out,” Lickle said, noting that on a flight to Treasure Cay two days earlier, an “orderly, respectful” crowd had patiently waited for a chance to leave.

“There must have been a thousand people standing on the runway in 100-degree heat,” he said.

By Sept. 8, Lickle said, word was spreading among pilots that the islands “were sufficiently supplied for the week or two with food and water.” Sea and air relief efforts were moving into a new phase with the mission of delivering heavy equipment for debris removal and rotating first responders and medical personnel into and out of the most stricken areas.

More work to be done

When a hurricane or other natural disaster strikes, interest runs high among pilots as to how best to help. Lickle suggests early reconnaissance flights as one of the best ways GA can pitch in, pinpointing photographically the location and extent of damage and providing “real information” to counter what he said is the internet’s all-too-frequent proclivity to serve up misleading reports that can suppress or derail relief efforts.

With casualty estimates are still scarce and speculative, he said he expected that the death toll would be “going way up” from early reports, once there were “boots on the ground” in the hardest-hit places, especially shantytowns in the Abacos.

As recovery work continues, he said, GA pilots can still help deliver needed items that are filling up hangars and warehouses on the mainland, and should contact the nongovernmental organizations that are making arrangements to transport the goods.

“There are still plenty of opportunities to get the supplies out there,” he said.