As luck would have it

Airplanes let you know what they need, just like people. Flying the Sea Swan back to California from Washington for a planned supercharger upgrade was one of those moments where the airplane was speaking loud and clear.

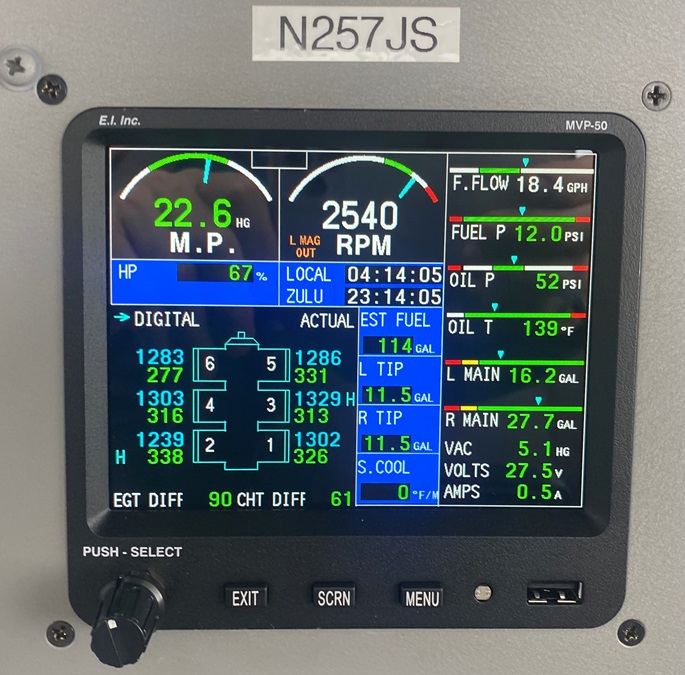

In solid instrument meteorological conditions (IMC), I got a red warning light and noticed the tachometer reading on the Electronics International MVP-50 was flashing at me and went from 2,550, which is a normal cruise setting, to more than 3,800 and back several times. This was clearly an indication issue as there was no change in the sound of the engine during the fluctuations. A few minutes later, all the engine information readings failed, which included engine temps, fuel and oil pressure, manifold pressure, and fuel quantity, to name a few. This was odd as solid-state equipment is typically “solid.” I knew something more had to be “up,” no pun intended.

As luck would have it, I had met Max Lyons, the owner of Hillsboro Aviation, just a couple months before when I flew to Orcas Island in the Citizen of the World. He had come up and asked about the polar circumnavigation and invited me to stop in sometime at Hillsboro Aviation, his FBO and repair station. I figured that the visit was long overdue and I could use a friend about now.

Lyons’ lead avionics guy Chris Brand had the cowling off in a short time and found that I had a fuel leak inside the cabin that was dripping avgas onto the control box for my MVP-50. Apparently, the leak had been present for quite some time. I would occasionally catch a smell of avgas in the cabin, but what airplane doesn’t smell a bit? The MVP-50 unit had been mounted with the connectors up instead of down as recommended by the manufacturer to prevent any moisture from flowing down the wires into the unit. To add insult to injury, my unit had been incorrectly positioned directly below a fuel connector and line that ran through the cabin, unbeknownst to me. The connector didn’t have fuel type thread sealer on it, so it leaked over time. As luck would have it, there was no fire and the unit had performed for over nine years in those conditions, which was probably a testament to its quality.

As luck would have it, the manufacturer's headquarters was just a 3.5-hour drive away in beautiful Bend, Oregon. Electronics International takes good care of its customers and staff members said if I dropped the unit off they would have it fixed by the time they had their third cup of coffee.

As luck would have it, the manufacturer's headquarters was just a 3.5-hour drive away in beautiful Bend, Oregon. Electronics International takes good care of its customers and staff members said if I dropped the unit off they would have it fixed by the time they had their third cup of coffee.

David Primmer, Electronics International’s sales and technical lead, showed me that the company’s new gold control boxes were now even more bulletproof and sealed, helping to protect the pilots from installation errors. The gold coating reduced interference and the display units were even higher resolution. Primmer gave me a brief tour of the facility and explained that all of the company’s gear was made in the United States. My sense was that after being in business for 42 years the firm was “solid” just like that MVP-50. Primmer also gave me a brief demonstration of the functionality of the unit, including bringing up some new display screens I had never seen, and showed me how to program in checklists. The display also comes in a round unit so it could be used in an existing hole in a panel and would not require any panel modifications.

While I waited for the team to clean the corrosion that shorted the unit off the circuit board, test the unit, reinstall it into one in a new sealed gold box, and program my display screen—as luck would have it, I realized I had a few friends at Epic Aircraft just across the Bend Municipal Airport. With little notice, I paid my friend Kathy Fosberg, the vice president of sales, a visit. She was so kind to give me a tour. I got to experience an airplane and not the mockup that travels around the United States to various airshows. Beautiful.

By midafternoon, I was driving back to Hillsboro Aviation and arrived to drop off the parts by 5 p.m. With a little overtime, the control box and display were installed and ready to go by the next morning.

My next stop was at Murray Field in Eureka, California. I had been flying in solid IMC since I had left Corporate Air Center at Skagit Regional Airport in Washington. I lined the Sea Swan up for a landing on the instrument approach. The touchdown was normal, but as I pushed the right rudder pedal to keep me lined up with the centerline the airplane started to lose rudder authority. I touched the right brake and my foot went to the floor. I had bled off some speed, but at this point I was along for the ride. The Sea Swan drifted to the left and off the runway onto the grass. It was all happening in slow motion.

The Sea Swan is a tough old bird (1977 vintage). Besides being half off the runway and tail feathers tucked between the floats the aircraft was fine. The airport looked quiet, but I chanced a call on the Unicom asking if anyone could offer assistance to an aircraft that had run off the runway. As luck would have it, the radio crackled to life and a short time later I was talking to Kyle Gabel from Northern Air, who helped me push the Sea Swan back onto the runway and eventually to a taxiway. Moments later, Austin Green, the lead mechanic with 40 years of experience, arrived and diagnosed the problem. The brake caliper had been weeping (I couldn’t see it); with hydraulic fluid pumped into the caliper, I was back on my way without any damage to the airplane in 45 minutes.

The Sea Swan is a tough old bird (1977 vintage). Besides being half off the runway and tail feathers tucked between the floats the aircraft was fine. The airport looked quiet, but I chanced a call on the Unicom asking if anyone could offer assistance to an aircraft that had run off the runway. As luck would have it, the radio crackled to life and a short time later I was talking to Kyle Gabel from Northern Air, who helped me push the Sea Swan back onto the runway and eventually to a taxiway. Moments later, Austin Green, the lead mechanic with 40 years of experience, arrived and diagnosed the problem. The brake caliper had been weeping (I couldn’t see it); with hydraulic fluid pumped into the caliper, I was back on my way without any damage to the airplane in 45 minutes.

The tech support staff members at Aerocet were awesome helping resolve the issue. I even got a follow up call later to check in and see if I was OK and if the problem had been resolved. Nice to know there are great people like this to help in time of need.

The rest of the trip went pretty smoothly and as luck would have it, the universe rewarded me with a beautiful God-inspired sunset after a total of eight hours of IMC during my total of 10 hours in the air. As I looked out the window, I couldn’t help but think that the backbone of aviation is all the great people I met along the way who helped me on my incredible journey. The trip was filled with many challenges but many synchronicities as well. There were clearly things that I was meant to learn along the way like the fact that we can’t do this thing called life or aviation on our own. That we must help each other and have faith that our journeys are inspired by more than chance or even luck. Certainly the Sea Swan was telling me what the airplane needed but I thought I also needed some time with my new friends sharing our passion of aviation.