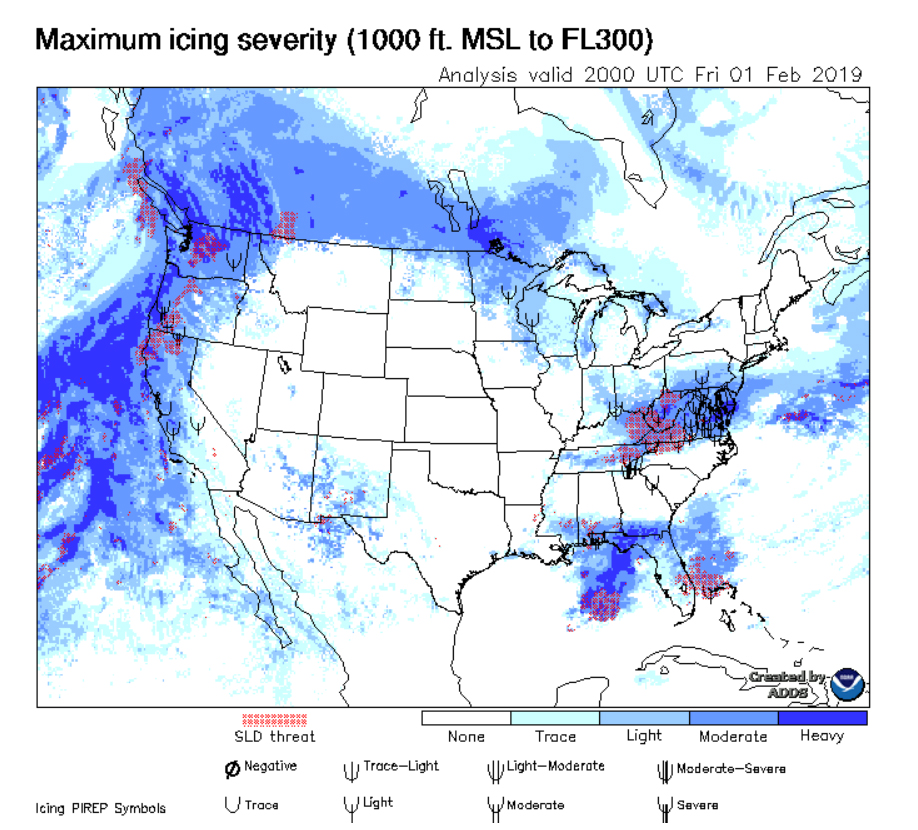

Avoiding precipitation and icing in flight is a process that begins on the ground. It’s good to use several sources of weather information to develop an accurate picture of current and forecast conditions. Use airmets, sigmets, and PIREPS, together with graphical depictions of current and forecast icing conditions to determine icing potential along your route and altitude.

CIP and FIP

NOAA’s Current Icing Product (CIP) and Forecast Icing Product (FIP) tools show both icing probability and severity at a glance.

CIP—This supplementary weather product provides a graphical view of the current icing environment. Using forecast model data for temperature, relative humidity, and liquid water content and drop size, it also includes observational data from METARs, NEXRAD, satellite, lightning, and pilot weather reports. Updated hourly and available about 20 minutes past each hour, the CIP provides current—not forecast—information as of the top of the most recent hour via icing severity graphics and icing probability graphics. All graphics display icing severity in five categories: none, trace, light, moderate, and heavy. Keep in mind that these icing severity levels are not specific to a type of aircraft or flight condition—they depict general icing conditions for situational awareness.

FIP—This tool examines numerical weather prediction model output to calculate the probability of in-flight aircraft icing conditions.

Note: If your aircraft is not certified for flight into known or forecast icing conditions, be especially cautious of areas displaying any type if icing severity, regardless of the probability indicated on CIP graphics.

Always have at least two good alternative plans to get out of unwanted situations.

Weather Sources

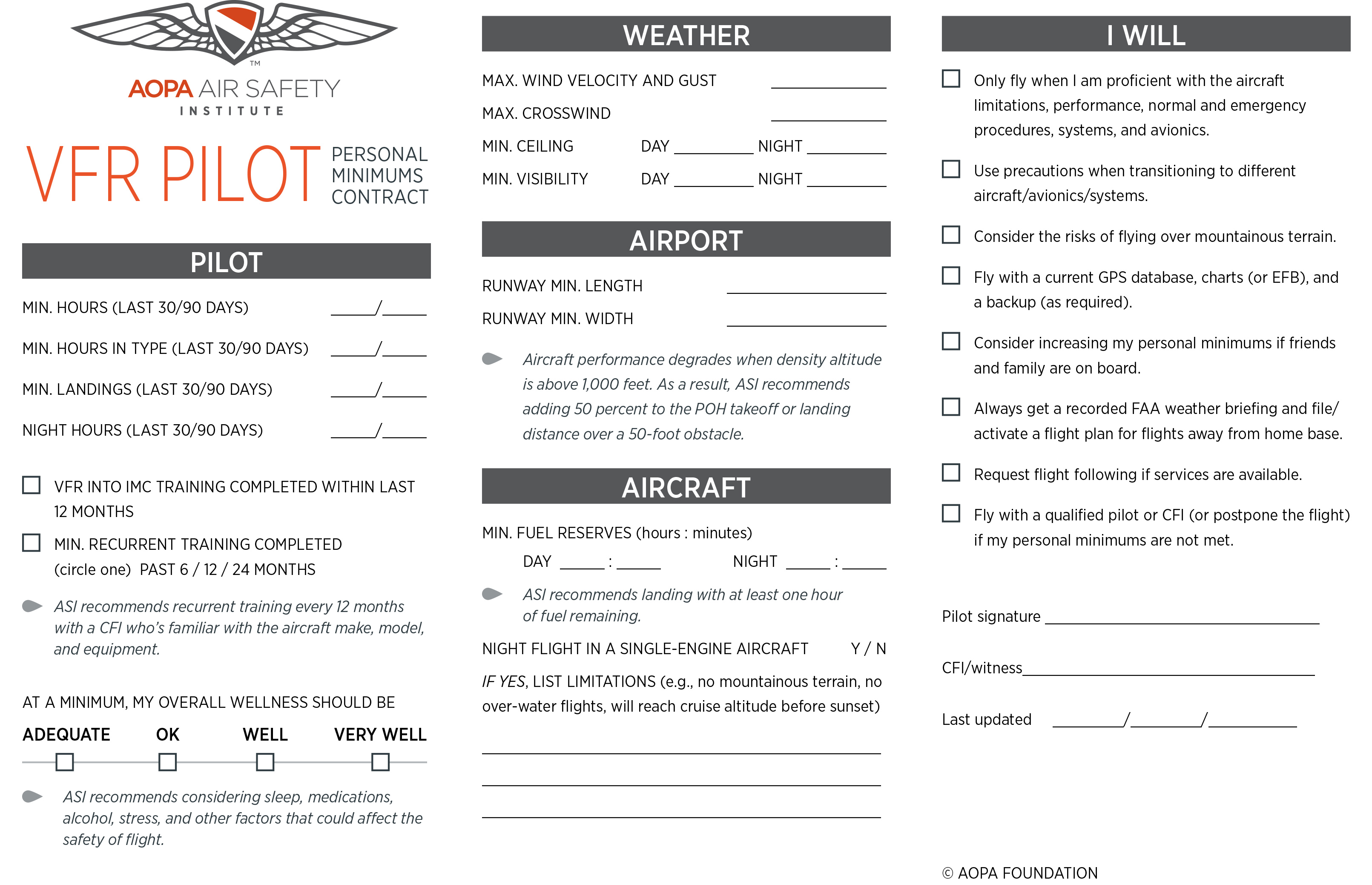

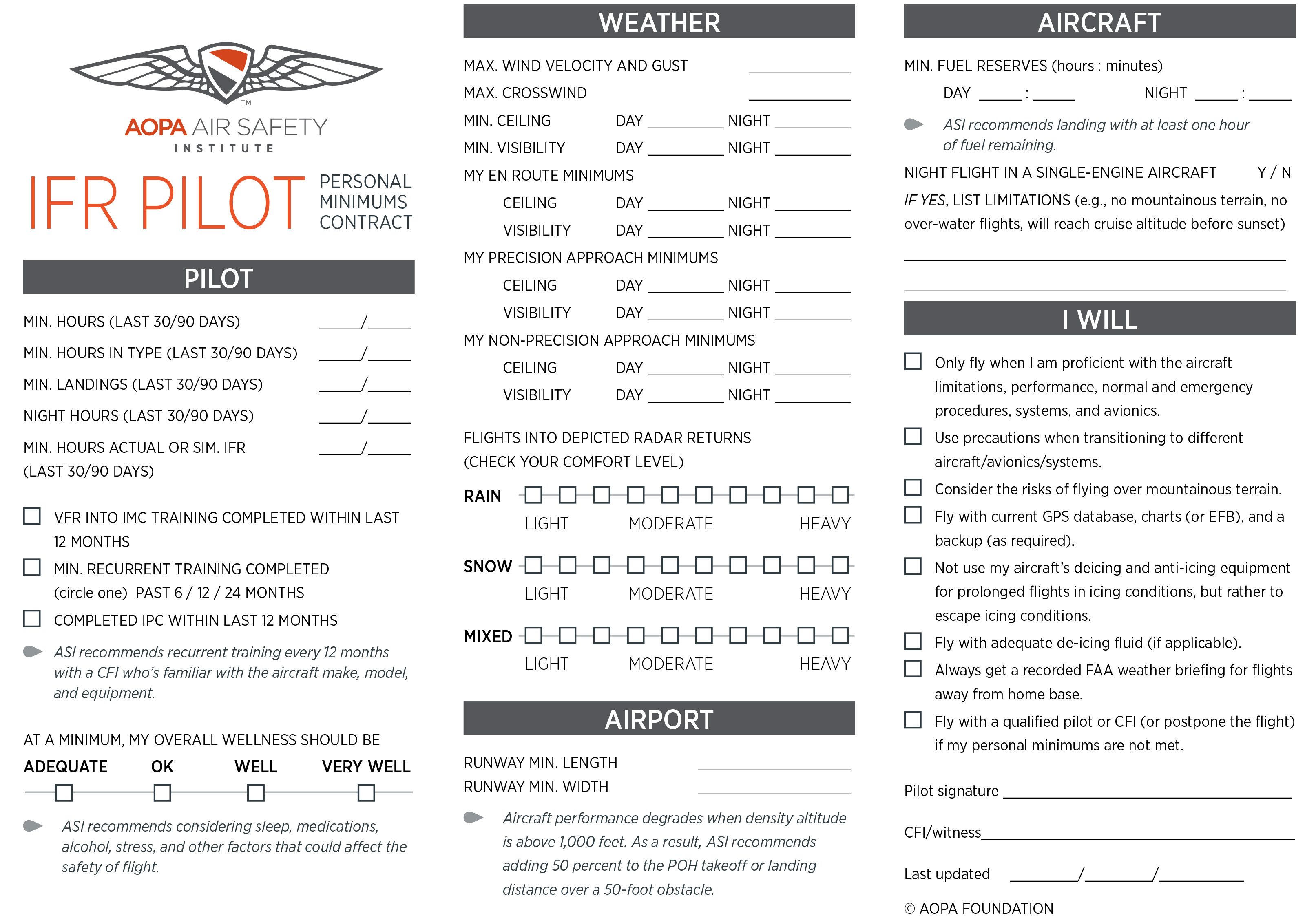

Personal Minimums

How to make the best go/no-go decisions? Develop personal minimums and write them down in advance of a flight, free of external pressure. Then consult your personal minimums before each flight to back up your go/no-go decision. This makes it easier to resist the temptation of “mentally negotiating” yourself into a tight spot during flight when influenced by emotion and hope of a successful outcome.

Personal minimums should cover minimum ceiling and visibility (day/night), maximum winds/crosswinds, minimum fuel reserves, pilot currency and proficiency, overall pilot wellness assessment, and aircraft/equipment limitations.

TIP: Update your personal minimums regularly to reflect current proficiency in the aircraft you fly.

Accident Case Study: Cross-Country Crisis

Experience the grim reality of an ill-fated VFR flight from Chicago to Raleigh, North Carolina. Cross-Country Crisis examines the pilot's flawed decisions as weather deteriorates and fuel becomes critical.Personal Minimums Contract

Download the AOPA Air Safety Institute’s VFR and IFR personal minimums contracts to develop your minimums.

Have a Plan B and a Plan C

In addition to adhering to personal minimums, always have at least two good alternative plans to get out of unwanted situations. These plans must include being prepared to divert and NOT make it to your destination. Before loading the aircraft, inform your passengers that a weather-related diversion is always a possibility.

Ask ATC: Weather Deviating

An air traffic controller explains how you can communicate your concerns about the weather and work with ATC to deviate from your assigned heading and altitude.

Aircraft Clean?

In addition to a normal, thorough preflight inspection, there are a few extra items to pay special attention to before departing for a flight where clouds and/or precipitation are likely to occur.

Pitot Heat—Without actually touching it, test the pitot heat by turning it on and feeling its heat near the palm of your hand. Use caution; some pitot tubes get hot very fast.

Drain Holes—Some aircraft have one or more small drain holes in the bottom of the fuselage to drain rainwater. If the airplane has been parked outside in cold, wet weather, ensure there isn’t a block of ice inside the fuselage and wings.

Aircraft Contamination—Frost, snow, and ice can accumulate on wings, elevators, and other surfaces when an aircraft is parked outside. Remove all frost, snow, and ice from the aircraft before departure. Any unremoved contamination will disrupt airflow over the wings and substantially alter flight characteristics, such as increased stall speeds, longer takeoff rolls, or even an inability to fly at all.

Preflight Factors

Let’s review the preflight factors for a flight conducted under visual flight rules (VFR) and a flight conducted under instrument flight rules (IFR).

| Considerations | VFR | IFR |

|---|---|---|

| Icing Risks | Flying VFR, icing in clouds will not be a factor. But precipitation and freezing rain are possible. | Flying IFR presents more icing risk factors than VFR. PIREPs are your best source of actual icing information. Treat all visible moisture as an icing hazard and watch the outside air temperature. |

| Locations of Fronts | Fronts often bring poor weather that may prevent VFR flight. Check conditions around the front, what kind of weather is behind it, and its forecast movement. | Fronts can bring temperature changes that create severe icing conditions. If crossing a front, it’s best to do so as quickly as possible. |

| Cloud Tops and Bases | METARs and TAFs report cloud bases as agl, while PIREPs report cloud bases and/or tops as msl. Graphical forecasts for the contiguous U.S. report tops and bases in msl. Area forecasts (FA) for Alaska, Hawaii, and the Caribbean report tops as msl, with non-msl bases or tops preceded by agl or CIG (ceiling). | Know where the clouds are (and are not). Escape plans should include an awareness of the nearest VFR weather. Also, depending on the cloud type, icing can be worse in cloud tops, so only climb if you’re sure you can climb over the tops. |

| Freezing Levels | The winds and temperature aloft forecast (FB Winds) provides freezing levels. Flying through light rain showers may be safe, but not if it’s freezing rain. Look for temperature inversions. Ice pellets at the current altitude are an indication that it is warmer above and there may be freezing rain nearby. | Check the forecast to determine where the freezing levels are expected to be along the route and compare this with the minimum IFR altitudes. Remember that structural icing may occur at temperatures slightly above freezing. |

| Terrain | Mountainous terrain further complicates the icing equation. Just as you are trying to get lower to get out of the unexpected ice, the ground may be rising rapidly to meet you. There also may not be many airports nearby for a quick escape. | Flying at or above the minimum IFR altitudes will provide safe clearance from terrain. If it’s not possible to stay out of icing conditions at the minimum en route altitude, canceling IFR to continue VFR under the clouds may be an option, provided you aren’t flying over mountainous terrain. |

Tip: Remember to write down the freezing levels before flight. You can compare them to the outside air temperature while en route. In addition, improve your situational awareness of freezing levels and icing potential by monitoring onboard datalink weather information.

Graphical Forecast

Graphical Forecast

The text area forecast for the contiguous U. S. has been replaced with the Graphical Forecast for Aviation (GFA) tool. This tool provides an excellent overview of expected cloud tops/bases/coverage, ceiling/visibility, precipitation/weather type, icing levels, etc.

Note: Text area forecasts are still available for Alaska, Hawaii, and the Caribbean.

How to make the best go/no-go decisions? Develop personal minimums and write them down in advance of a flight, free of external pressure.

Terrain Avoidance Plan

Obstacle altitude information is charted on VFR and IFR aeronautical charts—so use it! This is especially critical when you plan to fly at night or in low visibility.

- Stay above the charted maximum elevation figures

- Know your planned cruising altitudes

- Know your minimum safe cruising altitudes (for emergency planning)

- Have an exit strategy for unexpected weather/malfunctions

Rules of Thumb

Use these formulas for quick estimates.

-

Cloud Bases

Temp (F) - Dew Point (F) / 4.4 x 1000

For example, if the temperature at the surface is 65 F and the dew point is 40 F, the cloud bases should be at about 5,600 feet agl (65 - 40 = 25/4.4 = 5.68 x 1,000 = 5,680).Or

Temp (F) - Dew Point (F) x 2 and add two zeros

For example, if the temperature at the surface is 59 F and the dew point is 57 F, the cloud bases should be at about 4,000 feet agl (59 - 57 = 2 x 2 = 4 and add two zeros = 400). -

Celsius to Fahrenheit

Double the temperature and add 30.

For example, 20 degrees Celsius is close to 79 degrees Fahrenheit (20 + 20 + 30 = 70).

The most accurate formula requires more thought: (Celsius x 9/5) + 32 = Fahrenheit

A garden sprayer can be used to help remove frost.

A garden sprayer can be used to help remove frost.

“Hangar-in-a-can” products are small enough to fit in a flight bag.

“Hangar-in-a-can” products are small enough to fit in a flight bag.